Ann Stoler on the 1929 murder

In November 1929, the murder of Assistant Landzaat’s wife by the coolie Salim on the Parnabolon estate set loose the few repressive mechanisms that had been held in check up until then. The muted panic of the preceding months crescendoed into an Indies-wide scandal; 167 European women in Deli sent telegrams to Queen Wilhelmina demanding protection (OvSI 1930:44; Said 1977:164).

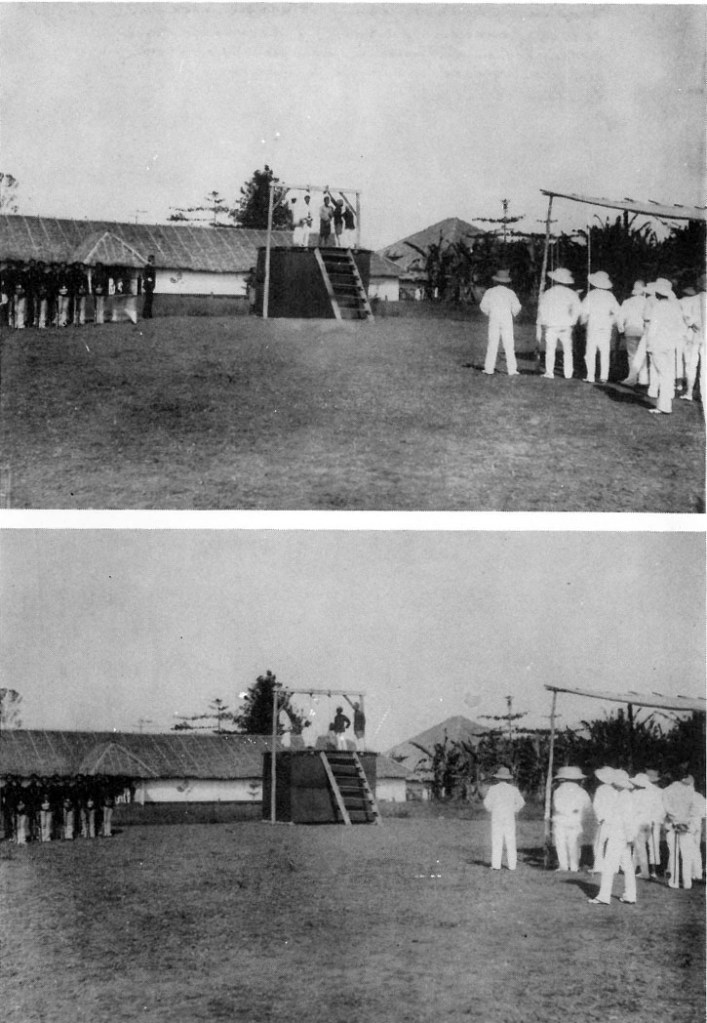

And while newpapers in java speculated on a “Moscow-Deli connection,” army troops were sent by the governor general in Java to “restore order.” Within a week of the incident Salim’s trial started, five days later he was sentenced, and on October 23 he was scheduled to hang. From the court proceedings (published in the native and European press) it seems that Salim had been transferred to an estate division far from where his wife was living. For days he petitioned to the head foreman and to Assistant Landzaat to have his wife transferred as well, but the request was denied supposedly because she was already pregnant by another man. Salim told the office clerk that he would not work until the issue was settled. In the meantime, Landzaat, angry with Salim for making trouble, threatened to have him punished by the police. Three days later, when Salim’s wife still had not shown up, he approached Landzaat’s house and, finding him not at home, stabbed the assistant’s wife to death. Other versions of the story were also circulated.

According to Hasan Noel Arifin, editor of Pewarta Deli (who went to Parnabolan to investigate the situation more thoroughly), Landzaat had decided to take Salim’s wife as his own mistress and would not allow her to be transferred to Salim’s division. This did not come out in the trial; at the hearings, the foreman testified that Salim’s wife had not wanted to return to him, although she was not in fact pregnant.

Pewarta Deli [24 July 1929] was not satisfied with the testimonies. As with numerous other coolie trials, Salim could not argue his own case or give voice to the more general situation surrounding the incident. The paper proceeded to ask questions the court ignored.

The prosecution, of course, asked Salim whether he read communist newspapers and belonged to a communist organization. It did not ask why Landzaat was so easily enraged by Salim’s behavior, or why the head foreman had already kicked out two other coolies [before Salim arrived) at the new division. These turned out to be not unimportant questions.

Parnabolan’s administrator was quietly dismissed after the trial when it was found that there had been repeated incidents of maltreatment and general labor unrest on the estate.

The fact that Pewarta Deli refused to treat the Parnabolon affair as anything more than what might be expected from an unjust labor system, was met with sharp disapproval by the European community, which was milking the incident dry for its own purposes. At the end of July a secret circular was sent to all the Deli trading houses requesting that they withdraw advertisement from Pewarta Deli because of its reportedly cavalier attitude to Mevrouw Landzaat’s murder. Soon after, another meeting was held at which it was decided to boycott not only Pewarta Deli but “all anti-European publications in the Melayu press.” Three days later, Pewarta Deli’s editor was brought in for questioning by the police and the newspaper was temporarily shut down. The crackdown was well on its way. Kusumasumantri, who had in earlier months been subject to several interrogations by police intelligence, was finally arrested, this time on the pretext that he had participated in communist activities six years earlier! [OvSI 1930:33).

Although the Chief Head of justice publicly affirmed that the Parnabolan murder was unrelated to extremist activities, this did not deter planters and politicians from using the case as a raison d’etre for further repression of civil rights.

Only two months after the Parnabolon incident, the manager of the Aloer Gading estate was assaulted by 20 coolies and murdered. Five workers, including a foreman, were brought to trial. In contrast to Salim’s hearing, the witnesses’ testimonies were far more revealing of the violent context in which the assault had taken place. According to the accused, the incident had been precipitated by the demotion of a foreman whose “gentle manner” vis-a-vis his workers had been considered inappropriate by the manager, Waller.

In the trial, the new foreman, who was also implicated in the murder, testified that only those persons willing [and unafraid) Ia beat coolies were promoted to a supervisory position. Other workers testified to severe beatings and abuse by Waller, who had increased the work load as well as the frequency of corporal punishment since becoming manager. Even with this evidence of “extenuating circumstances,” the political climate in Deli was such that the court remained unsympathetic to the workers’ case.

In October 1929, four workers were sentenced to hang, and one was given a fifteen-year prison sentence. But as in the Parnabolan incident, no connection was found to extremist agitation.

From: Ann Stoler. Capitalism and Confrontation in Sumatra’s Plantation Belt.

Leave a comment