Boersma, 1870-1920

In response to the frequent complaint, the English committee had carried out its investigation in 1876, and in 1877 a “Chinese Protectorate” was established: a European official in Singapore and an assistant in Penang, who supervised the recruitment.

Depots were set up for the enlisted people, and each coolie signed the contract for the protector, who questioned him beforehand. The protectors were further supervised over the businesses in the Straits and over the treatment of the coolies.

Henceforth the Government allowed recruitment only to those who had received a permit. However, the usefulness of this Chinese protectorate, this labor inspectorate, for Malacca itself is disregarded. The doctors of Deli recognized the good side of the institution. For them, in addition to the evil of the coolie-exploiting brokers, the evil of the coolie-protecting came the inspectorate.

Henceforth the coolies for Deli concluded their contracts with the protector, and if he refused, the contract was not made.

And with that, the protector already threatened in Singapore, because the Deli planters sent back weak, almost useless coolies. The institution of a medical examination prior to the conclusion of the contract brought the dispute to an end. Still, the British Government continued to demand that the planters also recognize and accept the contracts concluded for the protector.

The Deli Planters Committee, chaired by J. T. Cremer addressed a memorandum of defense to the consul-general of the Netherlands in Singapore, dated May 31, 1882 and make its rejoinder in English-Chinese circles, which it was published in August 1882, with a pamphlet “The Deli Chinese Question”.

The Deli planters were able to demonstrate this with figures from the “protectorate” at Singapore and at Penang. In Singapore, 13,430 contracts had been signed, of which 2221 for Deli and 1470 for other Dutch possessions. And in Penang in the same year in 1881 contracts had been signed for Deli 5,267, for Serdang 662, for Langkat 1497.

Had the assistant protector there had trouble getting those 7,426 people to understand the terms? Weren’t the coolies led to the businesses by tandils, who had also contracted themselves? And why did many a coolie show a particular preference for a region, yes even for an enterprise, when they generally did not understand the conditions? However, the protector did not surrender.

Except for Hai Lok hong, very few Chinese left their country for Singapore or Penang to work outside the Straits or states under English protection. He also pointed to the repeated and vain efforts of the Deli planters to obtain direct emigration, vain efforts, not because the protectorate was opposed but because of Deli’s bad name, because of the abuses.

The Deli company had tried as early as 1873 to obtain coolies directly from China, to which, however, the Chinese Government objected. The chief clerk of the Deli-Mij had himself been to China and had already expressed the idea of a laukeh recruitment, that is, the mission of old-timers to China to return with free emigrants, who would then enter into a contract in Deli. When the Ocean opened a regular Deli-Singapore service in 1880, the Deli planters struck a deal for the transport from China with direct notes. That transport, however, had to go via Singapore, and while it was reasonable to think that the coolies with direct notes did not need the protector’s intervention, he had been involved in their contracts, even the slightest informality had proved sufficient to meet the coolies.

Other people are at Penang, according to the figures of the assistant protector. In 1879, 21,910 Chinese emigrants had arrived, 30,886 in 1880. In 1881 even 42,056. Of those 42,056, 8000 were for Sumatra, for the native states of Malacca 4000, for Siam 1500, for the British colonies, Rangoon and Calcutta 1500, stayed in the Straits 9000 and returning to China 7000.

No wonder if you only compare the conditions in the Straits with those of Sumatra. The sinkeh allied themselves in the Straits for 360 full days, which did not necessarily follow one another, and were paid a wage of $ 30-48 per year, of which $ 18-21 was deducted for passage through China and other expenses. The employer provided food, provided a kelamboo, a bamboo hat and some tools. We already got to know the Deli terms and conditions as much more advantageous. It was precisely in his defense to the allegation of opposition that the protector revealed himself, and if we consider the more unfavorable conditions on Malacca, we fully understand that there many Chinese and British entrepreneurs cheered at every official and non-official obstruction of emigration to Deli.

The Deli entrepreneurs pointed to the instructions and the official supervision under which the captains and lieutenants of the Chinese performed their ministry in the region and, as regards the lack of freedom of movement, the protector should make sure of it in Medan, Laboean, Bindjei, how much the coolies swarmed out on their two days off in the month. Not that alleged lack of freedom kept them in the country, but their own will. Their own statistics – there was not yet an official, because the registration of contracts was not yet fully arranged – showed that of the coolies, who were out of fault after one year and were free to leave, 80 to 90 percent stayed and again an agreement. Many remained in the country as vegetable growers, tailors, blacksmiths, toko keepers, sampan feeders.

In 1881, with letters of resignation, 1,648 coolies had left Deli, 233 Langkat, 224 Serdang, small figures compared to all the workers present, but large enough to dismiss the complaint about lack of freedom.

