The actual planting and tilling of the soil is done by Chinese coolies, who are imported in great numbers directly from China and who have a permanent contract with the entrepreneurs, who are obliged to provide housing and partial nursing in addition to their wages. For their use, large, airy houses, so-called kongsis, are being built on the various plantations, where they find a good residence. In the small shops, which immediately settle around and near the kongsis, they can buy their daily necessities.

A tobacco company has seen from a bird’s-eye view, something of a small village, through the numerous dwellings of supervisors and officials, the great fermentation barns, drying sheds, stables and shacks.

The tobacco fields lie fallow alternately for seven to eight years. After a harvest there always follows such an era of rest, in which the soil is only planted with rice by the population for one year and is left to themselves.

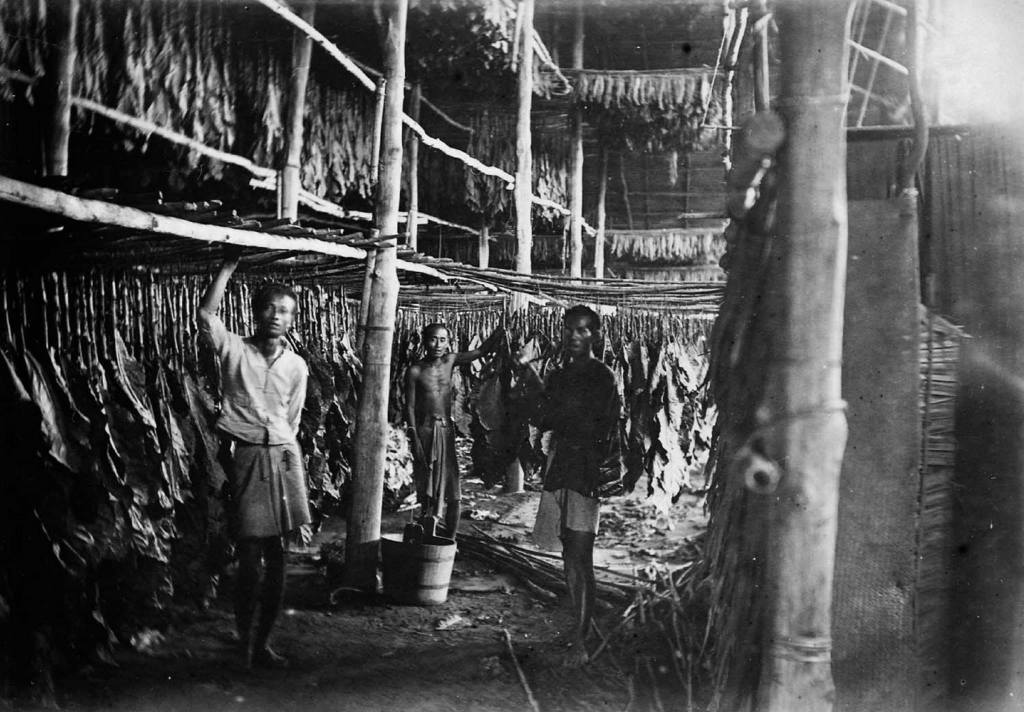

In the months of January, February and March, the fields are prepared for the reception of the young tobacco plants. Sown in nursery beds, the tobacco seed soon emerges and develops into a small, delicate plant called “the bibit”, which is treated with the utmost care and then transplanted into the digged and burnt-down soils of the woods. At the end of June or July, the tobacco trees are fully grown, are cut and placed in the drying sheds. There the green leaves dry until they take on a brown-yellow color and are suitable for undergoing a long heating process in the fermentation shed, which must serve to give the required color, flexibility and elasticity to the tobacco. Fermentation takes place by placing the tobacco on high piles, each of which is turned and turned over with great care, so that the heat caused by scalding does not become too great and therefore harmful to the plant. Then it is sorted into different colors, lengths and qualities; an operation that requires great patience, skill and practice. After sorting comes bundling and packaging, then shipping and finally selling – ‘le fin mot de l’histoire!’ The planters will, especially in the last few years, over the latter satisfied, because since the Americans chose our Sumatra tobaccos to their own crops, the Delian gold mines have become almost diamond fields!

However, that all these different processes require constant supervision, an exerted activity, will surprise no one, and anyone who is well aware of Oud-Holland would like to grant the planters their success, for tobacco is nowadays the main article, that strange traders to our markets in Holland, which makes money from hundreds who remain quietly in Patria, also enjoying the efforts of the Delian planters!

