THE RHEMREV REPORT by Rudy Kousbroek

NRC Handelsblad

27-02-1987

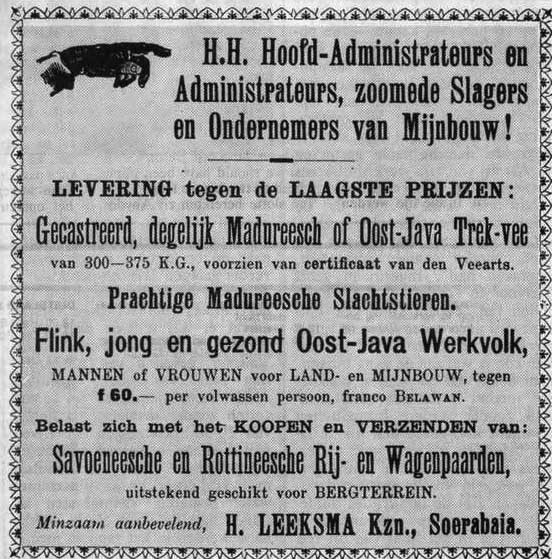

In 1903 J.T.L. Rhemrev, public prosecutor on Batavia, a report on the mistreatment and capture of coolies on the east coast of Sumatra. That report has been covered up. Jan Breman found it during a search in the General Archives. Next week his book ‘Coolies, Planters and Colonial Politics’ will be published, which includes the Rhemrev report in its entirety.

(His exotic name is Vermehr’s inversion: by colonial custom, illegitimate children were given their father’s name, but reversed.)

When I had not yet been in the men’s camp for a long time, a short, stocky man was appointed to me – that is Mr P, from company X: he used to drag the weeding women along by the hair curl if something did not suit him and sometimes he made them drink their own urine. And the one there, that was Mr Q, from company Y, who kept a kind of harem with which he created entire orgies on hari besar (rest day on the 1st and 15th of the month): ‘the oldest girl in that troop was sixteen’. Whenever I saw Mr Q bathing in the washing place, I always thought of that; I looked at his unimpressive organ (a cherry in a bush) and tried to imagine what his owner, a withered man with a pot-bellied stomach, had been up to. It was not the first time that I heard such stories: whispered details about abuse and sexual excesses on the plantations were already circulating at the Boarding School. There were classmates who had seen their father beat a native for themselves.

I had never known exactly what to believe, but in the men’s camp it became clear that such stories had to be truthful – everyone knew about them and they were spoken quite openly. I also got to know the context in which that always happened, that of: what do you want, they are rough bumps with a heart of gold, but where mincing is done, chips fall, you simply cannot bake an omelet without breaking eggs, with you will not get anywhere softness, it is the only language that the natives understand, etc. etc. You also instinctively felt that such things could not be discussed with outsiders, because they did not know the relations and would ‘judge it wrong’. It also followed from the way in which it was spoken that it was a lot harder ‘in the past’.

A book that you sometimes heard mentioned in this context was The Millions from Deli by a certain Van den Brand, a name that had not yet been forgotten on Sumatra’s east coast and was still capable of stirring emotions. It was only much later, when I started to delve into the relationships that had existed in the pre-war Dutch East Indies, that I saw the book for the first time. The following passage may give an idea of the content:… one day the inspector, who had taken the necessary precautions that his arrival” could not have been announced in advance, unexpectedly appeared at the company in question and at a “Kje, which had a barred window and a door, which was locked from the outside with a sturdy padlock. This cubicle was the hospital of the company. A Ruining stench lapped out of the lattice window and within it, in a space of several square meters, lay two Javanese, eight Javanese women and – a corpse. The latter, as it turned out, has been around since V | twenty-one hours. There was no opportunity to bathe, there was no drinking water, a facility to meet natural needs was not there. The latter was done on the ground and the sick scrambled with their hands some sand together in order to be able to cover their excrement with it and to slide it out through a butt under the wall. If the thirst became too unbearable for them, they would just have to trade in some drinking water from passing coolies for some of their rations of rice and dried fish … provided to them once a day. Once every fourteen days, the sick were given quinine.

