When the Imperial Chinese Railway Administration was established, director-general Sheng Hsuan-huai was looking for Overseas Chinese to finance a railway line. Sheng summoned Zhang Pi-shih, one of the wealthiest overseas Chinese capitalists, on his way to Hong Kong, to discuss ways and means of raising shares.

Zhang Pi-shih has established a commercial empire in Southeast Asia. His political link with the Qing government and his vast business connections made him the most suitable person to float shares for the Lu-Han line among the Southeast Asian Chinese. Zhang arrived in Shanghai and informed Sheng that the majority of the overseas Chinese in Hong Kong and Southeast Asia were not enthusiastic about the proposed railway, or other railways in north China. Zhang pointed out that they would be interested railways in the south, particularly in the provinces of Kwangtung and Fukien where they were from. Zhang’s pessimism did not discourage Sheng Hsuan-huai from appointing him the man in charge of raising capital in Southeast Asia for the proposed line.

Zhang then returned to Singapore, and the advertisements announcing the sale of public shares in the Lu-Han line appeared in the local Chinese newspapers in Singapore and Malaya in December 1896. How much Zhang and his agents raised among the overseas Chinese is unknown, but it cannot have been much in the end; the bulk of funds for the construction of the railway had to come from foreign loans. This failure reveals that the overseas Chinese were generally indifferent to economic projects undertaken outside the provinces from which they came. Their concern was chiefly for their home districts and provinces.

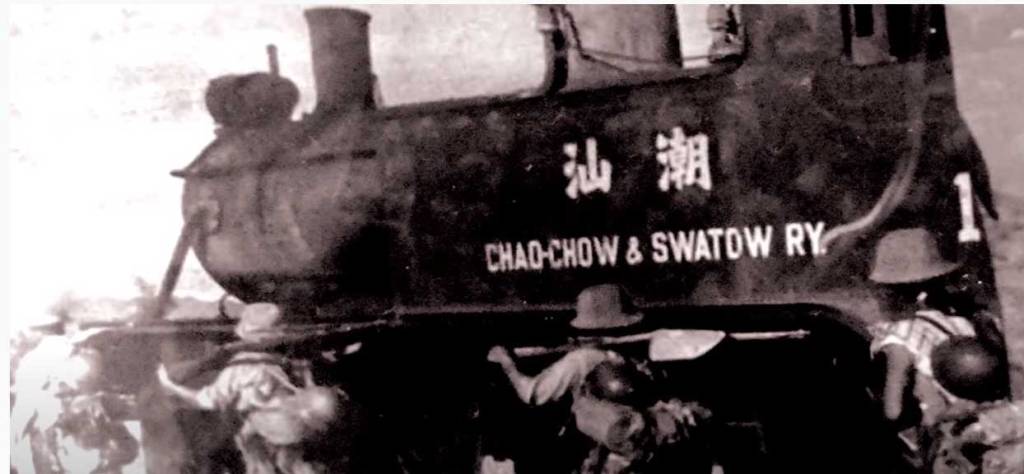

Overseas Chinese large-scale investment in railway construction in China might not have happened if it wasn’t for Zhang Yu-nan (Tjong Yong Hian). Chaochow Railway, which was constructed between 1904 and 1905, set the example for overseas Chinese investors. The railway’s capital came mainly from the Chinese in Southeast Asia, particularly in British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies

Zhang Yu-nan and his brother Tjong A Fie partnered with a Penang businessman, Hsieh Jung-kuang, Chang put together a capital of one million taels. But the capital proved to be inadequate and the Nanyang entrepreneurs had to look elsewhere for support. A Hong Kong millionaire named Wu matched the $500,000 interests held by both Zhang and Hsieh. Lin Li-sheng, one of Taiwan’s leading merchants, invested another $300,000 while a man also named Zhang, reputedly from Siam, added $200,000.