I was in conversation with one of the chiefs in the large, spacious shop of Messrs Katz & Co., in Medan, when a neatly tidy sedan, drawn by two fiery Batak horses, drove up. The looper, we would say here, the palfrenier, jumped behind the carriage, humbly opened the door, and the just passing Malays crouched down, making “sembah,” while a few Europeans greeted politely.

– The Sultan of Deli! the chief said softly to whom I spoke. – Excuse me? He went to meet him.

A man of medium size, slim and well-built, in very well-groomed European dress, got out.

He wore a gray fancy morning coat of thin fabric, a white piqué vest, neat linen collar, cuffs and shirt, and a slip-tie sparkling with a diamond pin. His light trousers fell immaculately over fine lacquered shoes, and I noticed that instead of an ordinary round or helmet hat he wore a cap of dark cloth, with a red ball and with narrow gold piping, which, by its peculiar shape, was attached to a crown made you think. He looked very good on the black hair, already turning gray here and there on the temples. His face dark in color, but whiter than that of a Sumatran, had more of an Oriental than a Malay type and was regular in shape. Small, lively eyes and a kind mouth gave it a pleasant expression, which, when it spoke, became still more pleasant. A thin black gag hung over his lips, which opened with a pleasant smile, revealing his enviably white teeth when he spoke. A few marks on the cheeks, nose and chin indicated that he had endured childhood illness.

He walked with slow, small steps through the toko, looked at a few things, always chatting with the chief, who seemed to be very personal with him and from whom he repeatedly inquired.

– Would you like to be introduced to the Sultan? asked one of the gentlemen who were busy in the toko.

– Love!

Then come along, and as we approached, he said: Now you can give yourself a little Malay, for the Sultan does not speak a word of Dutch.

I was introduced as ‘Mr van Maurik, a gentleman who writes books and newspapers.’

The Sultan looked at me for a moment with his small, keen eyes, inquiringly at me, asked the chief something that I did not understand, looked at me – I must admit; that he was doing it very modestly – well again, then took a step towards me and reached out to me. “What a small hand, I thought, and involuntarily I looked at his feet – and what a neat little feet, they look like lady’s feet!”

– The gentleman is coming to visit Medan for his trade relations and to gather material for a book that he will write about India, the chief said in Malay – I understood it well enough – but when the Sultan approached me and asked :

– How do you find Sumatra, how do you like it here? I was pretty much tongue-tied, my knowledge of Malay was still in her birth, I noticed that all too clearly at the time. But I had to say something too, and … I said something, but when I did it as good and bad as I could, the chief’s face fell and he said hastily: silent, because you are sinning horribly against the label. You can say to the Sultan.

– Now! isn’t that polite enough?

– Really not, you had to say Tuvanku – that is, “My commander.”

– But it’s my commander, isn’t it!

– It doesn’t matter, it’s his title. And now my blunder again to make amends, he said: – Tuwankoe! Mr. van Maurik has not addressed you as it should be, but he is strange here and so ….

– Oh, tida apa! (That is nothing) the Sultan replied very courteously – for, he added in Malay: “Sir doesn’t know any better!” and very politely he reached out to me again to prove that he was not angry about it.

The Tuvanku inquired – the chief acting as interpreter – how my journey had been, whether I would be in Medan for a long time, thought to stay and so on and finally asked if I thought to write about Medan in that book too.

– Sure! Toewankoe!

– About me too?

– Of course!

I saw a gleam in his small vivid eyes and an almost imperceptible smile around his mouth, indicating a pleasant quick thought. He straightened up a little more and asked with a small tone of self-satisfaction in his voice:

– Would you like to see my palace too? I am going home tightly and will be happy to receive you. – You can see that we also have beautiful buildings here in Medan, I will give you a photography of them.

– Please! It will be a great honor to me.

– You seem to like him quite a bit, said my friendly interpreter and if you want I will ask the Sultan for his portrait for you too, you can print it right away in your book – then you will certainly have something in it that no other can have, because the Tuvankoe is usually not generous with his portraits, but he looks at you rather graciously. Yes! gentlemen authors always have an advantage; You understand, newspapers and books are important things in the eyes of the Sultan and he sees the people who make or write them with different eyes than us traders, which is why I did not introduce you in your quality as a cigar manufacturer!

– Understood!

The Sultan looked at me, while the chief asked him for his portrait on my behalf, inquiringly at me, lit a cigarette from a neatly chiselled silver case – offered me one too, and asked: “Would sir like it?”

– Very gladly! Please!

– And will you print it in your book?

– Doubtless!

Again I saw an almost imperceptible glimpse of childlike satisfaction when he said:

– Then I’ll send it to you with my signature on it. This afternoon you can come and see my palace.