These particulars of the ‘medical treatment’ were experienced by the controller, by questioning through the bars the unfortunate creatures that perished with dirt and vermin. who was obliged to visit the hospital at least once every fourteen days had not been worried about anything.

“… The sick, who certainly had not thought of ever coming out of this murder institution alive, were taken to the civil hospital in Lubuk Pakam, where one of the Javanese women also died within a short time. On her deathbed she was heard under oath by the controller and confirmed once more everything concerning the ‘treatment’ in the ‘hospital’ of the enterprise, in which she said more than forty days … She also announced that the tuan besar came every day to look through the lattice window and asked with interest to the sick whether she were not yet dead, while he z expressed my regret if this was not already the case … “‘Exaggerated’

When I first read these things I had few illusions; I had read books like Rubber and Coolie, by Székely-Lulofs and the stories I had heard in the camp suggested that what was described there was still under the truth. But nevertheless, I struggled with stories like this: I closed myself off from it. When I try to reconstruct how I did that, I end up with the same terms used by so many others: ‘greatly exaggerated’, ‘high exceptions’, ‘incidental derailments’. Moreover, it was ‘so long ago’. In fact, it was not: when the war started it was, to compare with now, about as close as the Drees cabinet is to us at the moment.

It was the time of the Aceh war, which was also fresh in the memory in 1942: there were several old-timers in the men’s camp who had still fought in it. So while I cannot say that I did not know about it, I have never been able to bring myself to quote from The Millions from Deli, not even in the polemics I have had over the years with various representatives of the ‘There something grand was done ‘mafia, who of course knew a lot more about the true facts than I did. But they kept their mouths; and I.

All things considered, that’s what Madeion Székely-Lulofs and others, even Du Perron, actually did. This may illustrate how easy it is to talk away the worst horrors, especially in your own circle: statements of the type just mentioned – exaggerated, sprouted from coolie fantasies and so on, high exceptions, individual derailments committed by foreigners – all these and such excuses, even if they are lies, become gratefully accepted, they are, as it were, anticipated and supplemented by the people themselves; not always from cunning or complicity, but simply to get rid of a nightmare. As a result of the publications of Van den Brand and others, the abuses on Sumatra’s East coast were regularly discussed in the Lower House as early as the beginning of the century, but ‘even the minister laughed when the speaker recounted the gruesome atrocities’, as F. Tichelman notes in a historical consideration of the SDAP and Indonesia.

Yet, as has now been indisputably established, that minister was fully aware of those ‘gruesome atrocities’. It was even worse than Van den Brand had described. Cover-up The facts, in short, are as follows: an official report on the conditions on Sumatra’s East coast, which was commissioned by the government and then covered up, has recently been traced back to Jan Breman, professor at Erasmus University. and the Institute of Social Studies; this report, accompanied by a monograph on The Labor Regime on Large Farms on Sumatra’s East Coast at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century by Breman, will now be published in a few days.

The document at issue here is known as the Rhemrev report, after the Public Prosecutor attached to the Council of the Indies on Batavia, JTL Rhemrev, who on 24 May 1903 was ordered by Governor-General W. Rooseboom to open an administrative inquiry. ‘set to’ the in Mr. J. van den Brand, entitled The Millions from Deli, alleged assaults and unlawful imprisonment of coolies and other persons working on industrial establishments in the said region, referring to the alleged irregularities in the judiciary of the magistrates. Rhemrev received additional instructions from the Attorney General to prosecute criminal offenses.