Zhang got full support for the project from the Ministry of Commerce (Shang Pu) in 1903. The proposed Chaochow Railway Company was to receive protection from the provincial government of Kwangtung, which was crucial for any modern enterprise’s success. According to the Chaochow Railway Company charter, which was ratified by the Peking government, it would issue a total of 10,000 shares of stock with a capital investment of 2,000,000 silver dollars. Each shareholder would contribute $200 with an initial payment of $50, and the rest would be paid in two installments. The charter also stipulated that no money would be sought from the government. Zhang Yu-nan and other organizers would provide any balance.

Zhang Yu-nan succeeded Zhang Pi-shih as Vice Council in Penang in 1895. Although the Qing government recognized a Vice Consul as an imperial official, the position belonged to the lowest

stratum of the official hierarchy, and carried little prestige or power vis-a-vis Chinese mandarins. The Vice Consulate in Penang was a very small establishment. Zhang Yu-nan knew his position, and knew how his wealth could enhance it. He used his wealth to acquire more titles, prestige and power from the Qing government. He made contributions to various relief funds in China, and acquired brevet fourth rank with the right to wear second rank feather (hua-ling erh-p’in ting-tai ssu-p’in ch’ing hsien).

In 1902, he moved closer to the centre of Qing power by making a substantial donation of 80,000 taels to the funds of a new Canton high school. He was rewarded with a position of Expectant Fourth Rank Metropolitan Official (Ssu-p’in ching-t’ang hou-pu); and in 1903 he was given an audience by the Empress-Dowager Cixi, a special honour given to promising new officials and talents.

In March 1907 after he had successfully constructed the Chaochow railway, he was awarded a new position of Expectant Third Rank Metropolitan Official. Like many other overseas Chinese of his time, he was a nationalist. He was appalled by the decline of the Qing empire and the weakening of the status of overseas Chinese in sojourning countries.

After initial capital had been raised, the Chaochow Railway Company was officially inaugurated in April I904. Zhang Yu-nan was named the managing director. The shareholders also appointed a Japanese Kennosuke Sato (佐藤謙之助) as chief engineer and awarded the construction contract to a Japanese syndicate. They would like to see a complete Chinese undertaking-from capital to technical expertise and management in pursuing economic nationalism. But there were very few Chinese engineers and even fewer Chinese construction companies which could competently carry out the job. The choice of the Japanese engineer and construction firm in preference to Europeans was probably influenced by Lin Li-sheng, the Taiwanese shareholder. He was later accused (by some Chinese students studying in Japan) of being an agent for Japanese capital.

Soon after assuming the Chaochow Railway Company’s managing directorship, Zhang Yu-nan seems to have sensed problems ahead. Two likely difficulties were opposition by the gentry and foreign intervention. Zhang must have heard of the fate of China’s first railway (from Wusung to Shanghai), which was dismantled owing to strong gentry opposition. The gentry’s deep influence in Chinese society at the local level was well known, and must have been known to Zhang; any mishandling of the issue could lead to a riot, or at worst to the failure of the undertaking. Although Zhang had obtained the support of the central government, which instructed the province Kwangtung and the local government of the Chaochow prefecture to render protection if deemed necessary, he was not sure whether the instruction had a real effect. Even if it had, it could offend the local gentry and put the project into an awkward position between the Mandarins and gentry.

To ensure a smooth path, the gentry’s support must be sought. Zhang Yu-nan shrewdly appointed a powerful member of the gentry named Hsiao Ch’ih-shan as the Chaochow Railway Company’s general manager. Hsiao held a Third Rank with feather, and his holding of a position of Expectant Circuit of Northern Chaochow indicates his wealth and influence at local level. Zhang Yu-nan seems to have expected some difficulties in getting Hsiao to persuade his fellow gentry to support the proposed railway. In an open letter to Hsiao, Zhang Yu-nan emphasized that the project was undertaken in the interests of the nation as well as for the benefit of local merchants and ordinary people; he further stressed that the project was intended to ward off foreign control of the Chinese economy. Apart from appealing to Hsiao’s patriotism, Zhang tried to persuade Hsiao to come to his aid because of the long-standing friendship and their common concern for the welfare of their home province, Kwangtung. Hsiao’s eventual acceptance of the job went some way toward guaranteeing the support of local gentry for the new venture.

