There are three groups of people in Indies according to the division of the law: Europeans, Natives, Foreign Easterners. That has not always been the case. The old Government regulations knew only Europeans and Natives and for each group “those who were assimilated to them”. For the Europeans, these were the Japanese (since the beginning of this century) and the other “persons from elsewhere, who would be subject to a family law in their country, essentially based on the same principles as the Dutch”. And with the Natives were equated: “Arabs, Moors, Chinese, and all not mentioned in the previous phrase, who are Mohammedans or Gentiles.”

This distinction was mainly made with a view to the administration of justice, taxation and education. It should be borne in mind here that the aforementioned division of the population entirely intersects with the division that can be observed in every society: the stratification according to prosperity and development. The wealthy and the more educated among the Chinese felt the expression “equated with Natives” as demeaning. Not only that they had to stand trial before the Land Council, ‘the daily rights for the Native’ and there also had to see their civil disputes brought to justice, but above all, that in the case of minor offenses they had to go before the police judge in the midst of the criminals from the kampong. had to appear, they considered insulting to their appearance.

In 1907 the division into three groups appeared in law, and the third group is officially called that of the Strange Easterners. The description of who belong to them is quite negative, because after determining who are Europeans and who are Natives, become third group left all who do not fall within the terms of the first two groups.

It is interesting to note that in the later years a tendency has arisen among the Chinese against being placed in a separate group. But now the aim is to be equated with the Europeans, or rather, to be subject to the same law that applies to Europeans. And in that direction the development is also going through the unification of law, of taxes, but mainly because the Chinese themselves change. The younger generation is abandoning many of the old customs and thus approaching European views. Whether this will be entirely for their benefit, especially the relaxation of the patriarchal family life, on which all Chinese society rests, I venture to doubt.

Thus, the Strange Orientals are the ones formerly described as: Arabs, Moors, and Chinese. The Arabs, who by their faith are so close to the Natives, will not be spoken of in this book, because to them and; their influence will be dedicated a separate particle in this series. Moors is the old name for Pre-Indians; There is a lot to be said about them here. But there is more to be said about the main group, both in number and in economic importance: the Chinese.

Various tribes are represented among the Chinese in India. Most important are the Hokkians, also often called Amoy-Ohinezen, after the port of the province where they sailed. According to the 1930 census, there were almost 555 thousand or almost 47% of all Chinese in the Indies. They are mainly established as traders and that also explains why 65% of the Chinese are Hokkian in Java and less than 29% in the Outlying areas.

In numerical strength, the Hakkas follow with more than 200 thousand (in Java 18%, in the Outlying areas 21%). These Hakkas invaded Kwantung province from the North in centuries past and are therefore also called Keh, that is: guest, stranger. In the Indies they work a lot in small businesses, such as shoemaker, rattan weaver, tinsmith.

Then the Kwongfoe’s come with more than 136 thousand (Java 7%, Buitengewesten 16%). These are the actual Cantons, but because they used to ship a lot in the Portuguese port of Macao, which allowed them to avoid the emigration barriers, they are still referred to as Macao Chinese. In the Indies they work a lot in the finer small businesses: goldsmiths, tailors, traders in clothing supplies, furniture makers.

Finally, as a separate group, the Tio-chués can be mentioned with 88 thousand (in Java 1%, in the Outlying regions almost 14%). These percentages do show immediately what their main work is: coolie on the culture enterprises. They come from the region, which is aimed at the harbor town of Swatow and are therefore often called Swatow Chinese.

Many other tribes are represented in our Indies; the Census gives for this, together with those of unknown origin, around 200 thousand or 17% of the total. The peculiar thing is that of some tribes only people living in India who exercise a certain profession, such as the Hailams from the island of Hailam or Hainan, who are house and hotel servants.