Signature of the Sultan of Deli

– I am most grateful to you in advance, Toewankoe!

The Sultan gave me a friendly nod, as if to say, The audience is over, and, after making some more purchases, got back into his carriage.

Some time later he sent me his portrait, which I print here as well as his signature.

That signature means: MaÄmoen Alrassid Perkasa Alam Shah , which being translated means: The faithful (maämun), the just (alrassid) , the beautiful, (perkasa) – perhaps the same root can be found in this word as in the old German Perchta – New High German: Bertha (the beautiful) – Lord of the world (alam shah) . Shah = Lord, is still the title of the rulers of Persia.

All these designations are certainly sufficient indications of the great excellence and highness of the wearer. Incidentally, almost all princes in the Sumatran countries call themselves Lord of the world , something which does not give a too favorable impression of their modesty and geographic knowledge.

The official title with which the Sultan is addressed is Serial-paduka, Tanku Soelthan , literally translated Seri = exalted – showing the same root as the English Sir – the Latin Caesar and the German Kaiser , perhaps also the Russian Tsar. Padoeka (sanskrit) = shoes – probably having the same root as ‘t Spaansche Zapato (shoe) and’ t Fransche ‘patte.’

Tuan ku , descending from the same root as the Malay tua = old or dewa = spirit, god and cow or aku = I = ego (Latin).

Thus together signifying my lord.

This entire title, Serie padoeka wankoe Soelthan, is common in official documents, even when Europeans write to the Sultan. A native, on the other hand, would not even dare to turn to the lofty shoes of his prince, but addresses his letters: Kabawah aimi kaoets = “on the dust under my lord’s shoes.”

Surely more reverence and submission is inconceivable – one could almost argue that it is all too reverent.

In general the labeling in Malay courts, although little known, is much stricter and more complex than in any European court.

Not only is the title and allocation for each monarch determined with the utmost precision, but also the posture, even the gestures and the facial expression are carefully prescribed.

Never will a Malay even a Tengkoe – a prince more or less entrusted to the Sultan or a Datu, a former independent prince, now obliged to borrow – dare to address his commander without squatting and bringing his flat hands together before his forehead. and make sembah. That is why the Natives call every address of the Sultan ‘sembah’.

The Sultan himself only orders: ‘titah’ or ‘sabdah’. On the other hand, in a conversation of long duration or in the presence of Europeans or at gala occasions which make a continuous sembah impossible, the label demands that the person who speaks with the Sultan leans against or clings to something, and if not that either. it is feasible to keep standing with your back bent as much as possible, constantly looking at the Sultan.

The adat (label) means that the Sultan himself never looks at the person speaking to him, but looks over him or next to him, as it were.

Also very peculiar at court is the use of the pronoun, I Akoe in Malay. In ordinary life it may not be used at all, it is only permitted to the Sultan, and to officers to their subordinates, to the superiors to their inferiors. The use of ‘akoe’ always expresses command, wrath, contempt or a strong sense of self-worth towards the person addressed.

In addition, “akoo” or “cow” is used in conjunction with other words like Tuwang cow, my commander, or Tengkoe (prince), Handai cow (my friend), when a confidential note is struck. Also in amorous language like: buwah hâtikoe (fruit of my heart) – we would simply say: my heart beat – also in Bidji mata-cow (core of my eye, apple of my eye).

The Malay uses in common slang for. I if higher to inferior speak ‘kita’ or ‘kami’ = we. In the past this was common in the European courts, in a few small German courts this ‘wir’ is still common, while it is still generally used in official government documents. Princes, nobles, and natives, when speaking among themselves for me, use the word saya , which actually means “servant,” thus always speaking courteously your servant wants or does or desires this or that.

The courtesy of the Malay greats among themselves is oppressive and troublesome – but the courtesy of the common Malay really does not hinder the European, for the Sumatrans are rather brutal and curt than polite or submissive, quite different from the Javanese, who are softer. of nature and more humble in nature, to respect the European much more.

The Sultan of Deli, however, can be set as an example to his subjects, for he is a man in all respects kind, courteous and benevolent, who, even by European standards, is a very likeable personality.

He strives with great tact to avoid anything that in the eyes of Europeans could detract from his prestige in the least or the slightest – but towards his subjects and Datoes or Tengkoes he is the all-powerful, untouchable commander, the absolute prince. whose utterances always with a most reverent sembah and a monotonous “Tuwanku!” of which, curiously enough, usually only the last syllable ‘cow’ is audible, are answered.