The businessmen who understood their importance were eager to see the coolies leave, wishing that they would bring their acquaintances elsewhere about Deli and return themselves. Had they not agreed in 1878 not to pay more commission to free coolies upon enlistment, and had they not limited the advance on re-engagement to $

The direct emigration to Deli came about in 1888, after five major tobacco companies, considering the situation untenable, had taken the initiative. The situation had become untenable due to the unreasonable increase in site costs. If the members of the Planters’ Association had agreed in 1885 to pay the same amount, 50 dollars (then equal to 125 guilders) for sinkeh, which the brokers and the protector thought was fair, they could not maintain that amount because there was not enough coolies were sent.

To be free to increase, a number of members withdrew from the association and in 1887 the association had to terminate the appointment for all members. Then the moment had come when the make-

Sinkehs are coolies who come to Deli for the first time. new students;

laukehs are those who were already employed there and are reconnecting.

A distinction was made between the coolies from different regions: Teo Tjoe and Hai Lok hong were more suitable for agriculture than Hakka. The amount of the site costs also varied according to the degree of suitability.

Pushing the cost up to $ 120 for Hai Lok hong and 75 for Hakka.

Now it became more tempting than ever for coolies to run out of Deli to the furnace trap or run away and stay in Deli and be recruited again, a deception instigated by agents and their accomplices.

In the past, the planters had foreseen against paying for the mataglaps of the Chinese officers. In 1888, the resident thought it better that the inspector at Laboean should supervise the resignation notes and contracts, and since the Government did not want to make any money available for this.

In 1889, it happened that at a company in Serdang, 63 coolies were hired on invalid discharge notes. Immediately, 38 were demanded by other companies and the Planters Committee issued a description of the other 25 to the members. It was clear that the enterprises would have been adequately assisted in the establishment of regulated, inexpensive immigration direct from regions with a decent farming population.

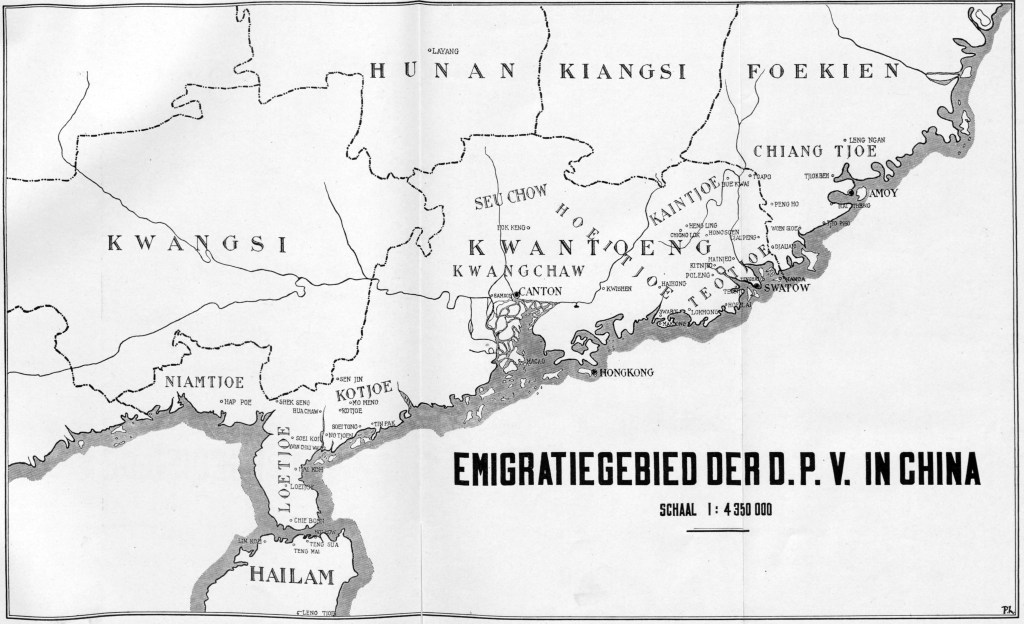

In 1886 an official for Chinese affairs had been commissioned by the Government to conduct ethnographic research in Foekien and Kwangtung. At the request of the planters, the mission was expanded with the promotion of regular emigration, for which the Deli, Deli- Batavia, Arendsburg, Amsterdam-Deli-Cie and the firm Naeher & Grob took the costs.

For two years, the Letter Resident -Planters Committee May 2, 1888: 240 attempts, two years of alternation between hope and disappointment, of continuous cooperation between the empowered official, two German trading houses at Amoy and Swatow, and German consulates to overcome the opposition of high Chinese officials who the emigration was generally ill-disposed.

In 1888 the steamship China first sailed up the Belawan River with 70 emigrants and that even then, expectations could not be high.