This, of course, is not caused by the fact that these Hailams would not engage in other professions in their own country, any more than the other tribes, of which I mentioned profession or business as an example above. The cause lies simply in the fact that someone who succeeded in the Indies stirs up others in his former environment to also emigrate. For Deli, people were even familiar with the so-called laukèh recruitment: the old guests, who repatriate and receive a bonus for their newly recruited coolies. It is also obvious that the owner of a business only hires fellow countrymen, if only for the sole reason that he does not understand the language of the other tribes.

Yet as a European one notices very little of the difference in the origins of the Chinese. Only when the company name, the so-called ‘brand’, indicates this origin. They like to use a spell, of which the first word sounds just like the first word of the name of the country of birth. In Medan, for example, there are many furniture makers Cantonnezen and there was a street, where there were six furniture makers’ shops next to each other and all their brands started with Kong or Kwong: Kong Wo Loeng, Kong Soen Ho, etc.

Much more than the difference in tribe, us Europeans are interested in the difference between the hikers and the stayers. The hikers are the newcomers, born in China and who came to our East as adults. They are sinkèh, literally new guests, orang baroe. They have all the qualities of a bier, especially expressed in a wonderful hassle with language. However crafty they are as merchants, however handy as a workman, their wonderful language often makes them seem clumsy. The klontong, who passes the houses with a few large packs of silk fabrics and lace, and praises his wares as “lèn-da lèn-da mu-la; soe-te-la ba-boe-laa ”(rendarenda mokah; soetera bagoes = cheap lace, beautiful silk) one of those looks like stupid, but it is far from being.

And on the other hand, the stayer, usually referred to as peranakan. Actually, this last word should be: peranakan tjina, referring more to children of Chinese fathers and Native mothers. In the old days, when emigration from China was forbidden, almost no Chinese women came abroad. A Chinese, who could afford it, married a Native woman and his children became Chinese. That is entirely in accordance with their family law. Even if the man in China would already have a wife and children, the children of the native concubine have the same rights as those other children. To Chinese adat, kinship exists only along the male line; the possession of male offspring, even if they were conceived by congregation and even in women of foreign race, is of the utmost importance. There is still more to say about this in the so-called ancestor worship. In any case, this conviction made that the descendants of immigrant Chinese also remained Chinese themselves and did not follow their mother and thus merged into the Native population.

It is difficult to say with certainty which part of the Chinese population in our Indies is blood mixed. The 1930 Census has not been able to ask this question directly, but it has put forward another question, which gives some idea. This is because the questionnaire not only had to be filled in as to whether the included resident was born in or outside the Indies, but also whether or not his father was born in the Indies. In this way one has a fairly good impression of the number of Chinese who already live in the second sex in our East.

In densely populated Java with its 42 million inhabitants, remember: that is 316 per square kilometer, so it is the most densely populated country in the world, where the group of Chinese of 583 thousand souls is only 1.4%. Two thirds of them had a father born in the Dutch East Indies, so can be counted as real stayers. Only one fifth of all were born outside the Indies.

In the Buitengewesten the relationship is very different. There the total number of inhabitants is 19 million, that is to say 11 per square kilometer. Of these, 650 thousand are Chinese, so even more than in Java. Although that is only 3.4% of the population, it is still relatively two and a half times as much as in Java. The distribution across the different islands is striking. There are regions where the Chinese element constitutes up to 17% of the population, such as Bangka and Billiton, Riouw, West Borneo, a part of the East coast of Sumatra, all areas in a large circle around Singapore. In the Outlying regions, only one quarter of all Chinese are already second-sex in the Indies, compared to two thirds in Java, as was said before.