In his views, opinions and customs he is a real ‘Orang Islam’, a Mahomedan, who has all the advantages that faith, enjoy and appreciate. He lives in his palace, that is, in a small section of it, preferably very simple, but good, entirely according to the customs and customs of Islam, but he has nevertheless managed to give himself a European tint, which certainly does not displease him. and makes it attractive to the eyes of Europeans.

When one sees him riding in his neat and tidy equipage – the Sultan loves fine carriages and horses – one would, if one did not pay attention to the strange headdress of the coachmen, who, as elsewhere on their headscarves, wear a livery hat with band and cockade, think he was a great European. Everything looks fine and chic, not too colorful or too colorful, but really neat, gentlemanlike; the harnesses of the horses are neat, of first quality, and the carriages compare favorably with those of others. I have often seen private carriages of distinguished Chinese, which did not look any better than ordinary “rental stuff” from a Dutch stable owner.

The Sultan usually dresses with great care, but simply, in fancy suits of good cut – on festive occasions in a black skirt and white tie – only at large gala receptions or official parties in a beautiful uniform with an embroidered collar, gold shoulder straps and Brandenbourgs .

He is a great cycling enthusiast and has even donated a well-appointed cycling track to Deli’s residents.

Without a doubt, the Tuvanku is a man who will do everything he can to make himself loved. He is an excellent, generous host, who repeatedly gives very pleasant and beautiful dance parties in his beautiful palace, in Eastern style, built by a Dutch architect.

These balls, given in the rich, spacious, extraordinarily elegant reception room, are among the most sought after festivities, and those who have the honor of being invited to do so will spend some hours full of variety, pleasure and opulence. ‘Something for everyone’ is the Sultan’s slogan, because he ensures that everyone can enjoy themselves entertain, the ioner with dancing, the elderly with card games or music.

In those beautiful halls, brilliant with light, regally furnished by the well-known Hague firm Mutters (the furniture, etc., of the reception room only cost sixty thousand guilders), the elite of the Medans ladies and gentlemen moves with the authorities, and Full of princely generosity, the Sultan still pays homage to the real Eastern custom at such feasts to give his guests beautiful gifts as tanda-mata (souvenirs) before they go home. I saw, among other things, beautiful gold-embroidered silk sarongs and slippers, which the Toewankoe gave to ladies, beautiful walking sticks with artfully carved ivory buttons, which he had honored to gentlemen visitors.

In his salons, in his palace, he is the commander, the ‘Alam Shah’ – but in politics they would not dare to give him that title. He is an independent Sultan – but the Dutch government always speaks a paternal word when he has to make a decision that is too important for him to take alone.

When one sees the Sultan in his neat, elegant equipage driving through Medan and notices the honors which the population does not owe him, one is inclined to think – be it in the innermost part of his heart: that is once more a prince to be envied – he has all the pleasures of his office, and he does not even share the burden with others. Such a paternal government is not so bad after all!

But on earth – Heaven certainly wants it so – there may be no unmixed pleasure, no pure happiness, and therefore a Sultan is usually blessed with a great number of relatives, ‘sudaras’, who, as if this speaks for itself, draw from the Sultan’s dish. take a fork, and sometimes do not spare themselves from attacking the fattest snacks. If the commander is not too kind-hearted and at hand enough to tap those greedy relatives on his fingers in time, then his dish will remain well-filled and tasty.

some commander at last became the slave of his friends and stomachs, and finally found that, where going off and not getting enough, an empty dish is the end.

The Sultan of Deli need not fear such a thing, for he is by Allah’s blessing a very wealthy prince and his resources are many. The Datus of Hampéran-Perak, of Soengal, of Kampong Bahru, and of Senembah, as well as the Tengkoe of Pertjut (a member of the ruling family) are obliged to loan him and must give him half of their annual income.

And when it is now considered that almost all of the soil of Deli belongs to the aforementioned princes, it can be reckoned on his fingers that the Sultan of Deli will not soon become ill.

He has an open eye and ear to European civilization, and is not at all conservative, and therefore readily adopts Western customs and habits as far as his faith permits. He is delightful and likes to buy the latest gadgets – why shouldn’t he – after all, he can say with Jesus Sirach: ‘ Whoever has money and lacks something, saves for others and friends will revell with his goodness ‘ .

A court like his is not without significance for the many toko’s in Medan, for the repeated festivities bring with them important orders themselves, and certainly traders and private individuals will wish the hospitable, development and civilization-seeking Sultan of Deli a long and happy reign. .

Indrukken van een ‘Tòtòk'(1897)–Justus van Maurik. Indische typen en schetsen

https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/maur005indr01_01/maur005indr01_01_0020.php

Leave a comment