The five great bodies proposed on July 2, 1888, to the Planter Union for immigration to make a common institution, the expenses being divided in proportion to the picols of tobacco obtained. The association decided on this and set up an “Immigrant Bureau”. over which the Planters Committee would exercise general supervision. Thus, after many woes, the institution was born, which has been of the greatest use to the settlement in Deli ever since.

The task of the office became the management and promotion of direct emigration, counteracting the influence of the coolie brokers, and replenishing the current shortage of coolies by recruiting in the Straits.

The compensation to the Immigrant Bureau was set at $ 60 per coolie, covering all costs of recruiting and crossing. The German firm at Swatow became the agent of the Bureau for the Affairs in the ports of southern China, namely Amoy, Swatow, Hoihow, Pakhoi and Hong Kong.

With the establishment of the Immigrant Bureau, the Planters’ Association had to remain vigilant against all kinds of danger, sometimes from the sticking brokers and defamatory Chinese papers, sometimes from those of the Chinese government officials.

In 1889 a government official for Chinese affairs, in whom the Chinese rulers saw a kind of protector, could go to China as a representative of the Planters Committee. The following year, efforts in the Dutch East Indies and the Netherlands to improve the consular representation of the Netherlands were crowned with the appointment of a salaried consul general for southern China.

The association had first chartered boats, in 1890, it decided to provide a fixed line between the Chinese ports and Deli. Unfortunately, they could not yet be ships under the Dutch flag, for the emigrant ships needed much support from the consuls in Chinese ports. A sharp attack on the young institution formed a regulation on the emigration to Deli, which the Chinese Government had already threatened twice and which they now suddenly introduced in 1891. Immediately in its first article, it recommended the appointment of Chinese consuls in Deli and further demanded higher payments for the coolies, a ban on opium.

The effect of those regulations would have been the death of emigration because it also required that the coolies would get their hands on $ 5 and the rest would be sent to the family in China. One can only understand this stranger’s claim if one keeps in mind that the emigration in Foekiën and Kwantung was a matter for the large family groups.

Related families were “klans”; and the client boards authorized emigration, cared for women and children who were left behind. That is a state interest which the regulations of the Chinese Government would promote. But the interest of the state, thus served, was not in keeping with the intention of the coolie, who, after all, wanted to receive the wages for his labor in his own hands. His daily existence abroad would lose all appeal to him if he could not get beyond the merit of a living.

Fortunately, the regulations did not work. The planters also encountered setbacks in the work of immigration outside the government officials: it was the mutual feuds of the tribes and the epidemics that hindered them. The rice harvest in Foekiën or Kwantoeng was great; even then, there was little desire to leave their own region. Large inquiries for Perak, Borneo, and Siak and the opposition of the brokers kept the figure of the immigrants still quite low in 1888. The beheading of a broker in Swatow, who worked for Deli, caused panic among the coolies. Nevertheless, progress was made in direct landings, and Deli was no longer in China as it used to be for a section of the Straits, thanks to the regular monthly steam sailing between Deli and Chinese ports; thanks also to the credit balances of the coolies.

Planters and the Government in Deli did take measures against the transmission of the disease, but in 1899 the Government thought of a temporary ban on immigration from Swatow, where the plague reigned again. The Planters Association immediately set up a quarantine station on the island of Berhala, which was transferred to the Government in the following year. It never had to serve the plague, but it did serve cholera in 1902. Later the quarantine was transferred to Belawan.

Even before the end of the nineteenth century, the Planters Association could regard direct immigration as fairly assured. The figures for the years 1888-1902 are as follows: 1152, 5176, 6666, 5351, 2160, 5152, 5607, 8163, 6661, 4435, 5105, 7561, 6922, 5556, 7181. The figure for 1892 was low (2160 ) due to low demand related to the crisis; that of 1897 was printed because there was a lot of fighting in Hoelai and Haihong.

In 1890 the Straits number was still over two thousand, in 1899, it had fallen to 331, in 1902 to 3. In the years mentioned, Swatow was the main place of departure, Amoy and Hong Kong gave nothing after 1890, Pakhoe in 1891 virtually nothing more, Hoihow after 1896 nothing more. The ununited enterprises continued to acquire workers from the Straits and also employed coolies who, after contract labor elsewhere, had become free men and had not yet returned to their country. Significant were the amounts paid by the Immigrant Office. In 1902 there were 133 tobacco companies, 75 of which were affiliated with the Deli-Planters Association.

Chinese coolies in Deli transferred to China: in 1888 it was $ 40,100, in 1891 as early as $ 78,778, in 1895 it was 201649, the highest year in the series is 1899 with 260124; in 1902, it was 177370 again; for each year the savings figure attests to the ample income which the tobacco cultivation of Deli was able to provide to the Chinese immigrant. And that was allowed, where the Chinese were considered indispensable for the care of fields and crops.

