The Career of Chaw A Hjong is a short story written by László Székely, a Hungarian planter working in Deli in the 1920s. This is one of the few stories written by European on the life of a Chinese Coolie in Deli. László mainly described the idiosyncrasy of a Chinese worker, who happened to be lucky. The same style of story is also found in his description of a Chinese foreman or tandil, Lim Ah Yung.

A new assistant just arrived at the plantation. He was a sinkeh, a novice in the equator, who, unlike his predecessor, who had long been exhausted after ten years of service in the jungle under the cutthroat tropical sun, still felt young and energetic. The brand new young assistant was bubbling with new energy brought from Europe. It would not be long before this effervescent energy would also fade under the tropical heat and gradually give way to languid, indifferent laziness. But for now, the new assistant was still enthusiastic, and that would leave the coolies, accustomed to the lazy mentality of the previous assistant, always in for many unpleasant surprises. Above all, the new assistant demanded obedience and assumed that the coolies would follow.

On the afternoon of the first payday, he snapped at the astonished coolies, who, accustomed to freer manners, came to the payout bare-chested. ‘What are you doing to me, you dirty crooks. How do you envision showing up naked for the payoff afternoon?” The stern assistant bellowed. “I’ll start paying in five minutes. Anyone who dares to appear without a sarong will not receive his money. ‘ The coolies looked at each other in bewilderment. Most of them didn’t even have a sarong, and the few who did had one left it in the coolie barracks, too far away to pick up, at least a quarter of an hour’s walk from the assistant house. The hard-hearted tuan had said he would start paying in five minutes, and those who do not wear sarong or are not present would receive no wages.

That was when Chaw A Hjong’s career began. Chaw A Hjong did wear a sarong. It was a worn-out sarong, consisting of two dirty pieces of white cloth patched together, but it was a sarong. Suddenly, the resourceful Chaw A Hjong came up with a genius idea. “Anyone can borrow my sarong for ten cents,” he said to his desperate colleagues. ‘Let us stand behind this bamboo fence, and when the tuan calls out the name of one of us, he quickly puts on the sarong, goes to the tuan, gets his wages, comes back quickly, takes off the sarong again and then the next is turn. Well, what do you think? ‘ The coolies were indignant; ten cents was way too much. But when the five minutes were up, the tuan immediately called out the first name. Lim Kui Seng!

He was bare-chested and stood in front of the tuan’s table. He took his wages – one Singapore dollar and seventy-four cents – and disappeared again behind the bamboo fence. He returned the sarong to Chaw A Hjong and paid ten cents. The next forty-eight did exactly the same. With proud steps and with forty-nine dimes plus his own pay – one dollar and eighty-nine cents – tied to the tip of his sleeping pants, Chaw A Hjong walked home to the coolie barracks, a cheerful grin on his yellow face.