Yet another Census figure gives a good picture of blood mixing. In the classification according to the tribes, nearly 11 thousand of the Chinese have been counted, who are ‘of indigenous country’, mainly women, married to Chinese. Half of them are Javanese. The blood mixing among the stayers of the Chinese is therefore undoubtedly very great, so great that people tend to regard them as a new race, the Indo-Chinese. That name is sometimes used when referring to the legal opinions developed in this group, but he is not very happy. After all, people think of the inhabitants of the French Indo-China and that creates confusion. In daily life baba is often said to these Indian Chinese, often in contrast to sinkèh for the newcomers. The meaning of that word baba is unknown, but those involved are usually not very fond of it, as well as the claim tjek, which is used in the barracks. Yet this last word is originally of good meaning, namely uncle, and it would have been adopted as such for the claim of well-to-do Malays: entjik.

By the way, that sensitivity to words, which fully acquired civil rights, is more common. When speaking of China and the Chinese in Malay, the words negeri tjina and orang tjina are used. However, the young people in particular now feel something derogatory in that word tjina; they prefer that it be said in its place: Tiong-hoa, according to the Hokkian pronunciation for the Middle Kingdom.

This brings me to a dividing line that can be drawn between the Chinese in India in another sense, more or less in a political sense. We have seen that in centuries past the Chinese emperors threatened the emigrants with death upon their return; they have not cared about their fellow countrymen living abroad. That has changed somewhat, when at the end of the last century it turned out that the coolies recruited in China were doing very badly in some countries. But it was only under the Republic that interest in the foreign Chinese became so great that they are even considered Chinese subjects. At this time, the domestic politics of China is followed with interest, especially by the young people, and the people’s party, the Kuomintang, for example, also has important supporters among the Chinese in India.

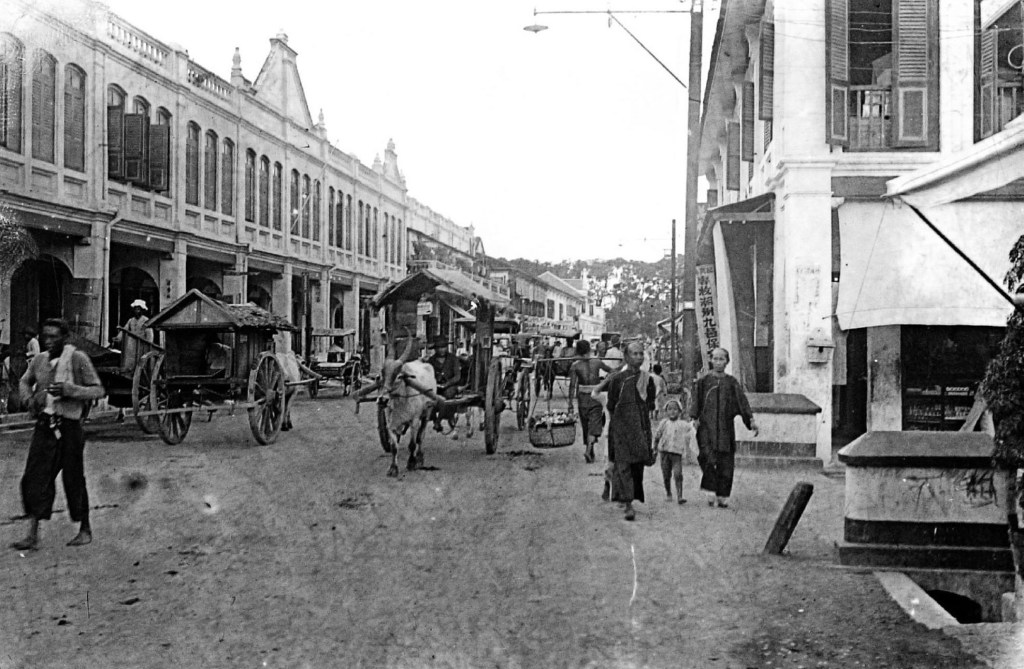

This political revival has mainly contributed to the repeal of various provisions placing the Chinese in an exceptional position. For example, the requirement that a Chinese had to apply for a Special pass to move outside his residence, which regulation was withdrawn in 1914 for Java and in 1918 for the Outlying regions. Likewise, the prohibition of living outside a designated neighborhood, the Chinese Kamp or kampung tjina revoked in 1919 for Java, in 1926 for the Outer Regions. Both schemes had long since been allowed by the many exceptions for the better and more developed to lose their sharp sides, but they still felt like unfair obstacles. The stratification of the Chinese convergence runs right through the various dividing lines mentioned here.

