Pictures of the tobacco culture in Sumatra

by Rudy Kousbroek

The development of the tobacco culture in Sumatra coincided with the heroic phase in the development of photography.

NRC Handelsblad, 16-10-1992

At an exhibition about tobacco in the Tropenmuseum you can see photographs of Sumatra of unparalleled beauty. They show immaculate emplacements, clean hospitals and clean coolie houses. The harsh reality remains hidden. By far, the most interesting part of the exhibition ‘500 years of tobacco culture’ in the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam is devoted to the development of the tobacco culture at Deli – that is the northern half of the residence East coast of Sumatra, around the capital Medan and the port city Belawan. This more or less separate part of the exhibition is so interesting is due to a curious coincidence: the period in which this region was developed coincided exactly with what could be called the heroic phase in the development of photography.

While the pioneers of tobacco culture were busy penetrating the primeval forest, building roads and rail connections, building bridges, planting and resting tobacco in their pre-galleries or celebrating hari besar in ‘the club’ . The first photographers also penetrated the area, armed with their plate cameras and tripods, capturing Deli’s dramatic transformation in photographs of unparalleled beauty. When looking at that exhibition, my emotion must also have something to do with the fact that I grew up on the east coast of Sumatra and that I recognize all kinds of things in those photos that I saw with my own eyes as a child. I did not exist in the period shown (1870-1930), but it clearly reaches into the world in which I grew up.

Most of the people in these photos had already disappeared from the scene, but large parts of the environment they had brought to life were still intact: many of the houses built at the time, the planting roads, the business yards, the ‘clubs’, the holiday bungalows in the mountains – while all kinds of traces of the style of life of that time had not yet been erased. And what of course, did not change were the mountains on the horizon, the rivers, the vegetation and the place names. After tobacco, Deli has experienced a second hurricane-like development, that of rubber; the course of events was analogous in many respects and it is thanks to this that I have experienced the tail end of all kinds of things: living in a wooden house on stilts at the edge of the bush, with monkeys in the trees and tiger tracks in the garden, club roads, floods; planters (my father) in white footwear, the burning down of primeval forest, gramophone music on the front porch; stopper bottles, leak stones, Berkefeld water filters and kerosene lamps, while in the rest of the world generations had grown up with electric light.

In the photos of this exhibition I saw things that I had not thought of in fifty years, such as the excavations in which a conical column of earth was left here and there, with a tuft of the original vegetation on top. I think to be able to determine the course of the soil profile. When I discovered that photo, I not only saw the color of the ground (brick red), but I also smelled the scent – a powerful reminder of memories, as we know, the scent of rains, fallen half a century ago.

The most evocative photos in the exhibition are not the panels with prints on paper, but the stereo photos on glass plates, which can be seen with the help of two antique stereoscopes of the ‘what the butler saw’ type, through the always gripping experience of depth. Ordinary photographs are images of the past, but what is kept in those mahogany cabinets is the past itself, chunks of it, forever hidden in the freezer of time, motionless and still; you look into it, transfixed: Medan, the Esplanade, the Kesawan, almost exactly as I have known it; bungalows in Brastagi, where I often played as a child.

There are also two photos of a car accident: an open car as there were still everywhere in the Indies in my youth, got off the road and ‘masuk parit’, spectacularly on its side in the ditch; which fact according to the caption, occurred on November 2, 1927. The car is immediately recognizable to an aficionado like me as a Packard Straight Eight; it belonged to Mr. H.J. Bool, a name known to everyone who knows his way around pre-war Medan, because of the street (Boolweg) named after him.

One of the photos shows that the old Bool made it there unharmed; he was the author of works on Chinese immigrants and the labor laws on the east coast of Sumatra at the turn of the century. Leaning over the side of his Packard, he stares into the lens. The late twenties!

The main tobacco companies have been in existence for fifty years (the Deli-Maatschappij sixty) and publish commemorative books. In the first harvest year, 1864, the yield was fifty packs, in 1871 there were 4,000; nearly a million guilders were converted in that year, eleven million in 1880 and almost 65 at the start of the First World War. which cannot be seen in a photo, but which cannot be avoided. Also in the exhibition, only the captions refer to what happened behind the scenes; the photos, the video shown on a video screen, show immaculate emplacements, clean cool houses, clean hospitals, and orderly tobacco plantations with industrious workers, a neat school for the coolies.

Yes, even a nice place to stay where older or incapacitated coolies who do not want to return to their native country can spend a quiet evening of life. And of course the great thing that was done: the primitive conditions in which roads and railways were built, bridges and houses built, and all the rest. The hard workers in white suits, pith helmets. The official image, as it was painted in the memorial books and in publications such as De Aarde van Deli by Willem Brandt.

The harsh reality described in obscure booklets and pamphlets, and unpublished documents such as the Rhemrev Report, was for years simply denied, ridiculed in the second room, and avoided in historiography as not spoken of in civilized society. And this polarization actually still exists. Jacob Vredenbrecht told ‘how his doctoral thesis on the Deli plantations, based on the reports of the Labor Inspectorate,’ caused consternation among the professor involved in Leiden.