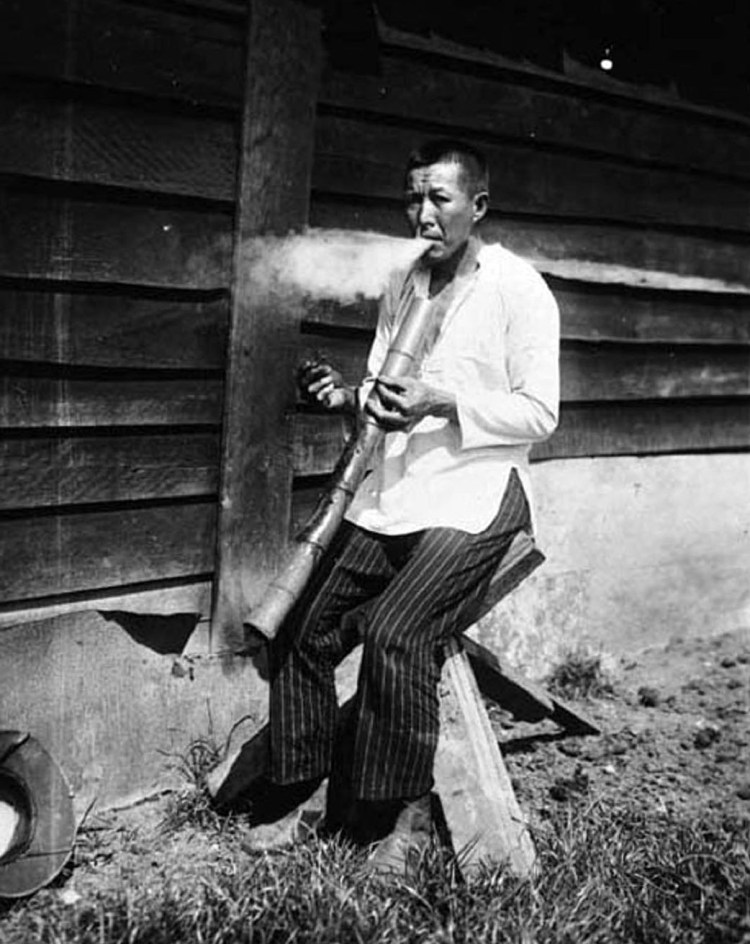

“Money makes money,” thought Chaw A Hjong. He was just a coolie. He had recently come from China, where he lived with hundreds of thousands of fellow animals – like animals in human form – in a neighbourhood of packed boats and boats. Occasionally he had a job; then, he trotted for a day sweating and panting for a rickshaw. In a run, he drew on countrymen born under a happier star as well as the rulers of the world, the whites. At the end of the day, he returned the rickshaw to its owner, counted ninety percent of his earnings as rent, and, with the few pennies left, crawled back to his twisty, maze-like neighbourhood; or he would sit on a street corner begging, his wounded feet sticking out.

Now there was six dollars and seventy-nine cents tied to the tip of his sleeping pants! In Chaw A Hjong, the entrepreneurial spirit of his race suddenly awoke. You can do a lot with six dollars and seventy-nine cents. You can spend it, you can buy opium for it, you can hang out with a few cheap, greedy Malay hookers, but you can also start a business with it.

Chaw A Hjong went to the Chinese kedeh, walked into a shop and bought two iron pans for two dollars, ten cents ginger, fifty cents dried fish, twenty cents lombok peppers, two dollars and twenty cents a fat piece of pork. The Chinese butcher, for twenty-five cents soy sauce and fifty cents noodles. Then he sat down between the coolie barracks and waited. In front of those barracks, the coolies and a few orang kontrak from an adjacent company sat dice on the floor. The dice rolled happily, and the winners expressed their cheerfulness in a loud voice; the losers hissed discontent after every failed throw; a breath of wind flared up the little oil lamps and cast a flickering shadow on the yellow sand.

Chaw A Hjong had set up his occasional kitchen near the players: he had made tripods under the pans. He cut the fatty pork into the pan, poured the spices on it and started cooking like that. A lovely scent quickly spread through the hot air, mingling with the scent of the sweating coolies. More and more often, a winner got up and sniffed in the direction of Chaw A Hjong’s improvised kitchen. Money quickly won also rolls quickly. The winners did not give up, they ordered generous amounts of juicy fatty meat with ginger, fish fried in coconut oil or a portion of noodles. They quickly worked the dishes in and excitedly hurried back to the dice players to resume their place around the dice mat.

When Chaw A Hjong counted his money the next day, he had eleven dollars and twelve cents plus two pans and a quarter of the soy sauce; he even had a little meat and a tiny bit of dried fish left. Then Chaw A Hjong thought long and hard.

It was hari besar – payday. The dice players disappeared for a few hours to rest. Chaw A Hjong retired to his room, where he sat for a long time brooding. After an hour and a half of worry, he went to the butcher and bought five kilos of meat; he bought herbs from the vendor and then returned to the barracks. The dice players were again on the mats and let the dice roll. They kept playing until the next morning. Then they picked up their shovel and axe and left for the mining. None of them had any money anymore. But Chaw A Hjong had twenty four dollars and forty two cents in a tin box. He buried the box by the riverbank under a large rock and left it there until the next payday.

In the meantime, money was not out of his mind and Chaw A Hjong continued to make plans.

