Medan was first developed with the establishment of Deli Maatschappij headquarter on the east bank of the Deli river the confluence with the Babura. At the time of commissioning in 1870, still an extremely austere construction of wood and atap. In the following years, it also served as a pesanggrahan or guest house, hospital, church, banquet hall and administrator’s house. It stood by itself, and a short distance away on the river was a Malay kampong called Medan Poetri . A little southwards a second kampong called Kesawan.

In 1872 the Batak uprising in Deli led to the army of a KNIL military department, for which an encampment of wooden sheds was built just south of the head office. It remained in use until the mid-1890s, when the garrison moved to a new one encampment on Polonia on the other side of the Deli River, north-west of Deli Maatschappij. Shortly after 1872, the small fortress of Medan, the Redoute Polonia, which in later years would, among other things, serve as a soldier warehouse and hospital. In the last two years before the turn of the century, it became the Garrison of Medan. Incidentally commanded by Major R. MacLeod, whose wife Margaretha MacLeod-Zelle, whom in the following decade in Europe, would be celebrated as the ‘oriental’ dancer Mata Hari.

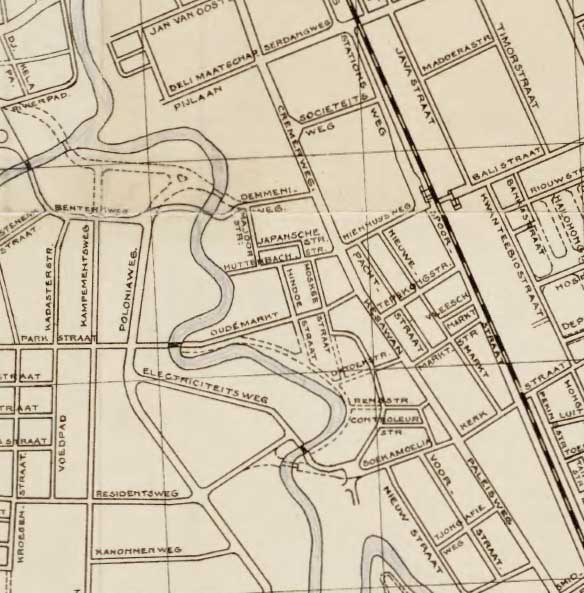

About 300 m east of the office of the Deli-Maatschappij in the 1870s, a tobacco lying fallow was still used. Circa 1880 this was provided with roads all around, after which this Esplanade in the next years became the place where the first other European buildings were established. Explanade has a wide area, about 175 m x 275 m.

On the south side, the small hotel De Vink was opened in 1884, predecessor of the Grand Hotel Medan, which at that time was still nicknamed ‘De Pijpenla’ (pipe box). This is also where the association ‘Gezelligheid in Deli’ organized theater and music performances.

The colonial club ‘Sociëteit de Witte’ was founded in 1879, a provisional accommodation was built in 1882. Later moved to the new building in 1887 on the other side of the Esplanade (next to the post office).

The Deli Maatschappij founded a railway company the ‘Deli Spoorweg Maatschappij’ in

1883 and in 1885 the railway between Medan and Labuan-Deli was inaugurated. The railway

station was located on the western side of the Esplanade.