A month later he was in Medan and at the beginning of 1904 the report on his research was on the desk of the Governor General, who almost immediately forwarded it to the Netherlands. “During the discussion of the Indian budget in the Dutch parliament in the autumn of 1904,” Breman writes, “it was established that the minister wanted to keep the Rhemrev report out of the public at all costs. The formal arguments put forward by the minister advanced. For his refusal to even give the document for confidential inspection to MPs, those charged with crimes or other reprehensible acts had not been given the opportunity to defend the charges. Publication would also be of no further practical use. instead of dwelling on what had happened, he thought it better to focus all attention on the announced improvements “. This Minister of Colonies was the anti-revolutionary A. W. F. Idenburg, who from 1909-1916 would also be Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. After much insistence, he quoted some conclusions from the report: “nothing more than a tip of the iceberg,” said Breman, the political opposition finally accepted a motion tabled by government spokesmen. The minister was thanked for the information provided and he welcomed his commitment to take measures to put an end to the abuses identified in the coolie work in Deli.

Of course, to anticipate events for a moment, there was little. The labor inspectorate was set up, which was very small and could easily be fooled and the part of the coolie ordinance that gave rise to all the misery, the so-called poenal sanction, would only be ‘gradually’ abolished after 1929; not by order of the Government, but under pressure from an American threat to ban the import of Deli tobacco while it was still grown under de facto slavery, as this poenal sanction gave the planters the right to punish runaway coolies; a contract coolies were in fact completely under the control of the employer, which enabled him to force him to work for a derisoir wage. A legal minimum wage did not exist, and was not.

The Rhemrev report, Breman writes, “seems to have since fallen into obscurity. In one of the few recent publications on plantation society on Sumatra’s East coast (K. J. Pelzer: Planter and Peasant, 1978) Pelzer mentioned the assignment given to Rhemrev. The fact that he had succeeded in keeping his report out of the reach of researchers, this author deduced – rightly so as it now appears – that the data contained therein must be even more shocking than what Van den Brand put in writing. I came across this last statement when I was working on a study on colonial labor migration in South and Southeast Asia (J. C. Breman, Arbeidscirculation en rural transforwaf / in colonial Asia, 1985).

A search in the National Archives brought the Rhemrev report back to the surface. It had not been destroyed, as we would now fear, but only so well stored that it was kept confidential even after the coolie scandal had long since faded from public view. By including Rhemrev’s report in full, I hope that this source will still get the attention it deserves.

The Rhemrev report is excruciating reading. But it is not only the disturbing details that haunt you, which is especially impotent arouses anger is the image of the minister who cheerfully laughed in parliament the speakers who quoted Van den Brand and meanwhile knew very well that in reality it was even worse. It is this mentality that the murdered innocence portrays, that facade of clean decency which I have come to regard as the most miserable aspect of colonialism. “When discussing the Indian budget in 1900, Cremer (the then Colonial Secretary and as Delipionier fully aware of the situation) dismissively said that the annual Deli “Speech of this deputy bored him,” writes Breman, “(…) as mentioned, this minister again in 1900 denied the correctness of allegations of abuse. At a party congress, the socialist spokesman on colonial issues complained about the coolness and disdain he had in parliament … “

In every discussion of these topics, not only then but now, you get that same hypocrisy. Someone who had earned his spurs in that area was Willem Brandt, someone with whom I had a problem a few times and who, in my conviction, of the horrors that took place at Deli in the Dutch period must have been aware than anyone else, if only on the grounds that he had been the editor-in-chief of the Deli-Courant for many years before the war (that was the newspaper that in 1926 urged all nationalists to go against the wall without trial).

Someone who protested against this was Khalid Salim, which put him at fifteen years Above Digoel. The book that Salim wrote about this experience is already here from Furthermore, Willem Brandt was in the same men’s camps as I and it is therefore likely that the things I heard there also reached him; by the way, he had known all this for a long time. But above all: he published a history of Sumatra’s East coast in 1948, entitled The Earth of Deli, and it may be assumed that he also looked at some source material for this; it is almost impossible that he would not have stumbled upon the books of Van den Brand, Tschudnowsky and other publications on the coolie scandals. By the way, as I said, these names were known all over the East Coast: Willem Brandt knew them as well as anyone, of course. Nevertheless, he does not mention it in Deli Earth.