Fourteen days later, on the day of the next payout, he shuffled home from work, lost in thought. He worried about how to expand his business without handing over some of the profits to anyone. Exhausted, the heavy shovel on his shoulder, he dragged himself with difficulty. He felt dizzy and his stomach rattled with hunger, as Chaw A Hjong denied himself as much food as possible to achieve his goal faster. A Javanese coolie woman trudged ahead of him, she too came from work. His wandering gaze rested on the woman walking in front of him with weary, limping steps. He quickened his pace until they walked side by side.

Chaw A Hjong was young. He did not know exactly how old, but he was still young and healthy. Ju-Imah was old, shrivelled and worn out. Even the Malay coolies no longer wanted her, even though there were very few women and very many men on the venture. When they reached the coolie barracks, they had reached an agreement. That same evening, Ju-Imah moved in with Chaw A Hjong. She took her things from the Javanese barracks: a tie-dyed sarong, a rust-stained tin teapot, a worn-out mat and a broken mirror no bigger than a palm; so she moved into Chaw A Hjong’s room. Ju-Imah knew that by this step she was irrevocably turned away from her own kind and that her countrymen, who worshipped another god, spoke a different language and ate different dishes, would cast her out. But she was aware that she was old and that she would not be able to keep up with the coolie work for long. Moreover, the Chinese had more respect for women than the men of their own people. On the evening of the following payday, the two of them were already running the business. She cooked and Chaw A Hjong brought the fragrant dishes in beautiful green banana leaves to the customers.

The business flourished, and Chaw A Hjong continued to expand it. Not only did he sell fried meat and fish, but he also made loans. Players who had lost their last cent in the dice and were in a tight spot turned to Chaw A Hjong for a small loan. Chaw A Hjong always agreed but gave no more than one dollar, which was to be paid back at fifty percent interest at the next payout. The debts were always paid punctually, for in business, the word of a Chinese is as sacred as for us the honour of an officer. Coolies can ruthlessly rob each other, even from a robbery, they do not shrink back, but borrowed money is always paid back right on time with the interest. Borrowing money is a financial transaction and, therefore, a matter of honour. Chaw A Hjong never made a loss on borrowing money, except once, but that was at the beginning of his career as a banker, when he did not yet have sufficient experience. He had lent five dollars to a coolie because he trusted that coolie would recover his lost money. However, the coolie was chased by an accident and also lost the five dollars borrowed. At the next payout, the debtor could only pay back two dollars and twenty cents and thus could not pay off his debt. He hanged himself out of shame. Chaw A Hjong, of course, was of no use to that; he had lost that five dollars forever. From this, he drew his conclusion and from now on, he did not lend more than one dollar to anyone.

Gradually everyone became indebted to him. Yet Chaw A Hjong never wrote down the name of the debtor or the amount borrowed. The entire bookkeeping was stored in his head: every sum, item, bill, interest and expiration. Chaw A Hjong was never mistaken. Thus he became a rich and important man. He no longer kept his money in tin boxes, but bought gold coins that he hung on the side-made bath of Ju-Imah. When he had so many gold coins that they could no longer be hung on Ju-Imah’s clothes, he had to find a reliable investment. He was lucky again: the head-to-the-tooth, which, with the help of his inscrutable power and mysterious practices, held all the coolies under his control, needed money.

The head tandil, Chaw A Hjong listened reverently to the krani conveying the message of the great taukeh, for it was far from the point where Lim A Bak, the High Chinese, personally would turn to an ordinary coolie. With quick and deep bowing, wringing his hands, Chaw A Hjong thanked in a long speech for the trust that the head tandil placed in him, the great taukeh did him, good-for-nothing and wretched coolie, with that a great honour and thereby raised him to his own height. Chaw A Hjong’s long-winded speech was laced with courtesy words, but as he spoke these last words, the krani waved a defensive hand as if to indicate, “The great taukeh has honored you, but raised it to himself … no, that is an exaggeration to say the least. ‘ At that point, Chaw A Hjong lit up and he continued his speech in a different way. ‘Krani, I have five hundred dollars. Tell the great taukeh that this amount, which includes all my earthly possessions, is at his disposal. At the end of the month, the head tandil will honour me and give me back seven hundred and fifty dollars. ‘ The Krani nodded his head back – “Of course. You will bring him the money today. ‘ With these words the Krani turned and walked away.

