Gorton Angier, 1908

A few words may be devoted to another district amongst the many rich islands comprised in Netherlands India. Foreigners as well as Dutchmen are interested in tobacco estates on the east side of Sumatra. Deli is the chief district, and is reached in a night’s steamer run from Penang to the port of Belawan. The bulk of the tobacco is shipped from there via Penang for Europe, but Singapore and Sabang (Pulo Way) also participate.

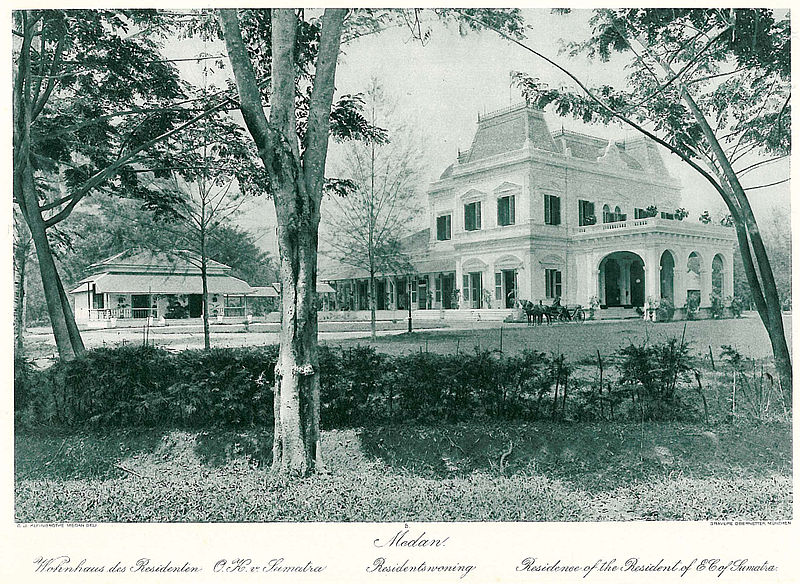

Belawan is not prepossessing, but it has worked off some of its bad name as a fever-stricken spot. The wharves, that were badly wanted on the occasion of a previous visit, have been constructed. Soon after arrival, a somewhat leisurely train on the Deli Spoor takes you to Medan. There commercially, and in banking ways, business much the same, with a slight addition to its volume. Chinese tokos (shops) are improved, and successive fires seem to have been of some assistance to this change. Any way, an advance is to be seen. The town maintains its characteristic cleanly and neat appearance, and might well be taken as a model for places not far distant which have greater pretensions. It looks well-groomed, and is lighted by electricity on all the roads and thoroughfares. A notable recent building is that of the club, with its really fine theatre.

This, like many other improvements, is largely due to the enterprise and generosity of the Head Administrator of the Deli Maatschappij. This company, with its magnificent administration buildings occupying a great terrain in Medan, is the leading factor in the place. Medan bears the impress of what may be achieved if the head of the great company is concerned to assist in the public interest. The Java Bank was about to open a branch, with the object chiefly of inaugurating the guilder as the currency, in lieu of the Straits Settlements dollar, which, whether Mexican, British, or Straits, had hitherto prevailed. Attempts have been made from time to time to introduce the guilder, but because of the necessity of regulating the bulk of its payments in Penang, where the trade of Medan is largely centred, and of paying the coolie in a coin he knew, they had not hitherto been successful.

As long as there was the advantage that accrued in dealing in silver with Penang instead of in gold with Batavia, the planting interest was always against the guilder. Now that the Straits is equally on a gold standard with Netherlands India, the change has been brought about. (The guilder was already the currency at Pankalan Brandan, the centre of working of the Royal Dutch Petroleum Company.) The Penang trade will flow as before, but will be adjusted on a gold basis instead of on a silver basis. The danger from the Government point of view, one that may equally be brought on the community, is that arising from the smuggling of spurious guilders.

That coin contains only 53 per cent, of silver, and the white metal will have to rise very considerably before the profit attaching to making guilders, of quite as good fineness as the Government coins, will disappear. The facility with which spurious coins could be introduced by every class of craft will be evident from a glance at a map of the coast line. It is certainly one that must always be borne in mind.

The actual cultivation of tobacco remains on very similar lines to that followed for some years past, but improvements in manures, in treating the bibits, in detecting worms, and in other ways, are constantly the source of experiment and research. As far as the manner of cultivation, from the payment of the coolie upwards, is concerned, probably no better method could be pursued than that in force on a tobacco estate. It provides an excellent profit-sharing system. From the coolie to the assistant, the estate manager, and head administrator, and from him to the proprietor or shareholder, each does relatively as the crop grows and sells well or ill. Each has his own interest, which is identical and in common i.e., to produce the leaf as well and as cheaply as possible. Dutch law has been in the past favourable to easy working. The coolie regulations were fair, and made it possible for the man to earn money, while the planter had not the same restrictions that were imposed on him under the British flag say, in the Federated Malay States. The result was satisfactory all round, and conduced to the advancement of the tobacco industry.

Now the conditions are not so easy, and the planter is hedged about with many more formalities, and harassed by the necessity of useless returns. Estate managers and administrators who were known to look well after their men were not bothered too much by officialism, and the trouble saved all round by the system was considerable. Many wish that those conditions still prevailed, but the planter has now much more to contend with. Nor does the Government omit to exact taxation from estates, and also of an individual or personal nature. These taxes have not hitherto been excessive, perhaps ; at least, they would not be were an equivalent given for the money gathered. A certain amount of police protection is, of course, forthcoming in the event of its being required, but as to making roads, or such like works, the Government does not act up to its obligations. The planters provide the bulk of the revenue and are entitled to have more done for them.

The Far East revisited; essays on political, commercial, social, and general conditions in Malaya, China, Korea and Japan. 1908. Gorton Angier

Leave a comment