Extreme cases are found in both respects. Among them are millionaires, landowners, businesses, factories, and humble artisans among them, who earn little enough to keep soul and body together. There are academics (by the way: no less than 40,000 Chinese can write Dutch) and there are workers, whose interest does not go beyond the bite to eat they have to earn.

The clan names also have a meaning; often it is a very common word, which should not be translated either. Most clans have histories, of course, which can show the origin of the name in very ancient times. I have already said that persons of the same group regard each other as blood relatives, and that often in a case only servants are hired who are related to the owner in this way. There is often also a patriarchal relationship in a case. The owner or the main kongsi member in Java is usually named after Dutch boss, on Sumatra usually Taukeh not only employs the servants for wages, but also provides them with room and board. For example, they can often be seen eating at the back of the shop, gathered around a large round table. A bowl of steaming white rice in the middle and around it some saucers with added food. Each person fills his own rice bowl, which he holds in his left hand; With the two chopsticks in the right hand, some of the food is taken from a bowl and placed on the rice and then the bowl is brought close to the mouth to be able to eat a good bite. The handling of those chopsticks is not difficult at all, but the dexterity must be equally good to move both sticks in one hand like a kind of tweezers.

A Chinese generally likes good food and therefore their cooking has been able to enjoy the preparation of very complicated dishes. Yet the Chinese can also be extremely sober. They have usually a strong sense of saving, which means that they can easily resist the temptation. They are also sober in their stimulants. Tea, which is ready all day long, should not be regarded as a stimulant; it is drunk very weak, without sugar or milk. Drinking tea, even if it is only a single leaf on a kettle of water, has a great hygienic significance. After all, because of this they drink the water always boiled and that is, in the very polluted environment, such as one finds in the cities in China, much better than drinking well water. A general friendly custom is to put a large kettle of tea with a few bowls at the front door for the convenience of passers-by.

They are also moderate in the use of tobacco. Their tobacco pipes do not have a large head, which is stuffed full, but tobacco is turned into a pill, lit with a wick, and then the ~ Took is sucked in by water. Ordinary workers have often made a pipe from half a meter long piece of thick bamboo, closed at the top and bottom, in which at the bottom a side pipe for the tobacco wig and a side pipe at the top as a mouthpiece. When the tobacco has been smoked in a few strokes, the wad of ash is removed by blowing briefly. Wealthy people, insofar as the cigarette did not supersede this practice, use a finer and smaller metal pipe, often decorated with cloisonné. These pipes are mistakenly mistaken for opium pipes by Europeans.

Opium pipes are very different. These are straight pipes, about thirty centimeters long, with a thick head of metal or porcelain in it, in which a small hollow. There, the pea-sized ball of the heul juice is put in, after it has been heated over a flame and then the smoke can be inhaled through the pipe. This smoke is sufficient to give the user a pleasant intoxication. It is not entirely certain whether the physical damage from moderate opium use is as great as is generally believed. But the moral damage is very great, for the awakening from the intoxication appears to be extremely unpleasant and makes a new pipe with double the force provoked. Anyone who lets opium slide into the habit has come down a slippery slope. The dose to attain the pleasures of oblivion, must be taken ever larger and an ‘excessive use’ without a doubt destroys the body. Before it gets that far, however, moral resistance has long been broken. Those who shift a lot no longer have time to work or to look after their affairs; opium is expensive and thus a slider will easily go down the path of crime to obtain it. It becomes a vicious circle, because the greater the worries, the greater the desire for flight in the dreams.

