EMIGRANTS AND OTHER STORIES BY M. H. SZÉKELY-LULOFS

“A Seng !!”… “Toewan”…

Somewhere, way back from the farthest outbuildings of the assistant’s house, the long-drawn-out reverberation sounded. A minute later, panting and with his bathtub only half on, A Seng ran into the front veranda, then stood waiting and catching his breath in front of Tuan Pieter Klaassen. A lock of his stiff black hair had fallen between his lopsided Chinese eyes, and somehow behind the rigid seriousness of his yellow face, there was a never-fading smile. That smile gave A Seng’s face a faint hue of audacity, though his devoutly clasped fingers and questioningly hunched shoulders denied all appearance of impudence.

The two men looked at each other in silence for a second. That meant, A Seng knew that ladies guests were to be expected. If Pieter Klaassen did not say: “Beer!” or Pait! but when A Seng continued to stare in somber silence, ladies’ guests arrived. A Seng knew his tuan through and through. He knew the smallest traits of Pieter Klaassen’s character with oriental delicacy of psychology. And for tuan, ladies visit was quite a chore. That was not surprising when you consider that there is a lot of fun in the whole house

Two plates, one knife and fork, one spoon, one glass and one teacup. Pieter Klaassen only drank coffee from that teacup. Finally, Pieter Klaassen said: “We are having visitors, A Seng”, “Ladies, tuan?” … A Seng really did not have to ask that question at all. He also only did her out of oriental courtesy, so as not to betray that he had already seen through Pieter Klaassen’s difficulties.

“Ladies too, A Seng. Two! And two tansl And they keep eating here!”

“Good!” said A Seng. Because in addition to being a good psychologist, A Seng was also an almost criminal fatalist. The good God would help, was A Seng’s motto. Because, isn’t it – thought A Seng – what else would you have a good God. Pieter Klaassen’s face for “If you put it together properly, you get ten guilders.”

A Seng was delighted. The smile emerged from its hidden depth and slid wide and grinning past A Seng’s mouth. The sacred image of the dice mat loomed in front of his glittering slit eyes.

Then Pieter Klaassen said: “Beer!” And A Seng ran to retrieve a bottle from the ice chest. With that, all the clouds had been wiped from the sky and life went back to normal.

This afternoon A Seng was gone. No one could tell where he was. And because Pieter Klaassen was not at home either, but was walking around in the blazing tobacco fields between the green growing tobacco plants and the diligently curved yellow coolie bodies, the assistant’s house lay deserted all afternoon and deserted in the shrill, stinging sunlight, in the scorching heat that trembled over the barren, thirsty land.

But an hour before the guests arrived, A Seng appeared at the very farthest end of the long, endless long, straight plant road, meandering slightly on his overloaded bicycle, sweating and rickety. Pieter Klaassen did not ask how he had packed his bicycle so full. That was A Seng’s business!