The second problematic area that Zhang Yu-nan had identified was foreign intervention. As imperialism tightened its grip on the Chinese economy and competition among the Powers intensified, the railway issue became the focus of the concessions politics, for it offered the key to the control of the economy and politics of the concession areas. The Powers jealously guarded what they had acquired from China, and also watched the moves of others. Despite their rivalry, they shared common anxiety about any Chinese move that might jeopardize China’s interests. A move like the proposed construction of the Chaochow Railway with Chinese capital would arouse their deep concern, and might even invite their intervention. Zhang Yu-nan seems to have realized this danger.

Before actual construction work was started, he held a dinner party to entertain foreign consuls and

consul-generals in Swatow on 20 May 1904. This was intended to cultivate good relationships with the foreign diplomats who would have a role to play in determining the western powers’ attitude towards the new undertaking. Zhang may have briefed them about the project and assured them that it was not designed to jeopardize the interests of the powers in China, but merely expressed the concern and love of overseas Chinese for their home province.

Early reports indicated a bright future for the project. Surveying was started, land was acquired and the local gentry were on the whole cooperative. There were occasional protests but Zhang adopted a policy of compromise and simply changed the route wherever possible to meet the local demands. The preliminary works were completed in August 1904, and actual construction commenced in the following month. A few months later, trouble broke out where Zhang Yu-nan had not anticipated it. The Japanese construction team offended local sentiment. In a broader sense, it was a conflict between Japanese imperialism and emerging China nationalism. Even before construction began in

September I904, anti-Japanese feeling had been gradually built up. A rumour spread that the Japanese were attempting to control the railway by purchasing shares through some overseas Chinese merchants. It was reported that students of Chaochow prefecture who studied in Japan held a meeting to discuss the matter, and they sent petitions to Zhang Yu-nan, Zhang Pi-shih and other dignitaries who were directly associated with the railway to warn them about the Japanese intention. Local inhabitants who were fearful of their ancestors’ spirits being disturbed and were annoyed by foreigners’ presence took a militant stand, and their relations with the Japanese construction team became tense. Two Japanese workmen were murdered in the An Village. The Japanese responded with some harsh demands. There threatened to be a crisis of national importance. Near-riot conditions followed the shootings and the Viceroy of Kwangtung and Kwangsi had to send troops to put down the disturbance. The Japanese demanded the punishment of the killers, and compensation for the families of the victims and for the damage done to Japanese property. The Japanese government threatened to use force if the demands were not met.

The incident put Zhang Yu-nan in a precarious position. To comply with the Japanese demands would be seen as a cowardly move and would heighten anti-Japanese sentiment, but to ignore the Japanese demands might spark off a national crisis. Like a man walking on a tight-rope, he attempted to extricate the issue from international politics. He represented to the Japanese government that since the Chaochow Railway was a private enterprise and had signed a contract with a Japanese company, the matter was basically a dispute between businessmen, and the Japanese government had no reason to interfere.

He was prepared only to pay a sum of $10,000 for the death of the two workmen following the limit of liability fixed in the agreement with the Japanese company. But the Ministry of Commerce quickly recognized the potential explosiveness of the incident in ‘concession politics’. Like many other incidents of this kind, it could have led to direct Japanese military intervention and resulted in controlling the entire Kwangtung province. The Ministry ordered the Chaochow Railway Company to pay an indemnity of $210,000 to settle the issue. At that time, Japan was preoccupied with the ongoing Russo-Japanese war, and it accepted the compensation and dropped the matter.

