After 1900, some Officials for Chinese Affairs became involved in other coolie matters, when they were charged with the inspection of labour conditions in the Indies and the accompaniment of direct repatriation of coolies. When Hoetink returned to Batavia in 1900, he was temporarily placed at the disposal of the Director of Justice to fulfil special tasks. During the following years, he was charged to investigate the working of the Coolie Ordinance in a number of mines and plantations in the Outer Possessions, where most workers were Chinese. In the regulations for the Officials for Chinese Affairs of 1896, the inspection of Chinese labour conditions for the regional government (Resident) had already been defined as one of their tasks (article V).

The first Coolie Ordinance for Deli dated from 1880 and was revised in 1889, regulating the rights and obligations of workers and employers, but actually rather consolidating the exploitation of coolies than warranting their rights, in particular because of the system of poenale sanctie (indentured labour): the prohibition to leave the premises and the corporal punishment for doing so.

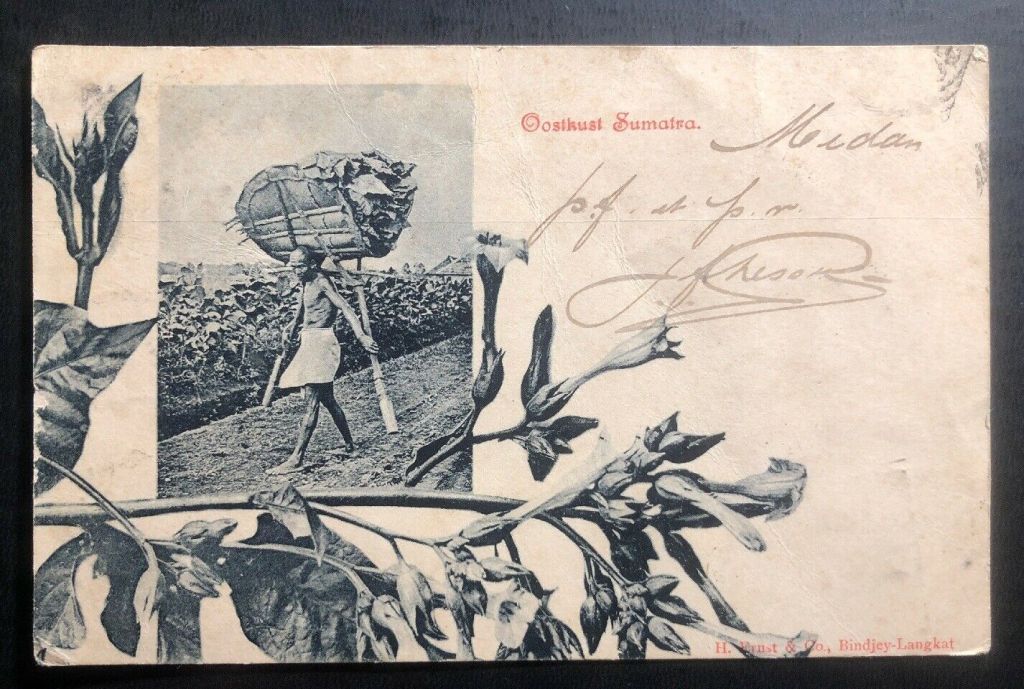

In 1900–3 Hoetink visited mines and plantations on Sumatra, Borneo, Banka, Billiton, and Singkep, and wrote reports about them. Labour conditions were a hot item in those years. In 1902, the lawyer J. van den Brand published a pamphlet criticising the enormous profits earned by the planters in Deli, entitled The Millions from Deli (De millioenen uit Deli). Basing himself on Christian ethics, he exposed the exploitation and abuse of Chinese and Javanese coolies in Deli. This pamphlet caused a shock in both the Netherlands and the Indies, and the next year the public prosecutor J.L.T. Rhemrev, a Eurasian, was sent from Batavia to Medan to investigate possible crimes. Although in his report he pointed out many flaws in Van den Brand’s writings, showing that the latter was exaggerating, his conclusions were similar. He proposed several means to improve the situation, such as to appoint special officials to supervise the observance of the Coolie Ordinance, and the establishment of a Raad van Justitie in Medan – until then, all cases involving Europeans had been tried (or not tried) in faraway Batavia.