Usually opium sliders are mistaken for a specifically Chinese vice. That is not correct. In any case, the custom is not of Chinese origin, but was brought to China by Arabs towards the end of the sixteenth century. So that is actually in recent times for a people whose history dates back to a few dozen centuries before our era. In 1729, the first imperial edict against the use of opium was issued. The entire opium import was then in the hands of the Portuguese, who bought it from Goa (on the Western coast of the East Indies) to Macao. The edict was repeated several times, but it was not until 1800 that all imports were prohibited. For 40 years, this ban has provided a generous source of income for the mandarins, because more money can be made from illegal traffic than from open traffic. Then by imperial order, the import ban was strictly enforced and the opium stock, also from foreign traders, seized and destroyed. That this had to lead to the so-called Opium War is doubly embarrassing for the West. Not only were the Chinese in their right to trace the contraband, but they also had ample reason to reproach the Europeans for seeking their profit in a commodity that so undermines popular power.

In the Dutch East Indies, the opium use was probably mainly introduced by the Chinese, but it was by no means limited to this population group. The reports of the opium director give figures on this; for example, in 1930 there were more Indigenous than Chinese opium sliders, 86 thousand against 80 thousand. Relatively speaking, this is of course much higher for the Chinese, because it means that it is almost 7% of their total number. And they use three quarters of the entire official opium flow! The distribution by regions shows that it is more the sinkehs that slide, because the east coast of Sumatra and the regions around Singapore have by far the largest number of opium customers among their Chinese inhabitants.

The legal manufacture and sale of opium is entirely in the hands of the Government. The factory, where raw opium from Bengal is processed, stands as a dismal symbol in Batavia between the hospital and the pawnshop. Delivery is made in a large number of official sales points only to holders of a license.

The opium control system that has existed since 1893, which has gradually been expanded throughout the Archipelago (with the exception of the prohibited circles), undoubtedly helps to prevent the worst abuses. Previously, the retail sale of opium was leased per region, and this system means that the lessee has an interest in the greatest possible use. It is a pity, however, that the Government derives a very important benefit from a vice, even if that benefit only constitutes a few percent of the budget.

In any case, much is already being done for nursing, especially opiophage withdrawal, and an attempt is made to keep the growing generation away from them through education and literature. It is to be hoped that the government should also interfere with alcohol, because cognac and arrack are often used as medicines. The Indigenous world is also getting used to this and it is better that the Native, who has less thrift than the Chinese, is kept away from customs that undermine the sense of responsibility. What now well-to-do afford is gladly imitated by the simple man.

At first sight, it is difficult to judge whether the Chinese are dealing with a man in bonis. The youngsters, insofar as they do office work, dress as European, but the old-school man also likes to stick to the old costume. I do not mean the traditional costume, which is still commonly seen in China, made of silk, in the colder days with a quilted silk overcoat. In the Indies, the clothing must first of all be airy, which is why the Chinese wears cotton trousers of unlikely width with a very low crotch. The band is folded around the waist in a few folds and then rolled over, which keeps him seated. Only Chinese wear such pants; with most of the other orientals men wear, like women, a kind of skirt, a leg-garment, either sewn up into a tube, a sarung, or a straight piece of cloth, put on in more or less pleats.

The upper body is covered with a net shirt or with a jacket, a kabaya of thin cotton, without a collar and buttoned at the front. The black shiny Chinese fabric is rarely seen wearing. So the bass often sits in his shop in a negligee, which is not at all in accordance with the importance of his business.

There is a much greater variation in women’s clothing. One can still see older females with ‘golden lily feet’, the feet mutilated at a young age, on which they can only stumble. They were certainly not born in the Indies and they often adhere to the gloomy Chinese costume of black wide pants and long kabaja. Foot binding has also been much less common in China since the Revolution, but the unfortunate victims of this cruel cosmetic are less likely to get rid of it than the men of their tails.