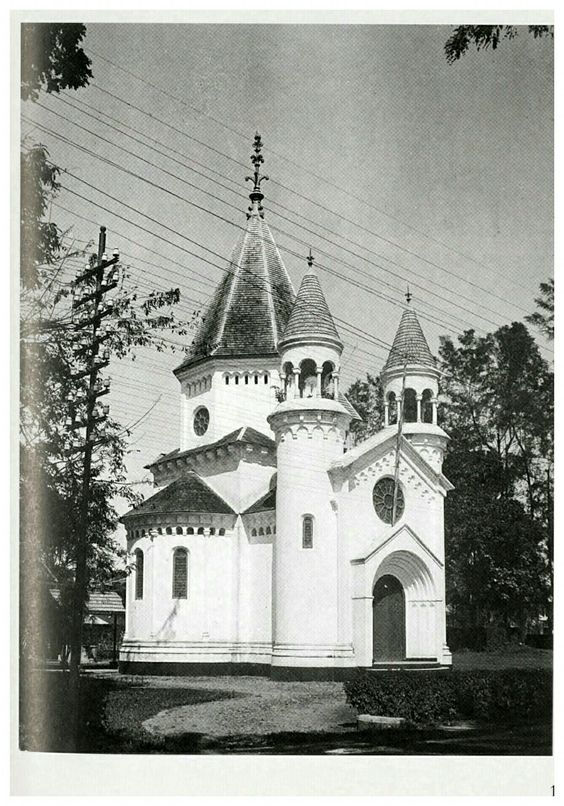

Next, the Western side of the Esplanade was filled with permanent buildings. In 1887, the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China opened an agency next to the Grand Hotel Medan. The following year, the Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij moved into a building on the west side of the square, on the corner with the later one Huttenbachstraat. The most striking building to be built here was undoubtedly in 1900 the new church of the Protestant Congregation of Medan, a place of worship in German-like neo-Romanesque style on an almost circular ground plan. But it had to make way for construction again in the 1920s for the new building of Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij.

The Sultan of Deli, Ma’amoen al Rasjid Perkasa Alam Sjah moved its palace from Labuan-Deli to Medan. In 1887, he built the palace Istana Maaimoon designed by the Italian architect Ferrari, on the west bank of the Deli River and it was finished in 1891. The new palace showed the remarkable progress in his financial position, gained by concession contracts and land taxes.

South-west of the Sultan’s palace, the great mosque (mesjid raya) was designed by the architect Dingemans in a Moroccan style with stained glass windows and was built in 1906.

Following the policy of decentralization, a region council ‘de Afdeelingsraad van Deli’ was founded in the year 1906, only to be abolished in 1909, when Medan obtained the status of independent municipality. In 1907, a reform the currency on the north-east coast of Sumatra was done. The British colonial Straits dollar was banned and the Dutch-Indies guilder was introduced. In connection with the currency purification, in the years 1907-1909, De Javasche Bank established an agency in Medan, with a specially-designed building on the corner of the Esplanade. The design was granted to Ch M Boon, a construction engineer of Deli Maatschappij. Once completed, however, it was rejected by the central management of the bank. The Afdeelingsraad van Deli purchased the building in early 1909 as the town hall of the newly to be established municipality of Medan. Tjong A Fie, the Majoor der Chinezen, presented a clock for the townhall in 1912.

The Javasche Bank asked Amsterdam architect Eduard Cuypers to design a new bank building, which was also completed in 1909. The building was also located at the Westside of

the Esplanade between the townhall and Hotel de Boer. In 1909, Eduard Cuypers started an office in Batavia in collaboration with M.J.Hulswit and architect A.A.Fermont joined in 1910. The team ‘Hulswit- Fermont, Batavia and Cuypers, Amsterdam’ became the most successful architects in pre-war Indonesia.

The post office was designed by the architect S Snuyf from the Department of Civil Works, located on the northwest corner of the Esplanade in 1898. It was completed in 1909. Hotel De Boer opened in 1910, located just northwest of the Esplanade.

In 1910, northwest of the Esplanade, the new headquarter of the Deli Maatschappij was completed by architect D. Berendse.

Kampung Kesawan

A remarkable development made the kampong Kesawan south of the Esplanade which originally was inhabited by the Malays and Indians. Due to the large influx of Chinese from Malacca and later from China, they established a strong foot. At the main road, tens of Chinese toko’s (shops) were established. These shop houses had only one storey with the living area in the rear and the commercial area in the front. The construction techniques of the shop houses and warehouses were based on locally available materials, wood and atap roofs, combined with Chinese architectural influences.

Around 1880, Kesawan became Medan’s Chinese shopping and craft district par excellence. Later, European retailers and other private companies started to settled. The prestige of the district was rather uneventful for a long time as it was dominated by small timber houses and shops. At the beginning of 1899, however, a huge fire laid a large part of this southern city between the Esplanade and Soekamoelia, after which only stone buildings were still allowed. The rebuilding followed within a few years, mainly through project development of entire street blocks simultaneously by Chinese entrepreneurs such as the Tjong brothers. This is how the striking unity in the street scene, with two-level Chinese shops. The ground floor is for commercial business, and upstairs serve as living area. This rumah toko is a characteristic retained until current.