The Director of Justice had already proposed the establishment of a labour inspector in 1902, and he evidently had a candidate in mind: Hoetink. But Hoetink had made known in March 1903 that he was not interested. In March 1903, after two and a half years of working for the Department of Justice, Hoetink was given a year of leave to the Netherlands because of long service, as from 7 April 1903.

A year later, when he returned to Batavia, on 30 April 1904 Hoetink was charged with revising the Coolie Ordinance. He already knew about this charge before he left the Netherlands. Hoetink finished his first draft on 8 July 1904, and the second on 12 January 1905, the day after he had received new comments from the Deli Planters Committee. Both versions were printed. Possibly in preparation for more inspections by Officials for Chinese Affairs, article V of the regulation of their functions was expanded in January 1904 so that it also included the inspection of the labour conditions of the native population.

In the meantime, Hoetink was again offered the position of labour inspector on the East Coast of Sumatra. Now he was ready to accept on two conditions: the position should not be made subservient to the Resident of Deli, and he needed at least two assistant inspectors. Realising that the local planters would consider him a snooper (dwarskijker) – just as Schlegel had written thirty years before – he was well aware of the difficulty of the position.133 On 24 July 1904, Hoetink was appointed temporary Inspector of Labour on the East Coast of Sumatra, becoming a High Official (hoofdambtenaar) at f 1,200 monthly,134 a rise in salary of 50%.

This appointment was all the more justifiable as he had passed the Higher Officials Examination in 1893. At this moment Hoetink’s career as Official for Chinese Affairs ended. The tasks of the inspector were defined as direct supervision of the regulation on mutual rights and obligations of employers and employees, regular visits to enterprises, checking the local conditions and receiving complaints, and reporting and making proposals.

Van den Brand’s pamphlets and Rhemrev’s inspection results had not only shocked the Dutch general public, leading to debates in Parliament, but also the Deli planters. They were accustomed to being left to their own devices, lived during the acme of liberal entrepreneurship, and were not used to any government interference. It was a wise choice of the government to charge Hoetink with the task of becoming the first Labour Inspector, since he knew the local situation and had tact and understanding. In Hoetink’s draft Coolie Ordinance, the obligations of employers were increased and the poenale sanctie was abolished, but as long as the new ordinance had not been proclaimed, Hoetink could do no more than to urge the employers to comply. Still, many realised they had no alternative and respected some of the new rules, such as the new labour contracts. But when after one year the introduction of the new ordinance was postponed for a long time, this was a blow for the Labour Inspection. Now even more, Hoetink could only use his moral powers to ameliorate the labour conditions. “All I can do is talk,” he often said. But in a creative way he was more than able to do so, upright in his words and knowing the practical demands of the enterprises. He only wanted “some humanity towards the smallest of small people, a little heart” (wat menschelijkheid … jegens de kleinste der kleine luyden; wat hart).

In his farewell speech he said that he constantly asked the planters to see the workers in another light, not to consider them as “contract animals” (contract dieren) but as human beings deserving a worthy human existence. According to newspaper reports, he achieved many successes. Not only were the new-style labour contracts accepted; living and medical conditions improved as well, and schools were established for (native) coolie children, which had been completely unimaginable until recently. However, still much more needed to be done and in the end the schooling project became a failure.