The whole book is an ode to what Du Perron already referred to as ‘the hard workers’ and written in – also a term from Du Perron – the ‘full crop sound’. It sounds like this: “… They have grown into a certain type, these East Coast men. They have made a land with their hands and with their brains and they feel connected to this land, firmly rooted in it; they love Deli more than any other country in the world, and it will always be the land of their homesickness. “Physically and mentally, the Delian is of broad stature. They are generally fellows like trees, with enormous shoulders and hands, a strong brown face, in which one finds eyes with the far-open gaze often found in sailors, and a powerful mouth, from which a thunderous laugh can be found. A boyish joy radiates from these enormous masculine figures. They are born optimists, and accept all of it evil and the good of the world with the same almost naive cheerfulness. Their sense of justice and fair play is particularly strong. They have a Malay word for it, which summarizes these terms untranslably well and that their coolies are dead on the mouth: patoet.

“For although in the pioneer years they sometimes treat the working people thoughtlessly roughly when they think they are not doing their duty, they are soft as butter when help is needed, and in the cold rooms they themselves play as midwives in a difficult case when there is no doctor is at hand … ” You would get tears in your eyes.

The Rhemrev report unfortunately gives a somewhat different picture of that for a midwife: “The assistant Moens has about two months to interview the contract woman. Atimah, wife of the native Bohin (the interrogation of the woman took place on July 29), because she had collected too few caterpillars, first inflicted a few rattan blows on her back and then kicked his foot in her loins with his shoe despite being highly pregnant (eight months). As a result of the kick inflicted on her, she felt severe pains in her side and in her abdomen. She became so unwell that she was unable to move. and. Her husband, who saw this, then took her in and carried her to the company in a slendang to the Javanese pondok. When she came home, her fruit shook violently. Four days later her fruit moved again and after that time Atinah felt no more life. Fifteen days after the abuse, she gave birth to a lifeless child. The child’s head was dented on the left side, so that the left eye could not be seen .. “

Funeral Soft as butter, those trees of guys with their wide open eyes. Especially when it comes to children. For example, a coolie named Tjitropawiro is described in the same way. kebon – the Mariëndal company of the Deli Maatschappij – sent to work by the administrator, Mr. Ingermann, with blows and punches after asking permission to bury his child, who died that night. When he comes home from work he finds out “Of his lawful wife Kernen, in particular, who, by order of her, the gardener of M. Ingermann had buried the body of his child without any solemnity”. Ingermann explains this “that the death of the child in question was no reason for Tjitropawiro to stay away from work.” Imagine, then you could keep going.

A detail that speaks volumes en passant is that an administrator could order the burial of a corpse without further formalities; if it is known that, as Van den Brand already noted, coolies were regularly beaten to death, the implications are clear. the heart beats that in the exceptional cases that a prosecution is instituted, the trial often cannot proceed because the witnesses have disappeared without a trace.

The Rhemrev report contains several examples of all these things. Overwhelming The sequence of horrors in the report is so overwhelming that it is not possible to give an impression of it in a nutshell. “About the same time, said administrator (JF Petersen), My keeper gave orders to the Chinese Ho A Tjit, Tjin Koean Kong and Fong A Sie, when they had to pass a river while carrying wood and asked for a drink, to tie their tails together and to keep them under water, which was burdened by his keeper was carried out by submerging the heads of these Chinese and, when they surfaced and spewed out the swallowed water, submerge them again “.