The first decade after the turn of the century, the expansion of the Chinese quarter on the east of the railway line also began in a similar pattern to Deli Toea. Lots of new street names – Hongkong Street, Hakkastraat, Cantonstraat, etc – referred to the home country of the residents. In the case of Luitenantsweg and Kapiteinsweg, are great members of the Chinese community who financed the construction of this part of Medan.

Further north along the Serdangweg, in the vicinity of the first DSM head office, completed in the last years of the 19th century in (1888) the so-called Serdang-kwartier, a residential area for mainly European employees of the Delispoor. Even more east, in line with the Hotelweg – later called Nienhuysweg – became the second half of the eighties racecourse of the Deli Ren Vereenigmg, which in 1894 belonged to the Deli sultan. According to Justus van Maunk, himself an enthusiastic practitioner of the Cycling sport blown over Europe, expanded with a cycling track between the racecourse and the railway line also stood until shortly after the turn of the century.

The Medan country residence of the sultan of Serdang, whose court for the furnace, however, entered Loeboek Fakani. The main street of the same name in the Kesawan district, between the Esplanade and the South connecting Paleisweg to the Kota Masoem, formed after the fire of 1899 became an exception to the uniformity.

The Kesawan’s architectural style gradually Medan’s luxury shopping street par excellence, where the range offered by the retailers increasingly focused on the needs of the European urban population and especially the planters of the surrounding companies. The most famous European department store – although according to Justus van Maunk not much more than a ‘large, spacious toko’. The company Katz & Co was here around 1900. The main Chinese competitor Seng Hap stunned ‘tout Medan’ in 1903 by the rebuilding his shop in the shape of an imposing Roman temple, which today is considered one of the most striking elements of the bequest colonial architecture in the city.

The area west from Kesawan to the Deli-river also acquired a predominantly Chinese character in the last decades of the last century, although certain street names indicated -Japanese Street, Hindoestraat – that here also a significant minority of other ‘Strange Oosterlingen ‘lived. On the south side of this zone between shopping street, several government agencies were established, such as at the western end from Sukamoelia the prison, the Landraad, the first police barracks, the bureau of Civil Public Works and, since 1876.

The Assistant-Resident in Medan was established in in 1879. The official residence which also served as the residence office was designed as a Victorian renaissance style, completed in 1898 on the western side of the Deli River. That new building was an almost faithful copy of the then post office in Singapore build in 1874. It was no longer located adjacent to the buildings on the east bank of the Deli-river, but on the other side, south of the existing Polonia military encampment.

This was the start for the direction in which the European districts of Medan would mainly develop further in later decades existing quarters. In addition to the DSM neighborhood on Serdangweg, also the employee neighborhood around the head office of the Deli Maatschappij and the district between the Kota Masoem and the Kerkstraat / Soekamoelia, barely offered after ca 1910 more expandability on any scale. Just then with the novice boom in the new rubber culture increasing numbers of Europeans to Medan. However, it would not be until 1918 that the municipality Medan came to a final agreement with the Deli Maatschappij about the making company land available for housing, and the relocation of the municipal boundaries southern and western the construction of Polonia.

However insignificant it may have been started around 1870, three decades later Medan has already become a real city, whose prestige despite its unmistakable ‘boomtown’ character and all its imperfections to impress newcomers.

In 1897 the writer Justus van Maunk, his well-known Indies travel book. Impressions of a ‘forum’ about his visit on the capital of Sumatra’s East coast ‘Medan, immediately makes an impression. A place full of vigorously cheerful life. Medan would quite rightly be “the tobacco city” because in fact she owes her unfitness and always to the tobacco increasing prosperity. Less than thirty years ago, Medan was a small, insignificant, so-called fortified kampong and only when the tobacco plantations expand more and more, that kampong, thaw her favorable location on the Deli River and the Baboera designated for this purpose, suddenly and beautifully, spaciously laid out, almost bearing a Western character, where now established the great establishments and offices of the Deli Society. One can see from the neatly tidy well-built and lavishly furnished houses, that Medan need not look upon the coin to understand it, that money is round and must roll and that comfort and leisure can be combined well are with tireless and hard work.

