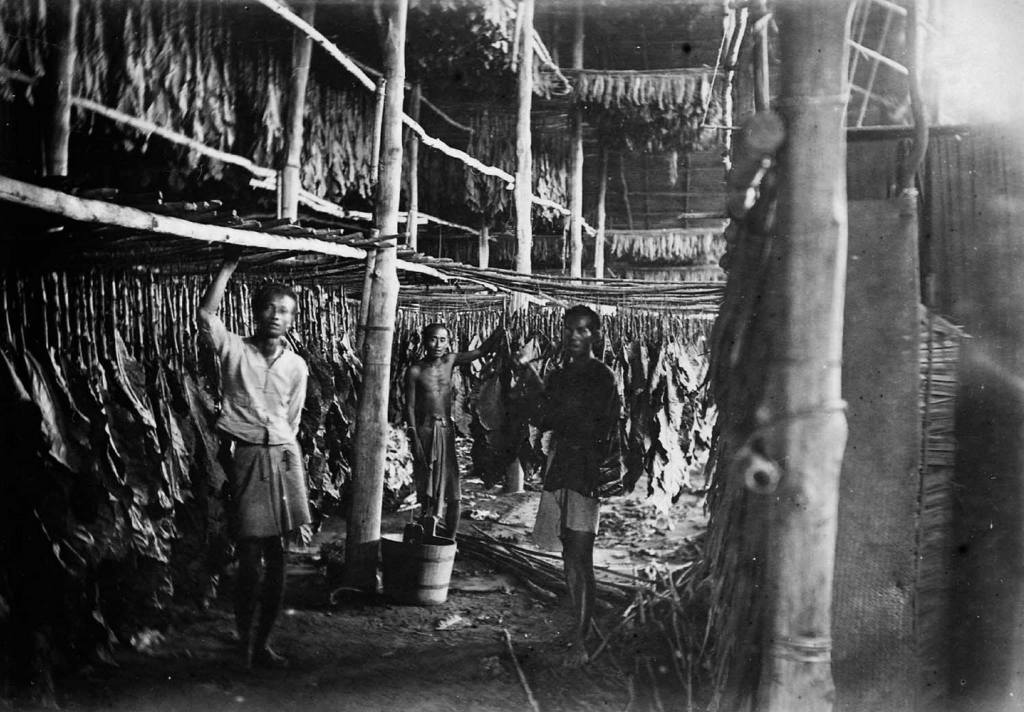

Dixon, 1913

Anyone who only knows the Chinese as a merchant, the always polite, stereotypical smiling baba, is completely strange to the Chinese field coolie on Deli. The former was born in Indonesia (baba), has acquired a superficial courtesy through his long association with the European and through his trade relations, but the latter, imported from the interior of China as a coolie for a Deli agricultural enterprise, is of quite a different woodcut.

Not all who come to Sumatra’s East coast in this way belong to one and the same tribe. Completely different from each other are the Haihongs, Lokhongs, commonly called on Deli Hailokhongs, the Tiotjoes, Kehs and Macaus. Both in appearance and in nature and character, as a result of which bloody fights between and those tribes often take place at the companies, they also differ in their own language, so that they can sometimes hardly understand each other.

A Hailokhong is noisy, tempered and short-tempered; a Keh and a Macau are calmer and more tolerant, though more likely to covertly kill or plan someone they hate.

The Hailokhong, generally considered the best farmer, are stronger, better able to do hard work than the other tribes, who, on the contrary, do their job more carefully and neatly, though a little slower.

All without distinction, however, have in common some traits of character, the chief of which is their sense of justice.

The first Malay word known by “singkeh Chinese” is “Patoet” (righteous).

“Taukeh patoet loh” (boss is decent) in their broken Chinese-Malay the greatest praise for a European.

When a Chinese coolie is convinced that he is being treated “patoet” at a company, he feels more “happy” and likes to work there.

A second trait, also very much developed in them, is the desire to make money, which distinguishes them from most Eastern races.

A Javanese will not care much whether he already earns a few cents a day by working a little harder or longer. He is satisfied when he has enough to live on and can buy a new sarong or badjoe on festive occasions.

The Chinese coolie is out to earn as much as possible, likes to do more work for more money.

This character is very beneficial to the planter.

Tobacco culture demands daily meticulous care, to which other Oriental races, because of their innate indolence, do less well, even if they are paid as well as the Chinese. This is perfect for the tobacco culture, which demands a lot from the physics of the man.

Strong, tough, handy, sober, with love for the culture, because he knows – especially with the latter in mind – that the better the tobacco grows, the better he delivers it, the more money he will have at the end of gets hold of the harvest year. He is the designated man to plant tobacco.

Without the indispensable Chinese coolies, the tobacco culture on the east coast of Sumatra would certainly not be at the height at which it is now.

Before daybreak, the Chinese field coolie is already outside to take care of its young tobacco, to water the seedbeds, to look for caterpillars of its tobacco, or to prepare the land for planting.

He is at work until after sunset, with only a few hours of rest in the afternoon. It is also not uncommon for the coolies to be busy in their tobacco on bright moon evenings, long after normal working hours, after a hard day’s work. A Chinese may not be a sympathetic workman because of his loud and noisy behaviour, but every planter must have respect for his tremendous power and performance.

No race in the world, then, would be able to do such gruelling and versatile work in a subtropical climate.

In Deli, however, there is tobacco here and there with Javanese planted, even one of the largest companies has turned to one of its companies to employ Javanese “exclusively” for culture.

Time and again, attempts have been made to replace the more expensive Chinese by other labor. Still, whatever results have been achieved with this, or however such experiments have turned out, they had only proceeded to do so when there was a temporary shortage of Chinese labor, or when it was feared, that the ever-flowing stream of Chinese immigration might dry up.

However, the practice has shown that the Chinese remain the right man for the culture, which cannot be replaced by others in the long run.

Nowadays, in Deli, one often hears the complaint that the Chinese coolies in earlier years did more themselves and needed less help with their work than they do now, then one should not forget that the way in which the culture is driven has evolved. Years have significantly changed; that due to the faster planting nowadays, the harvesting must also go so much quicker, so that the Chinese are not able to do all the work themselves, as before.

In addition to both of the above properties, a sense of justice and for making money, which does not mean to say that a Chinese is always just as thrifty, he also has many bad character traits like every human being.

Without entering into a psychological study of the Mongol race, we will consider only those peculiarities that a planter at Deli has to deal with almost on a daily basis at work

From: Dixon, C.J., 1913. De assistent in Deli: practische opmerkingen met betrekking tot den omgang met koelies. JH de Bussy.

Leave a comment