Typical of Hoetink’s creative talent was his combining the interests of the planters with that of the coolies, for example in his initiative to found a Chinese Remittance Bank, the Tong Sian Kiok 同善局 in June 1905. This was a nonprofit foundation helping to send the coolies’ savings and letters to their families in China. The bank was established in cooperation with the majoor Tsiong Yong Hian and the kapitein Tsiong A Fie, both popular Hakka officers. An attractive booklet containing its regulations was published in Chinese. In a newspaper article Hoetink explained that this bank could prevent the coolies’ losing their savings to their foremen, to gambling and to opium, and at the same time promote emigration, since it would strengthen the opinion in Southern China that Deli was not a bad place to work. When Hoetink left a year later, this bank was mentioned as one of his achievements, so it must have had some success. In 1907, the majoor and kapitein and other Chinese founded the Deli Bank, which could deliver similar services, but was in operation only for a few months.

Hoetink wrote about this initiative in “Eene Chineesche Remise-Bank.” (De Sumatra Post, 16 June 1905). The purpose of this was to facilitate correspondence and remittances and thereby also to promote emigration to Deli.

A similar measure was that at the end of the field season (veldtijd) in 1905, the impressive number of 1,091 Chinese contract labourers were directly repatriated at the planters’ expense, taking along a total amount of $95,000 (on the average $87 per person). Such measures had also been taken earlier, for instance in 1888.141 Direct repatriation as a means to promote emigration was related to the so-called lau-kheh recruitment.

After a few years of work, in the Outer Possessions a sinkheh “new guest” (orang baru) would be called a laukheh 老客, “old guest” (orang lama). Sometimes groups of lau-kheh were charged to urge their compatriots in their home villages to come to work in the Indies. This method was in particular successful on Billiton.

In 1905 no “rows” took place among the Chinese, owing to the tactful functioning of the Labour Inspector Hoetink, who was praised for not acting as an inquisitor (like Rhemrev), but as an arbiter. When after two years Hoetink was at his own request discharged and obtained a pension after 28 years of government service, he stated in his farewell speech that he looked back with satisfaction on his achievements as Labour Inspector. Resident J. Ballot, Assistant-Resident E.L.M. Kühr (Borel’s brother-in-law), and others also expressed their great appreciation.After Hoetink left, his two assistants also soon left the service.

Two years later, in June 1908, a Labour and Immigration Inspection covering all of the Netherlands Indies was established. A new version of the Coolie Ordinance for the East Coast of Sumatra would finally be proclaimed ten years later, on 22 June 1915, replacing the 1889 version. But there was still a long way to go, since for the planters the poenale sanctie remained indispensable. This measure was finally abolished in Deli in 1931, after the threat of a boycott of Deli tobacco by the United States. Moreover, as a result of the financial crisis it had become easy to obtain labour, which made the poenale sanctie superfluous. In 1941 it was abolished in all of the Netherlands Indies.

Some other sinologists also occupied themselves with coolie matters. For instance, Borel performed an inspection of the tin mines in Singkep in 1904 and wrote a critical report. According to him, this led to his transfer to Makassar, which he could only avoid by requesting leave to the Netherlands. More than twenty years later he explained in a newspaper article what had happened. When he performed inspections accompanied by the head administrator and the fearful mandurs (foremen), all seemed in perfect order, but when he returned at night, speaking Chinese with the coolies, he discovered the most gruesome abuses and even crimes. But at the time such matters could only be covered up, and that happened with his report also.

In April 1905, Van de Stadt was sent to Singapore, Pakhoi (Beihai), and other places in China to investigate the situation of recruitment of coolies for Banka and to arrange for a regular supply of workers for the Banka tin mines, having a mandate to recruit 6,000 coolies. He stayed in China until the end of the year, but did not achieve any success. The mission was observed with concern by J. Stecher of the Deli-Maatschappij, who feared that competition between Deli and Banka would drive up the costs,151 as had happened in the past before the Deli planters decided to cooperate in 1888. After Van de Stadt’s failure, from 1906 on several shipments of coolies were sent directly at the government’s expense from Banka to Southern China.