In almost all areas, Medan’s early development was strongly influenced by the Overwal, Deli commonly used term for the British territories on Malacca, i.e. the Straits Settlements and the British supreme authority. standing Malay principalities on the peninsula. Until about 1890, for example, almost the entire Deli export was carried through Penang and Singapore to Europe and America, while conversely Deli western import goods m this period almost exclusively by or on commission from British and Chinese merchants of the overalls were offered. So the currencies used there, the British trade dollar and later the Straits dollar, generally in circulation as a means of payment on the East coast, in addition to the Dutch-Indian guilder was permitted as legal domestic tender. This happened partly against the Deli planters’ community, where until then the gradual depreciation of the dollar – the guilder had a gold, the Straits dollar a silver cover standard – had managed to make an extra profit by paying the coolie wages in ‘softer’ dollars. In addition, several British plantation companies settled in Deli soon after its initial opening, followed in the 1880s by the agencies of commercial and credit banks such as the aforementioned Chartered Bank. of India, Australia and China, Brown & Co. Initially through a representation by the latter, the Mercantile Bank of India, London & China.

The most influential of these companies became without a doubt Harrisons & Crossfield Ltd, which became mainly active in the rubber culture as a general trading house importer and agency holder for a number of renowned UK shipping companies and insurance banks and for Imperial Airways. Harrisons & Crosfields Medan headquarters on the corner of the Kesawan and the Esplanade, the so-called Juliana House from 1909, was converted into its architecture is therefore a pure example of Anglo-Saxon functionalism. Because of its impressive metropolitan appearance at the time would like to be seen as representative of the European business life in Deli.

The nearby agency of De Javasche Bank and the Medan town hall also exhibit clearly English features in their architectural style, although the designs here catch on partly back to an older, more generally accepted Indie pseudo-classicism. In daily life the effect of the British influence during the in the previous decades around the turn of the century became noticeable, especially among the European population group, by a characteristic ‘Delian’ language. Many Dutch and especially Malay words and expressions had been replaced by colonial English synonyms. To a native house servant here was called boy instead of djongos, the madam the house was not called njonya but mem (of memsahib), and a little company soon became an estate. Perhaps the most controversial aspect of it the raided lifestyle in Deli was the use of the so-called ‘hongkong’, meaning the well-known or infamous Chinese ricksha. This mode of transport was then known in Penang, Singapore. Hong Kong and elsewhere in the British colonial world of South and East Asia are widely accepted. In the Dutch East Indies it was generally regarded as ‘unethical’ in European circles and outside Medan and some other places on the East coast, ‘hongkong’ never became established.

As a result of the land transaction in 1919, the municipality gained the former tobacco plantation ‘Polonia’ to the south-west of the Deli Maatschappij. In the Polonia extension they built the garden city of Medan. The boundaries of the Polonia area were formed on the west by the Deli River and on the east by the Barbura River. On the south, the Medan-airport, Polonia, was inaugurated in 1928. The funds necessary -for the development of the airport were raised in the old- fashioned Medan tradition by private initiative, in this case a joint venture of the societies of tobacco and rubber planters (D.P.V and A.V.R.O.S).

The important north-south road Poloniaweg (Jl.Iman Bonjol) had already been in use from around 1870 as a transport road between the tobacco plantation Polonia and the headquarters of the Deli Maatschappij for shipping of the tobacco by prau-transport to Labuan-Deli.

Apart from this historical transport road, the designed urban grid in Polonia featured a new important north-south artery, the Manggalaan/ Jl.Diponegoro which was connected in the South with the east-west road, the Sultansweg/ Jl.Jend.Sudirman and in the north with the open field in front of the complex of the Court of Justice (1914); which was used until the thirties as sports ground for playing football and tennis.

Except for a few secondary roads, the neighbourhoods were located on the east-west street

plans. Around 1930, new development activities started to the south of the Sultansweg/ Jl.Jend.Sudirman. Due to the economic depression of the thirties, the building-activities made slow progress. Calling to mind the urban layout of southern Polonia (Nieuw Polonia), one can recognize a continuation of the northern area. Until the 1950s, the entire Polonia area functioned as a typical European neighbourhood.