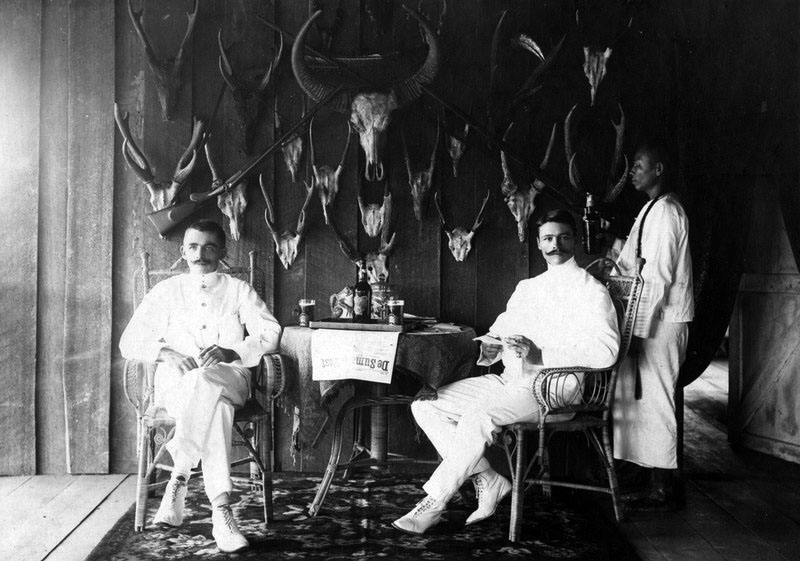

Still a bit worried and uncertain, Pietër Klaassen was waiting for his guests. He had shaved his rusty beard stubble and put on a freshly starched, creaky stiff white suit, but all that did not alter the fact that he had placed his fate in A Seng’s hands. If A Seng deserted him, made a mistake, then he was hopelessly embarrassed. He was a ‘bachelor’ and ‘bachelors’ were usually forgiven a few things… but there were ‘neat bachelors’ and ‘less neat bachelors’ and Pieter Klaassen was without a doubt one of the last. Because he drank coffee from a teacup and he drank beer instead of tea and gin instead of port or vermouth. He was in debt and a housekeeper. And another housekeeper, who made room for another every month, for none of them tolerated the domination of A Seng.

Those housekeepers looked alike like two drops of water. They were all about the same age, they all wore golden English pounds like pins on their baths, they all wore the same clattering velvet slippers embroidered with gold thread, and they all had the same screaming voice, which was flattering or screeching in exactly the same way. could be anger. They only had another name. Sometimes it was wrong to see Klaassen, because it was confusing to remember twelve female names in a year.

Pieter Klaassen usually did not know exactly why the 2nd left. They had a fight with A Seng or A Seng’s wife or A Seng had a fight with her. And that was the most common. Not that it hurt Pieter Klaassen… oh no, A Seng always made sure that there was a new one in the place of the one who, on the contrary, drove deeply offended and wronged out of the yard in her little sado.

But all these stories were not Pieter Klaassen’s only sin. He didn’t write home often enough either, for he said there was nothing to write about the plant road. And he did not read a newspaper either, because he thought that if you could only plant tobacco well, then you had ‘nothing to buy’ with the world. And not only that Pieter Klaassen never went to church because there was no church within fifty kilometers, but he also had drunk gin once the minister from the city had made his tour and Pieter Klaassen had come to visit.

It was for all these things that the ladies, as they very occasionally came to visit Pieter Klaassen in his ramshackle house on the ramshackle plant road, in the middle of the lalang and the weeds, without the usual yer tendering for bachelors, without the usual his lonely existence, ruthlessly peeping about what defects could be found in this household.

And the two men knew that, and that is why there was always that painful, tragic second of silence between them when a ladies visit had been announced. Until A Seng spoke, the redeeming word had promised that everything would be in order. Pieter Klaassen, in turn, promised the traditional tenner and A Seng, with a radiant face, ran to the ice chest to dig up the usual bottle of beer under the glittering white bars of ice.

And although A Seng had always faithfully kept his word, Pieter always waited with a little uncertainty for the course of events. But it was always not too bad! … The ladies tripped in cheerfully and gracefully. The husbands grumbled a cheerful greeting. And Pieter Klaassen pretended that there was no mistake in the air and that every evening he held receptions for dozens of critical, scrutinizing ladies who suspected with insulted self-esteem that A Seng valued her in the same way as the housekeepers. Yes, I forgot to tell you. Actually, because of this suspicion, Pieter Klaassen’s biggest sin was that he did not want to fire A Seng, but kept his hand above his head in all storms. And actually, that’s why that the ladies smiled so vigorously whether the lemonade was cold enough and, to her inner regret, found that the knives were always in the right place next to the plate and the table was even set with flowers. They saw that the tablecloth was not a real tablecloth, but an ordinary cotton cloth. But that cloth was neatly ironed, and you couldn’t blame even the worst bachelor for not seeing the difference between cotton and damask. Naturally, the ladies did not know that the table cloth was not a cotton cloth, but Pieter Klaassen’s bedsheet, which was quickly ironed on for this occasion. That was a tender and sparingly kept secret between Pieter Klaassen and A Seng.