That the assistant D. Boys „..the Javanese women Tjemp and Sani .. after stripping her completely naked and with a leather belt on her bare buttocks, while they lay with their stomachs on the floor, several having dealt a fierce blows so that said body parts were covered with welts, and after his housekeeper had rubbed her face, breasts and shame parts with finely beaten lombok (Spanish pepper) on poles under the assistant house he then inhabited. feet, in such a way that each of the women came to stand between two poles with their legs wide and arms outstretched .. “

” ..when Kamiso one morning, about six months ago, on the road from the Saint Cyr Emplacement. To the top section of the enterprise near a barn under construction, Kamiso’s hands first attached to one of the reins or reins of his horse then climbed on horseback and then Kamiso, in that bound condition, dragged along next to his trotting horse, to the Javanese pondok about an hour away. “

The first pages of the report alone (the full report includes 82) provided these examples, skipping the ‘common’ cases of abuse such as being tied up, locked up without food, ‘djemoer’ (putting in the sun without drinking), administering 20-50 rot strokes, rubbing with djilatang or kemadu leaves (similar to nettles but much worse) and then watering them with water, trifles like blows with the fist or the flat of the hand are usually not even described separately in the report. Giving an impression of the entire report is simply impossible.

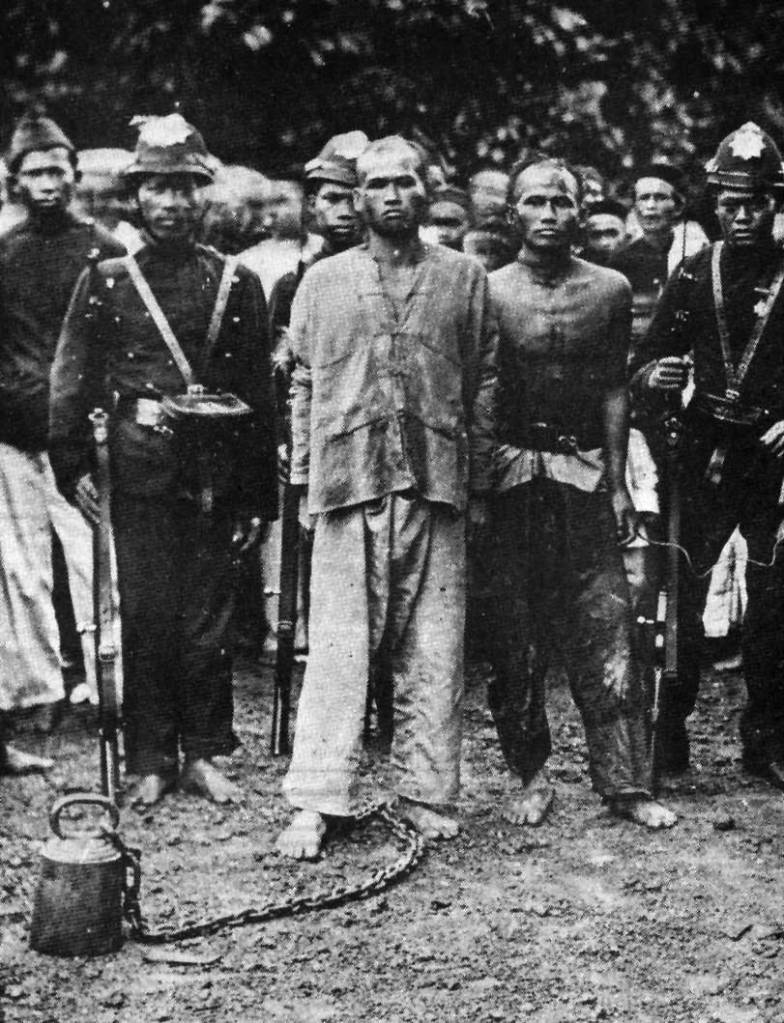

Add to that the fact that the investigation was obviously hampered and sabotaged by the planters, and as it progressed, more and more witnesses disappeared and traces were obliterated. The companies did not lack the means to pressure the coolies not to testify; multiple testimonies could be obtained only because some of the coolies were in prison and felt out of reach of their employers, or in the hospital, as in the case of the “2 Javanese contract women, (who) both naked, and a Javanese – in particular Gombong – whose shameful parts were only covered with a piece of kain but who was not wearing any clothes, were shown around the coolie sheds. was found and interrogated., also informed me. that one of the aforementioned women hanged herself out of shame and that the other in the afternoon, after being shown around, was beaten to death by the mandur Nur-Kasan – and then, at a coffee tree opposite the clerk’s house has been hanged.