The Esplanade, until 1927, the northern side, the large open area in the middle of the Esplanade, functioned as a sports ground. The first movies were showed in a barrack on the Esplanade; this was the initiative of a former planter, who owned three modern cinemas in the 1930s. After 1927, the heart of the Esplanade was finally put to use as a park.

Direct immigration of Chinese contract workers

A maze of obstacles resembles the terrain over which the efforts of the old leaders of the tobacco culture to reach an insured regular imports of skilled workers, in the first place from Chinese farmers without whose efforts no valuable wrapper. It has already been mentioned how the shortages of agricultural workers from 1879 on main reason for the foundation of the Deli Planters Vereeniging.

The continuing expansion of the tobacco culture forced the companies to take more joint action when contracting overseas. Following on from existing practice, the focus was initially mainly on Malacca, where every year tens of thousands of penniless ‘singkeh’ (newcomers) as emigrants arrived from southern China. Some of this ‘living material’, such as Dr. Broersma still wanted to express himself in 1919, quickly found work in entrepreneurial agriculture and the tin mines on Malacca. But a larger percentage was taken in by coolie brokers and often recruited under physical coercion or deliberate debt. Only a relatively small minority knew about on their own in the early years to get to the East Coast, where, as was then generally known, the working conditions were on average somewhat better than on Malaka. About the working methods of the also Chinese coolie brokers themselves in the British ports on Malacca, but also about the treatment of coolies arrival in Deli, reached the British government in Singapore in 1870s. Serious complaints A ‘Protector of Chinese’ was then appointed in 1877, a European official who, with his assistant in Penang, was to supervise the recruitment.

In 1881, this Protector reported on his annual report, according to him, the working conditions of the Chinese coolies are up Sumatra’s east coast had to be considered inadequate and beyond cooperation of the UK authorities in the recruitment for these areas through Penang and Singapore therefore had to be reconsidered. The United Deli planters through J Th Cremer naturally responded with a fierce protest to the British government. They saw there in the report in the in the first place the hand of the competing cultural companies on the overhang. Shortly afterwards, the Protector had to take back many of his allegations, based if they were indeed found to be in part on information obtained from Chinese entrepreneurs on Malacca, who are also becoming increasingly short of labor and perceived the higher wages in Sumatra as a threat to their position. With that, the sting was out of the conflict for the time being, but the experience the Deli planters once more, and this time in an extremely painful way, the need for a more robust method of contracting agricultural workers.

The most obvious route was that of direct recruitment in the countries of origin As early as 1873, the Deli Maatschappij had made an attempt directly in china, which, however, had failed due to opposition from the local authorities. In 1888, a joint initiative of the five largest companies have the intended effect. Through the mediation of a German company, acting as agent for a newly established DPV Joint Immigrant Office, became immigrants to Sumatra in the South China port cities of Amoy, Swatow, Hoihow, Pakhoi and Hong Kong from that year recruited. In doing so, the members of the Association undertook not to contract coolies outside of the Immigrants Office; as a fixed fee. The planters paid the Bureau for recruiting and shipping the singkehs henceforth $ 60 per contractor. In principle, the agency should also take care of carry for return to China of contractors who have finished their term had, if they so wished. The practice of the following decades showed, whereas on average only one in six immigrants actually made use of this option; most settled as small traders, craftsmen or moneylenders in Medan and other up and coming plantation towns. The influx of coolies from southern China that came about in this way. Already in 1889 exceeded in number recruitment in Malacca, which incidentally also came under the supervision of the Immigrant Bureau of the DPV. By all kinds initial difficulties, direct contracting in 1888 with 1,152 immigrants was still modest, at least compared to the 2,820 in that years from Penang and Singapore. The following year, the ratio was already 5,167 to 3,494, and by the turn of the century recruitment to the overhang was practical discontinued. In 1902, 7,181 immigrants arrived in Belawan from southern China, against no more than three from Malacca. Over the entire period 1888-1902 A total of 70 111 contract coclies from China arrived in Deli and 17,827 out de Straits Settlements. Over 19,000 Chinese left during the same period from Sumatra’s East coast for remigration to their homeland.

MEDAN Beeld van een stad

M.A. LODERICHS E.A.

Leave a comment