Chaw A Hjong took the gold coins – all but three – from Ju-Imah’s chest and brought them to the head tandil’s house the same evening.

From that moment on, Chaw A Hjong’s career gained momentum. At the end of the month, the head tandil paid him back seven hundred and fifty dollars, and at the beginning of the following month he asked to borrow another seven hundred and fifty dollars. Another month later, he paid back $ 1,100 and then invited Chaw A Hjong to a game of dice. Chaw A Hjong became terrified of this great honour, his knees trembling. He put on his newest addition: a beautiful white suit with orange shoes. With trembling knees and walking unhappily, because he was wearing shoes for the first time, he hurried to the house of the great taukeh. The pot-bellied gentlemen with their long nails were already together and were fanatically playing dice. Chaw A Hjong very courteous and cordial and generously offered him a drink of toddy. Then he invited him to take a seat at the table and kindly urged him to take part in the game. Chaw A Hjong had never drunk liquor before and took a die for the first time. Suddenly he was now sitting among the arrogant big taukehs, and his eyes were dizzy: at the sight of a large amount of money it was shimmering before his eyes. He knew that playing dice could make a person lose his mind: of all things he owed his fortune to coolies obsessed with the game. But now he dismissed his hesitations. He was filled with pride to play the honour that came to him with the taukehs. He reached into the pocket of his white linen suit and put in a hundred-dollar bill.

The next morning he had won eleven thousand four hundred dollars. His ears were ringing, utterly exhausted, he stumbled home to the coolie barracks, after leaving the money in the custody of the main tandil. Obviously, he had not received a receipt, that was not necessary: it was conceivable that someone who was unprotected would be drunk and robbed of his money when playing dice, in fact, no one would disapprove of that, but depositing money with someone was quite another: it was a business. Then it was the merchant’s honour. And in that case, the word given was a guarantee that no one would dare to touch the deposited money.

The head tandil tore the thin gray hair from the head in anger. Chaw A Hjong stumbled home to the barracks, woke Ju-Imah, took the remaining three gold coins from her, took off her bathing suit and her floral-patterned sarong, and chased her out of the house. Then he took his heavy shovel and went to work on the exploitation.

From here, it is tough to follow Chaw A Hjong’s career. His contract expired a few months later and Chaw A Hjong disappeared from the plantation. Then he turned up in the city, where he managed various mysterious cases. His junks with their bat-wing sails sailed the whole world from the thousand islands. Sometimes they popped up here, sometimes there, but always at night, under cover of darkness, in a dark, muddy, mangrove-lined bay. Chinese, who looked like pirates, quickly got rid of the suspect and disappeared into the dense, warm fog.

Chaw A Hjong rose enormously in reputation: his countrymen feared him, and the Europeans also had to reckon with his mysterious power. His palace was accessible, or rather inaccessible, through three gardens with dragon-adorned gates, for huge, gruff bodyguards – who looked like executioners – kept no unwanted guests from entering.

One day, the disaster still happened unexpectedly. Chaw A Hjong, escorted by his bodyguards, came out of the decorated gate to get into a rickshaw waiting for him there. Suddenly, an old beggar, squatting in front of the gate, stretched out her long wrinkled arm. Something gleamed in the sun, the great taukeh grabbed his stomach and collapsed.

The wise gentlemen of the court could not figure out what had moved the old, stubbornly silent beggar to murder the wealthy Chinese, who was so highly regarded and known for his generosity. Of course, no one remembered that Chaw A Hjong had started his career as a coolie. No one could remember Ju-Imah either. After all, time passes very quickly at the equator.

(This story by László Székely originally appeared in the Hungarian newspaper Pesti Napló on November 9, 1937, and was first translated into Dutch by Gábor Pusztai). https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_ind004199501_01/_ind004199501_01_0026.php

Leave a comment