“In other cases it is hatred and envy between the planters themselves that leads to the leaking of scandals:” Mention deserves what someone, who served as assistant on this company (Tandjong Kassau) under the orders of Mr. Van Beneden, informed me about beatings on coolies, attended by him. These assaults are as follows: the Javanese woman Prawiro arrived late for work one day. She had spent the night with the assistant Steyn Parvé. As a punishment, Mr. Van Beneden had her work in a ditch where she had to stand in water up to her stomach all day, apparently to give that woman a disease …

another Javanese woman, who had been punished by the Magistrate for desertion and brought back to the enterprise after the punishment had expired, was immediately after her return brought to the office of Mr. watered and defecated, and this while that woman was ill …

“Sexual mores Besides an illustration of what Willem Brandt called that ‘particularly great sense of justice and fair play’, so that the word ‘patoet’ their coolies’ on the mouth, “the above also clarifies something about the sexual mores of the undertakings, and the motives that could deter an abused coolie from bringing charges. Experience has taught, wrote Rhemrev,” that the coolies, al they also had the most legitimate cause for complaint, not easily accused their employers, only where the oppression was exceedingly great. expect to hear complaints “. The other chapter, the sexual mores on the enterprises, is a subject about which, of course, was never written, but about which the most fantastic stories circulated in the Delian world (and later in the men’s camp). In the Rhemrev report, the tip of the iceberg sometimes emerges: “… whereby this Head of Administration (the Assistant Resident of Asahan) informed me that the native Si Said, contract coolie of the company Oud Tanah Radja who had been sent for punishment , had informed him that his posting was related to an unauthorized relationship thing between one of the assistants of the enterprise and the wife of the aforementioned coolie. “

That ‘sending for punishment’, a custom about which Van den Brand also tells a lot about in The Millions from Deli, practically amounted to the planters they wanted to be able to have them imprisoned, by sending them to the Administrative Officer with a note stating what they had committed – often with the penalty already included, which would then be carried out without the slightest trial. Much more often the administration of the companies preferred to see a coolie continue to work and therefore prefer to give (corporal) punishment themselves, and because it was generally believed that the coolies were ‘too well off’ in prison They also preferred to be in prison themselves and sometimes begged to be allowed to stay. Breman says somewhere that more than twice as much was paid for eating a prisoner alone of what he received in wages on the plantations.

Incidentally, imprisonment also implied labor: the so-called squatters’ sentence (forced labor); In the dissertation of A. M. C. Bruinink-Darlang on the penitentiary system in the Dutch East Indies one can read how the Delian Cultural Societies constantly tried to exert pressure to increase the punishment for squatters. After all, the existence of the coolies on the companies was many times worse. That’s where the problem was: the monetary sanction turned the coolies into de facto forced laborers and enabled the companies to put them to work for such unbelievably low wages. Those wages were the source of all misery; it was also what forced the planters to such harshness: those who did not act in this way achieved no profit, and those who failed to do so flew irrevocably. At that level too, it was a ruthless society; the planters had high incomes and bonuses, but they lived under a constant fear of being passed over or fired.

Branches In my view, the Rhemrev report is the most gruesome revelation of this century for the Netherlands; what it brings to light is not only a history of suffering of such colossal proportions as to be beyond words, but also the extensive ramifications and complicities in the way the whole of the Dutch East Indies was ruled. The sober and business-like conclusions of Breman’s accompanying study on this are inevitable and terrible. An attempt will again be made to make this Delianian history an ‘exception’ and an ‘incidental derailment’, but it was not. The complicity of the courts in Batavia, of the Dutch East Indies government – for example, which had to be admonished by the League of Nations as late as 1936 to make serious progress with the ‘gradual’ settlement of the monetary sanction, of the responsible ministers in the Netherlands, of the ‘business’ and countless individual Dutch people is beyond any doubt. It is true that the Rhemrev report itself ushered in change and, to some extent, marked the end of an era. But only up to a point, as shown by the fact that this report was covered up in a very effective way. How it was possible to keep such a secret for so long would have to be thoroughly investigated. I also hope that someone will once again delve into the background of the assignment itself: Rhemrev was, as his name (a reversal as was more often used for the descendants of mixed relationships), an Indo. Was it a sign of courage and relief that such an assignment was awarded to an Indo, or was it, on the contrary, a conscious attempt to give the research as little chance as possible: who wants to know how those ‘men of the East coast’ with their wide open eyes , their boyish joy and their sense of justice and play about Indos should read J. Kleian’s anti-Indo book Deli planter.