The laukeh recruitment recommended by Cremer in 1876 was not abandoned after the intervention of the Immigrants Bureau. The Office had from now on recruited, through the mediation of the German firm, as an agent at Swatow, which agency arranged the passage of those who came to present themselves as expatriates for Deli. In addition, the companies continued to send veterans, laukeh’s, to publicize Deli in the Swatow hinterland and other oat towns, as well as to return with acquaintances or relatives who also obtained passage through the agency.

The Immigrants Bureau received reports from its agency and received the laukeh’s company, taking into account the arrival of the laukeh friends in the distribution of the number of immigrants ordered by the Bureau for all enterprises. If one company had asked fifty of them from the Bureau, and if the laukeh recruitment had made ten, he got 40 from the Bureau.

The laukeh with his savings and the dispatches in checks of savings by the Immigrant Bureau for payment by the agency to the entitled families were Deli’s best recommendation in the emigrant regions of the Celestial Empire.

In 1890, 873 coolies returned directly to China, taking with them $ 102,586 of saved money in the form of non-endorsable bills of exchange; in 1892, 1,127 went back to China with $ 80,000; in 1896, 1,729 on their return trip to China took checks from the Immigrant Bureau for $ 202354 and the Bureau sent $ 3,499 in bills. Ample of income, if it is true, that those sums included sums which some head tusks transferred to the shops, coolie hotels, in China, to facilitate the arrival of new emigrants.

The laukeh recruitment of companies themselves involved a danger that was seen but also faced. When the laukeh went to his village and won some healthy acquaintances, farmers, for his venture in Deli, his mission was successful, and the cost of premiums was not in vain. But when the enterprise had given the laukeh ample funds, he could make it easier for himself: he did not go inland but went at Swatow to the shops, the quarters of candidate coolies, which the agency gave to the Immigrant Bureau would send, or he would go to Chinese coolie recruiters and take his people from there against intent. The Planters’ Association could take more or less effective precautions against such practices, but there was an even greater danger.

The companies sent with letters of recommendation, Chinese brokers, grocers, that is, people who were not laukehs, to China to recruit and to return as leader or commander of sinkehs. Such leaders, keh-thaus, traveling several times between China and Deli, could acquire a taste and a certain knack for it, and make their recruitment a profession of their own. These people would gradually be able to take over the entire recruitment outside the Immigrant Bureau and at higher prices, and the once-so-cursed Singapore and Penang brokerage would come to Swatow with all its evil.

For quite soon, the laukeh recruitment and the use of keh-thau had the lion’s share in the immigration of Deli, utterly outstripping the recruitment of the Immigrant Office and its agency, so that the Office became more of an institution for transport, the reception of the coolies and the associated management.

In 1903 the leader of the Immigrant Bureau could write: As to the further disregard of the regulations, the recruitment of coolies from the interior is indeed one of the exceptions; the percentage brought in by actual laukehs of the enterprise is small and limited to a few enterprises, and so the keh-thau-laukeh has become an inescapable fact.

Is the great advantage that immigration is producing now, that the sinkehs are arriving in great numbers, and, though not to a sufficient degree, a great deal of the need is satisfied that the content of the coolies. Slthough the experiences there will be different, may generally be called favorable, are all these signs of a solid prosperous situation or is it of a previous nature, which will later show that one was on the wrong track and the results have only been obtained with calling for help from the wrong means?

According to the report of the first labor inspector, in 1902, the members of the Planters Association employed over 37,000 Chinese, nearly 15,000 Javanese, 6,000 Javanese women, and 5,000 other Easterners.

In China the contract with the Asiatische Küstenfahrt Gesellschaft, agents of the firm of Meyer Co., extended until March 1901 and that with the firm Lauts Haesloop, which ended December 13, 1899, to December 31, 1903.

In 1923 seemed to yield poor results for China’s emigration, the Secretary of Association madean investigation into China. It turned out that, in addition to the obstacles caused by the riots and turbulent movements in the South, also the relationship of the shop with China Emigration.

Several measures were taken subsequently taken in order to promote emigration again. Tek Piak laokehs was asked to expand the emigration area, Loetjoes.

As early as June, some improvement in the process of emigration was observed, the great supply was not to take place until September. An unfavorable paddy harvest.

As a result, in September and then in October and November, 1390 and 1276 new ones emigrated to Deli. “Tek Piak” laokehs alone produced no less than 1500 sinkehs in a short time.

In the long run, however, the recruitment of Tek Piak laokehs did not give any satisfaction, especially where this institute could give rise to messes. It had turned out that their emergence greatly diminished the sense of responsibility of the main tandils for emigration and the

enterprise in that way did not always get the people it wanted.

For these reasons, the emigration of Tek Piak laokehs off. The same year it was through

Planters Committee The main association, founded in 1920, was disbanded.

Leave a comment