He first said, “This was way too emotional because that couldn’t be true. No, this was impossible. ‘ I answered him, but the facts are these reports; that’s the reality. Another said that my thesis was not yet ‘ripe’. That was the Netherlands, in the early sixties!” The only modern Dutch work in which the Deli plantations’ reality is thoroughly and completely described is Breman’s Coolies, Planters and Colonial Politics, of which an extensive third edition was published this year.

In 1987, the same objections were heard again: ‘too emotional’, not ‘ripe’; the mature and non-emotional alternative is apparently to be silent. Incidentally, on closer inspection, something can be deduced about the actual relationships, as is also possible on the basis of the official literature of the time, which, out of necessity or unconscious naiveté, answers all kinds of questions that an honest and sensible person must ask himself.

For example, the description of runaway coolies as ‘deserters’, about which Van den Brand already remarked in 1902 that this word in the civil world can only apply to relations of slavery.

Deserters

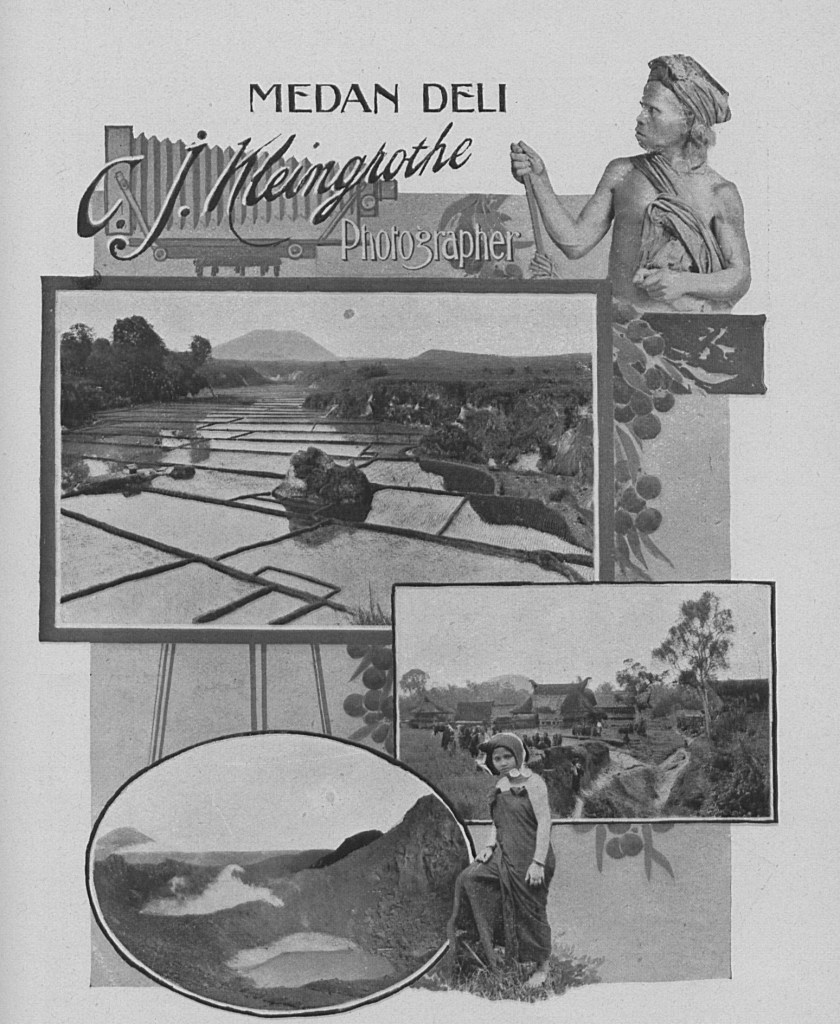

An impressive selection of old photographs from the same sources, including some that are also in the exhibition, have been used by Breman as illustrations in his book and are clearly gaining in significance in that context. Unfortunately, the captions are weak and sometimes, it is undeniable, somewhat biased. For example, a photo of three Bataks armed with spears and a Klewang in Breman’s book (p. 196) is subtitled not ‘Local tribals hunting deserters’. As with most recorded photos, the date, origin and name of the photographer is missing. This photo is by F Feilberg, who made a trip I through the unknown inlands of Sumatra in 1870, and depicts three Bataks in war outfit; the photo was thus taken at a time when the recruitment of ‘local tribals’ to hunt down ‘deserters’ could hardly have taken place. That such yachts were later organized is also correct. Some photos in Breman’s book come from De tobacco culture in Deli. This book contains a remarkable series of photos of the same piece of land changing from jungle to tobacco plantation (terrain cleared, drained, road built, bridged, drying shed and cool houses built, tobacco planted …). Others I have found in the Album der Amsterdam-Deli Compagnie (ca. 1900), with photos by Kleingrothe. C.J. Kleingrothe had a branch in Medan from 1901 to 1924 and many photos of tobacco plantations come from his studio.

The first European photographer to settle on Sumatra (1888) was G.R. Lambert, assisted by H. Stafheli, who later joined Kleingrothe; H. Ernst also worked with Kleingrothe. Other big names are C.B. Nieuwenhuis, who accompanied Van Heutsz’s campaign in Aceh in 1901 and later photographed many Deli plantations. J.W. Meyster, who had a studio in Medan from 1919 until the Japanese invasion, and G.A.R. Dittmann who worked in Asahan from 1901, of whom unfortunately, few photos have survived. This information can be found in Louis Zweers’ beautiful Sumatra.

Leave a comment