On this evening, the ice-cold beer and the well-cooled lemonade appeared in neat glasses with a sharpened rim.

“Cheers,” said Pieter. “Cheers!” said the guests, let the lavender moisture slide through their thirsty throats and the men secretly wondered why the ice at their home was always less cold than at Pieter Klaassen, and in silence, an appreciative glance passed from their eyes over the smooth, yellow face of A Seng, where there was that smile, which seemed an impudence and which was neither a smile nor an impudence.

One of the ladies, however, held her glass up to the light and said: “You already have your glassware from Hoying, I see, Mr Klaassen. And exactly the same pattern as us … That is just a coincidence at the same company … But we have had that before, haven’t we, Annannie? … “Then she drank and said:” That is an objection of Hoying … “And it sounded as if she meant: “That’s a nuisance to have to encapsulate yourself like that …” Then Pieter Klaassen shifted a bit in his chair. Smiled. “Yes…. hm…. That does happen…. at Hoying…” In the meantime he peeked at A Seng, who served diligently and looked crisp and clear. But A Seng’s face was a smooth mask of contentment. The good God did not abandon him and what did he know about the existence of Hoying? … He only knew that married tuan have glasses and unmarried not. And that, when the married people come to visit the unmarried couples, you will borrow those natural glasses. The wife of that tuan need not notice any of this. By the way, he still sleeps in the afternoon. You ensure good understanding to be a thing with the babu of madam … and the matter is okay … is doubly okay, because in the short term you can just have an amour with babu.

Such evenings always lift smoothly and cheerfully and in harmony. After all, no one could have imagined that this degenerate Klaassen could have such a refined and civilized taste in his household affairs! For it turned out that he had not only exactly such glasses as the one family, but also exactly such finger cups and exactly such fruit knives. And spoons and forks like the other family. And even just such glass cloths with a red border, of which A Seng wore one lightly over his shoulder when he presented the duck disguised as hare pepper. The fact that the tablecloth and napkins were not exactly the same was only the result of the fact that white ladies’ linen cupboards are locked and the key, when those ladies are sleeping, is under her pillow. So that here then even the weakest flesh and the most willing spirit were of no avail. But that glass cloth could always be obtained and it always turned out to be the peace pipe, which is, of course, an unacceptable comparison, but it was so.

That glass cloth wiped out all blood feuds. Whitewashed all the sins of the landlord: the teacup, which was not used for tea, but for coffee, the beer and gin, the twelve housekeepers a year, the insult inflicted on the clergyman …

An hour after the guests had left, in the in the middle of the night, A Seng paddled sweating and panting along the edges of the forest, over winding and dull roads with his fully loaded bicycle to faithfully and honestly deliver all the borrowed bulls to the various babus. While in the meantime, Pieter Klaassen fell asleep with a relieved heart on the table that A Seng had quickly tucked over the mattress for him …

The second day of such a visit was always a sad day in the Pieter Klaassen house. Then A Seng would have had his ten. Then he would have indulged in the dice with all his passion. Then he would not only have lost the ten guilders but also what remained of his monthly wages and his wife’s clothes. And also the ten guilders advance which he received during this day from Pieter Klaassen, and which in turn borrowed it from his Chinese grocer by coupon. That then meant that Pieter Klaassen in this sinful world again had twenty guilders more in debt, because he had also obtained the ten guilders as a reward in this way. But Pieter Klaassen was not sad about that. He was gloomy and tired of life because, on this day, A Seng neglected all his duties. A Seng sat in front of his room and smoked and listened in silence to the allegations of his wife, who had more than necessary suspicions about the babu affairs. A Seng forgot to let go of the chickens so that they made a hell of a spectacle in the loft and robbed Pieter of his afternoon nap. He forgot to give the monkey a drink, which jumped on his chain around his pole, screaming. He forgot, and that was the worst, he forgot to put the beer on ice and he also forgot to get gin. And so Pieter Klaassen remained sober all day long. And this day he wrote home because he had nothing else to do. The lack of the jeneverkraik brought him a restless dissatisfaction. And when he wrote, he was copying, of course the loneliness and the monotonous work. He wrote that there was usually nothing to write because this life was an eternally empty, monotonous, and mind-numbing life.