As with the gratis repatriation of coolies from Deli in 1905, the main purpose was to promote emigration. In this manner the pitfalls of gambling, opium and prostitution in Singapore could be avoided, since that town was the unavoidable stopover for remigrating coolies from Banka. On three shipments the coolies were accompanied by Official for Chinese Affairs Thijssen, who afterwards wrote detailed reports. The reason why Thijssen, then stationed in Surabaya, was sent to China was probably that on Banka no Official for Chinese Affairs was available at the time. The first mission was announced in De Sumatra Post under the title: “Good Things from Banka.” Thijssen was to leave within one month after Chinese New Year (25 January 1906), the date of expiration of the contracts, and would be accompanied by two European doctors. This time, according to the newspaper, for a change the government was not tight-fisted, and also paid attention to details. For instance, dangerous overland travel with their savings on Banka, where robbers were rampant during the season when the Chinese coolies returned home, was avoided since the coolies could embark in several harbours on the island.

While the official reason for the first shipment was to promote the recruitment of miners for Banka in China, since Van de Stadt’s mission had been unsuccessful, it was also meant to protect the coolies, who often lost their savings in Singapore, from becoming prey to the coolie crimps. Thijssen’s detailed first report was published in several newspapers and summarised in others. With two ships of the Ned.-Indische Paketvaart Maatschappij, in total 683 miners were repatriated, being paid on arrival a total sum of f 47,281.50, on the average f 169 per person. When these savings were paid at the ports of arrival Hoihow (Haikou) and Pakhoi (Beihai), but even in Hong Kong, many local Chinese were surprised that coolies could earn such large amounts of money with simple labour. Thijssen described how he took good care of the coolies, solving various personal problems, even advancing their savings from his own pocket for about ten coolies who had requested the wrong harbour of disembarkation. He justified this in his report by noting that the repatriation was intended to benefit the coolies. In conclusion, he also made a lot of other suggestions for improvement.

Two years later, on 2 January 1908, he was in a similar manner temporarily put at the disposal of the Resident of Banka in order to arrange the repatriation to South China of miners whose contract ended in February. He was to leave Batavia on 18 January after consultation with the Director of the soonto-be-established Department of Government Enterprises (Gouvernementsbedrijven).154 No report of this mission could be found. The next year, in January and February 1909, he escorted another repatriation of 1,139 workers from Banka to Southern China.155 This time Thijssen’s report was not published in the newspapers, but it has survived in Borel’s archive.156 The coolies were now transported on a ship of the Java–China–Japan Lijn, the Tjibodos, to Hoihow, Pakhoi and Swatow, where they received in total f 67,644.80, on the average f 59 per person. Now the situation had changed and the government had become tight-fisted again. The food was provided by a (Chinese?) comprador, probably at the cheapest rate. Before the ship left Banka, the Resident came on board and, after trying the food, “expressed in strong terms his dissatisfaction with this ‘filth’.” During the journey, Thijssen protested several times, fully supported by the captain, but he could only achieve slight improvements. Afterwards, Borel wrote on the first page: “N.B. The last time that an Official for Chinese Affairs accompanied them. From now on they do without,” and later in the margin: “Nowadays no Official for Chinese Affairs accompanies them. Too ‘troublesome,’ probably! H.B.” No further repatriations escorted by Officials for Chinese Affairs are known.

Following the reports on abuses in Deli by Van den Brand and Rhemrev, Hoetink became the first (temporary) Labour Inspector on the East Coast of Sumatra; he combined an understanding of the interests of the enterprises with sympathy for the coolies. Thijssen’s assignments were probably also intended to mitigate criticism of the coolie system. From now on, ideas about labour relations were changing fast in society.De Groot seems later not to have felt so proud of his accomplishments in this respect, and in the 1980s Hoetink was (unjustly) accused by a modern scholar of “being on the side of” the planters only. Actually, by the standards of the time the efforts of both achieved fine results under extremely difficult circumstance

Leave a comment