The other women, especially those from families who have lived in the Indies for a long time, wear a costume that is attuned to the Indigenous costume, as in earlier years worn by European women: sarung and kabaya. For sarung they use tie-dyed fabric, but not in the covered Royal colors blue and brown with a fine dotted pattern, but rather the patterns that are produced along the North coast of Java and which are often inspired by European patterns of the beginning of this century. So in general more substantial in design, with a light background and bright colors green, red, yellow. A white kabaya is also worn. Indigenous women never wear white kabaya.

Young girls dress differently. They often wear dresses like European girls, but they also like to return to old Chinese dress. A kind of beach pajama made of colorful stol: wide trousers and a short kabaja with a standing collar, the side closure in the color with which the whole thing is bound. It looks bright and seems very practical in the tropics.

How does the Chinese now earn his money in our Indies? The table below, for which the figures are taken from the 1930 Census, gives a good picture of this. It concerns the numbers of Chinese workers, grouped by profession or company, in which they work. In the first place, it is striking that the vast majority (more than 57%) in Java are active in trade. The Chinese do indeed fulfill their most important function in Indian society: the middleman. Then, but only more than one third of the previous group, those who find their existence in industry, mainly the small companies: makers, furniture makers, tailors, tin makers. In Sumatra, this group is even higher in number than the traders. The Malay is probably a better competitor in the retail trade than the Javanese, but few Natives enter the small business.

More than four thousand workers work in the mining industry (which, incidentally, is few in Java) and in companies. So these are almost all coolies and on Sumatra their numbers are not less than that of the workers in trade and industry combined. There is another important group working in so-called indigenous agriculture and horticulture. That does not mean that they are employed by Natives, but that they practice agriculture and horticulture as a small business. Almost the entire vegetable farm on the east coast of Sumatra, with an important export to Penang and Singapore, is in the hands of Chinese.

NUMBER OF CHINESE WORKERS

Java Sumatra Other Archipel Inl. agriculture and horticulture 11,104 30,056 9,280 Enterprises. . 3,809 31,730 85 Mining. . . . 585 42,101 2,910 Industry. . . . 38,068 43,645 12,280 Traffic 5,178 6,313 1,263 Trade 105,445 42,104 24,430 Other professions. . 18,700 35,210 5,644 182,884 231,159 55,892

It is therefore mainly in trade that the Chinese find their existence in our East and as such they form the indispensable link between the importers and exporters on the one hand and the mass of the millions on the other side. The Chinese are the retailers, who sell everything, and the buyers of everything that is produced in Indigenous society and has significance in the world market. Wherever there is a chance of profit, you will find the Chinese, even in the most wonderful forms of commerce and in the remotest corners of the country. Of course they have also managed to conquer their place in the wholesale trade, but the main thing remains the intermediate trade, and that also for the Europeans. There are European shops in the larger towns, but not all of their compatriots have them as customers; they are often a bit more expensive and less lenient than the Chinese. Because in the Dutch East Indies people pay much more attention to the brand when it comes to imported goods than in Holland, there is no need for a difference in quality between what one delivers and what the other delivers. So if the Chinese is a bit cheaper and gives credit a bit more easily, he will attract the customers. When, in a time of malaise, things go awry, because customers no longer pay, then it often becomes apparent during bankruptcy that the Chinese’s leniency is based. He works with very little capital and for the rest he relies on the credit that the European importers grant him. In the event of bankruptcy, it has sometimes happened that twenty times the entire trading capital of, often dubious, outstanding claims appeared among the assets. When the importers grant him credit for several months, the shrewd merchant tries to get rid of everything within that period with a small profit if necessary, and he pays with what he himself received, without having to count on a cent of his own interest on capital.