I’m not sure Rhemrev wasn’t intentionally thrown to the wolves. State mines As Breman makes clear, it is also not true that such terrible things only happened on the Deli plantations. The situation at the State mines was also terrifying, such as at the Ombilin coal mines of Sawah Loento and in Redjang Soelit. “The mortality rate in this mine was as much as 37%. Horrifyingly (Hoetink) called the stories told to him how in the time of great death the corpses were regarded as dogs ‘seperti andjing’, the coolies said literally – were put under the ground or simply thrown into the river. At the beginning of 1902, Hoetink reported on his visits to several mines in the Eastern part of the Dutch East Indies. The Soemalata company had hired 851 contractors, of which less than half remained after a year and a half; 169 (20%) had died, 18 ran away and 132 had returned controlled, all this according to the statement of the management. The contractors were paid six cents a day, which even Hoetink found so outrageously low that he praised the coolies for accepting that. Those who worked less than 12 days a month – the sickness rates were very high – were not paid on payday but were tied to a stake and whipped. By the time the agreement expired, management was pressuring it to continue by refusing to resign; Reluctant workers were beaten and given no food until they yielded. ”Central Sumatra Road We commemorate the victims of the Burma and Pakanbaru Railway, and with good reason.

But who ever heard of the construction of the Middle Sumatra Road barely thirty years earlier? the aforementioned work by Bruinink Darlang can be read about what came to light about this in 1914. From an official report: “If the BB officials had properly fulfilled their duty and had regularly checked the health of the forced laborers and the conditions under the work and in the barracks, then they themselves would have discovered other abuses, namely the beating of the forced laborers by the laborers with rattan or bullhorn, the punishment of forced laborers by the laborers with self-conceived punishments, namely binding them with hands and feet a pole for four days and nights without shelter from the scorching sun and without eating or drinking and making it work Dosts brought up with iron chains on wrists or ankles ..

“A work boss named Kuiper” struck with his hand and dealt blows with the rattan cane and bullhorn, kicking and kicking not only the forced laborers who did not work as he wanted, but also the forced laborers who called in sick and said to them: ‘Here no one is sick, just ask pace (time) from Allah (God) and not from me’ He did not allow a sick forced laborer to be admitted to the infirmary until he could no longer stand and was already half dead; this was confirmed by the high mortality rate at the time .. “” Dr. Kievit stated … that he (had) examined many forced laborers who were at work with relatively high fever and dysentery .. “” The controller BB stated. … that the transport of the sick forced laborers was very bad; they sometimes died on the way, even the seriously ill had to walk great distances. “

We have been complaining about the Japanese for forty years, but how do such abuses actually differ from the actions of the Japanese? The death and beatings of the Burma- and Pakanbarus Railway we have sorted out to the smallest details, published lists of names and memorial books, but about all these Indonesians killed and perished by ourselves and their names have been forgotten forever. paradise at the equator, but I find this shameful and disgraceful. What always makes me so enraged is that it is especially the people who know all these things very well who rave the hardest about how we were treated, like Willem Brandt, the one about the camp in which both he and I lived, and which cannot be compared with the horror described here kings, has told the most fantastic lies for years. Damn, from now on at the August 15 commemorations, let’s talk a little bit less about ourselves, and a little bit more about those untold and nameless wretches we worked to death, starved and kicked to death.

Leave a comment