He felt this was becoming more disastrous. On other days he didn’t think about all these things. Only on this day. When the letter was finished, Pieter Klaassen looked around in his gloomy, sparsely lofted house for further activities. He tried to smoke. But now that he was so sober, he saw all the unpleasantness of his house. He saw the gloomy dark-oiled walls, where tjitjaks gobble up mosquitoes. He saw the beams and the battens that supported the roof. He saw that instead of a ceiling, there was a black gaping dark hole, a dark-deep abyss, which, strangely enough, hung above his head and from which all kinds of eerie dark shadows and ghosts were sliding down on him. The same kind of shadows and shadows that creep about in his garden between the lalang and the weeds, and he heard a thousand strangers, disturbing sounds rushed from the edge of the forest to his house. And he heard in those oppressive noises the oppressive silence that crept around him, her long black clasping hands reaching out to his throat and to his heart so that he could barely breathe.

He thought about what his life had actually become. Slovene and toil in a land that was not his own. Oak day from the beginning. Oak day, which was exactly the same as the previous one. Only that they had a different name. But what cared you what that name was? … Did it make a difference whether a day was called Monday or Saturday? … Did it make a difference whether a housekeeper was called Minah or Sarinah? … Did it make a difference whether you lived on plant road no. or at plant road no. seven? … Did not grow the same lalang and the same weeds everywhere? … Weren’t the same houses everywhere with their dark, oiled walls and the dark hole above your head? .. And the same shadows and shadows were not crawling everywhere, ready to blow your throat and your heart at the first opportunity to pinch shut? …

Pieter Klaassen was homesick this evening. He thought of the rain in the Rotterdam harbors. On Wednesday afternoon’s barrel organ. On his father’s stinking pipe. By his mother’s black, run-off shoes. He thought of the girl from the liquorice and candy shop on the corner. And then he realized that from now on, he would start a new life. That when I wouldn’t drink anymore. And would have no more housekeepers. That he would fire Seng, because that robber actually stole him more than brutally. He thought he would pay his debts and be frugal from now on. And with that, he had found his occupation. He sat down at the writing table again and dug up piles of envelopes from the drawers. Some torn open, most still closed. Envelopes from months ago .. Accounts… He sorted them. He took a large blank paper and wrote long series of numbers on it. And he added those series of numbers together. And that became a great number, staring at him with all his zeros with as many reproachful eyes.

“That’s the way it is with you!” said those eyes. “But you don’t have to try to make it different. You would have to live so terribly frugally to pay off all of this from your salary! … And never beer again? Never again gin?… Ha! Ha! Ha!… No, that’s good! And did you want to feel that dark silence around you every night? And fear every night because of the edge of the forest a deer shouts to its mate? And do you want to know every night that there in that little room two gray oldies smooth out your scant letters with a trembling hand and read them again because you write so rarely and yet they so long for your letters on a white sheet of paper? … that? … And seeing the steaming, smelly kerosene lamp every night, which never gives enough light to make your house cozy? …

What a fool, that’s why you’re an old planter rot! … What are you worried about your debts? … Let them walk to the moon!”…

Then Pieter Klaassen would put the neatly sorted bills in a drawer of his writing table. On top of the bills, he put the paper with the series of numbers … Tomorrow, the day after and many more days after that, new accounts would arrive. New envelopes, which he would throw unopened in this same drawer. Once…. if his bonuses would have been paid…

And then he called Minah or Sarinah. And he made up for what he had lacked that day because A Seng had neglected his duties. And this was the only time that Minah or Sarinah had the opportunity to complain about the exasperating misdeeds of A Seng. And it was also the only time that Pieter Klaassen promptly promised to fire A Seng tomorrow… early tomorrow…

Leave a comment