The Chaochow railroad was completed after two years’ construction, and it began operation in November 1906. It was on 24 miles (39 km) of standard gauge, and its total cost was estimated to have exceeded $3,000,000. The railroad started from the west gate of Chaochow city and terminated at Hsia Ling of Swatow. There were six stations in all, and the same number of trains travelled the distance daily, three on the northward run and three on the return trip to Swatow.

I-Chi, a.k.a. Yee Kai (Yixi; 意溪)

Chao-chow (Chaochou; 潮州)

Feng Chi, a.k.a. Pang-Khoi or Fong Kai (Feng- xi; 楓溪; 枫溪)

Fou Yang, a.k.a. Phuie or Fow Yong (Fuyang; 浮洋)

Kuan Chow (Guanchao; 鹳巢)

Tsai Tang, a.k.a. Tsua Tung (Cai Tang; 彩塘)

E- Bue (Hua-mei; 華美; 华美)

Ampow, a.k.a. Am pou (Anbu; 庵埠)

Swatow (Shantou; 汕頭; 汕头)

Six trains travelled the distance daily, three on the northward run and three on the return trip to Swatow. A band from the German crusier Jaguar was reported to have played in the very first train giving a strange twist to the line’s basic anti-imperialist theme.

Many observers were pessimistic about the railroad. Oversized administration and an ambitious training scheme increased the expenditure of the Company, while keen competition from cheaper steamer services kept the revenue too low to permit payment of dividends. This was not, however, strictly the result of poor planning.

In 1908, works began to extend the line further inland to join a new railroad from Canton to Amoy which was planned by Zhang Pi-shih. But the Canton-Amoy line was never constructed, and thus left the Chaochow railroad a branch without a trunk. Attempts were later made to extend the line to Canton as to make it economically viable, but again they were of no avail. Thus the first Chinese railway with substantial overseas Chinese capital had no great commercial success.

The Chaochow Railway nevertheless had some psychological and political success. Psychologically, it brought self-confidence and national pride to all Chinese. Before the commencement of the project, the attention of Chinese from different circles was drawn to it, and it was regarded as a test case. Its successful completion excited many Chinese and convinced them that Chinese were capable of building a modern railway. It set an example for modern private enterprises run and supervised solely by merchants. The new formula ‘merchant-run enterprise’ (shang-pan) in replacement of the old formula of ‘Official Supervision and Merchant Management’ (Kuan-tu shang-pan) was proved workable. It also set an example for the investment of overseas Chinese capital in railway development in China. In retrospect, the self-confidence generated by the Chaochow Railway’s success was important for Chinese capitalists, at home and abroad, who undertook similar projects in later periods. The national pride that emerged was used as an important symbol for the development of economic nationalism.

Zhang Yu-nan made a name in Chinese history because of his involvement in the Chaochow Railway, while the Chaochow Railway made a name in Chinese economic history because of overseas Chinese

investment. But both Zhang and the railway were economically insignificant at the time. This episode illustrated the point that overseas Chinese capital was inadequate to support any major undertaking, and could not take the place of foreign capital. It could only play a supplementary role in China’s early industrialization. However, Zhang’s motives in the construction of the railway typified the desire and hope of many overseas Chinese; while the difficulties and the limited success of the railway exemplified the fate of many overseas Chinese capitalists in their involvements in the late Qing economic modernization.

Initially, the railway’s senior operations staff, including the drivers and guards, were all Japanese employees. This was eventually taken over by Chinese National Railways in the 1920s. The railway company imported three 2-6-2 tank locomotives from the American Locomotive Company (Brooks plant) and 24 carriages of corridor plan were manufactured in Japan.

Chang Yu-Nan and the Chaochow Railway (1904-1908): A Case Study of Overseas Chinese

Involvement in China’s Modern Enterprise.

Yen Ching-Hwang. Modern Asian Studies , 1984, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1984), pp. 119-135

Leave a comment