The trade morality of the Chinese in general is often disdained, and indeed his thirst for profit leads him to the excesses of usury and illicit trade. They usually combine their usury with some kind of trade, so don’t just lend money at heavy interest. The latter also occurs, of course, and it is understandable that a large percentage must be calculated for the large risk and the collection of many small payments. That would not be so bad and it can be safely said that the Native must then become wise through damage and shame. But their interest calculation is not that simple, because they immediately factor in the expected profit. They do that with regular sales as well. When they buy something for one guilder and hope to lose it for one fifty, they speak of roegi, loss, when one forty is offered. Similarly with a loan. When someone borrows $ 100 to pay in ten monthly installments, and if, for example, 2% interest per month is expected, it is stipulated that he must pay NLG 12 a month. The percentage is actually much higher, but that is not so bad. The worst only begins when the debtor can no longer pay. Suppose he has paid off seven times, so in all, NLG 84.-, then it is reckoned that he still has to pay NLG 36.-. Now the Javanese is quickly inclined to value future earnings, but that is often disappointing. If he’s not only struggling to pay off now, but even needs some more cash, then comes the novation. He receives some new money, to which the NLG 36. is added (which therefore contains undisclosed interest) and the monthly percentage is again calculated over the whole.

In addition, as I said, most of the usury is tied to some sort of purchase transaction. Mainly to advance the harvest, but also a lot the delivery of goods on installment. This is often a matter of a few cents a day from women, who bought a piece of cloth for a bath. So one sees the creditor pulling the kampong through, with his bundle of merchandise, with his pajung, notebook and abacus, in order to receive a few cents here and there in ‘deduction’ from the purchase price. That word has penetrated into the Native languages, and so the Tjina mèndrèng is not a pleasant sight in the kampung. Fortunately, that the popular credit system is able to prevent the worst excesses.

Much of what I said before shows that the Chinese act little as an individual, but more in union with others. He is part of a family, he trades in kongsi, he is really someone for social life. There are therefore an incredible number of Chinese associations. One of them I mentioned in passing, the Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan. In contrast to the many associations of members of the clan or of people from the same district, this is a general association for all Chinese. The first two words, Tiong Hoa, stand for China as a whole, and it is important to see that when it was founded in 1900, so far before the revolution, which is attempting to forge China into a nation, this national awareness already manifested itself. came. But the basis was still very conservative, because the statutes describe the purpose as:

These precepts put the importance of education first, as I have already said, and it is therefore obvious that the association should focus in the field of education.

was going to fail. Already in the first year after its foundation a school was founded in Batavia, which over the years was followed by many throughout the Indies. This part of the task of the Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan is so important that one actually overlooks the other work and considers the association exclusively as a school association. Indeed, more general associations have also been established, especially among the young, which have taken over much of the original social and cultural work of the parent association. And above all, they are more modern oriented. The Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan harks back to ancient China, to Confucius and his teachings. To make this accessible to all, even parts of his work were translated into Malay. The schools were therefore also arranged according to the Chinese model, where the old language was albeit according to the so-called Mandarin pronunciation. But the new Chinese ideas were also imported with the teachers and the school books bear the stamp of this. The awakening of the East is reflected in this, and so hypermodern spiritual food is served up to the younger generation in age-old dishes. This is undoubtedly largely the reason that the Chinese in India have started to focus more politically on China.

There is another cause for this. As much as one may desire an education in the classical spirit for the youth, practical life also required the knowledge of modern languages. De Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan wanted to link a course in Dutch to her school, because the knowledge of this language would be of immediate use. But the Government did not cooperate and even refused permission for a lottery to provide the funds for a Dutch teacher. Subsequently, English was learned as a modern language, because the Chinese teacher need not be so expensive for this. Not only that this made a difference for the children of primary school age, but especially for those who wanted to continue learning. They went to Singapore or to China, because there were no further possibilities for them in the Dutch East Indies.

Fortunately, the government’s negative attitude did not last too long. In 1908, after long deliberation, a start was made on Dutch-Chinese education. As in the Dutch-Native schools, these Dutch-Chinese schools are taught in Dutch and the curriculum is virtually identical to that of the European primary schools. In any case, these schools also provide access to further education, and the Chinese have indeed made use of it. The Indian Colleges have many Chinese students.

The Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan also participated in this multiple appreciation for the Dutch language. The opportunity for this was opened by the Hollands-Chinese Kweekschool in Meester-Cornelis, which was founded ten years after the first Dutch-Chinese school. Br are now Chinese teachers with Dutch qualifications and so this language could also be taught in addition to or as a replacement for English. Insofar as the students do not continue studying, they can be satisfied with their knowledge of classical Chinese to satisfy their national feeling and of Dutch for practical life. But those who want to study further miss the connection. It is simply not possible to expand the already full program of primary school with a subject as difficult as the Chinese language. Hence now the criticism of the schools of the Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan, that would have been set up too idealistically. Perhaps that is the case and indeed modern education is very much at odds foreground the gathering of knowledge and forget to some extent that upbringing should above all also aim to build character.

The trade unions are more focused on practical results. The practitioners of the same trade or traders in the same article join together: the goldsmiths, the tailors, the hardware traders. In such trade unions are not only the self-employed bosses, but also the workers and servants. It is also not only the professional interests that are advocated, but, as with any Chinese association, mutual assistance is pursued in many forms. They are continuations of the guilds that have existed in China since ancient times and had great influence there. It is always a peculiarity of the Chinese that they do not see colleagues as competitors. That is why practitioners of the same profession very often live next to each other. In Chinese cities, entire neighborhoods are devoted to a certain subject, and in India this is also the case in small parts. For example, Medan had a goldsmiths street, one where pottery was sold, and another where an entire line of harness makers were located. The view then is that everyone must ensure a living by the quality of his work and by his price. This will undoubtedly benefit the profession, to which the power of the guild board also contributes, which not only can resolve disputes between the members by mutual agreement, but also has a certain criminal jurisdiction. that each must ensure a living by the quality of his work and by his price. Undoubtedly this benefits the profession, to which the power of the guild board also contributes, which can not only resolve disputes between the members by mutual agreement, but also has a certain criminal jurisdiction. that each must ensure a living by the quality of his work and by his price. This will undoubtedly benefit the profession, to which the power of the guild board also contributes, which not only can resolve disputes between the members by mutual agreement, but also has a certain criminal jurisdiction.

Mutual assistance is not limited to financial assistance. A peculiarity is, for example, that at a funeral in the family of a guild brother the others join the procession and there is even a fine fond of neglecting this duty. Still different are the trade associations Siang Hwe or Siang Boe, also referred to as the Chinese Chamber of Commerce. These do not limit their activities to commercial matters. They were established in various places in the early part of this century under the influence of China; in 1935 these local associations merged into a general Chinese trade association. The power of these associations is often not unimportant. As a representative of the brokerage as a whole, they could, for example, negotiate conditions from importers that an individual customer could never obtain. They have sometimes gone so far as to be able to obtain “voluntary contributions” by threatening exclusion for beneficent purposes, such as establishing a Chinese school. Even it is not unlikely that funds were obtained in this way for political ends. Incidentally, the weapon of exclusion or boycott has been used entirely on political grounds against articles of certain origin and then with threats and even acts of violence against traders, who still continued to sell these articles.

The “secret societies” go one step further. These, of course, flourish among the Chinese, who are so eager to join together, who love mysticism and for whom the elaborate decorum of the old days is still respected. There are secret societies of a purely religious nature whose purpose is to promote a clean course of life for the brethren, but there are also many whose purpose is political. And also societies, which at the core of the mystery sensible fuss to pursue a certain goal and this is also what people in our Indies have to do. These are then confederations for mutual aid to the utmost, so that, for example, the oath brothers never bring mutual disputes before the government judge, but let the board decide. And in case an oath brother himself has to deal with a judge, in a civil case or in a criminal case, he can count on his colleagues to always testify before him. Such a society then forms a state in the state and if, for example, the smuggling of opium is one of the purposes, it is very difficult for the government to track down.

Another peculiarity is that these secret societies in

Borneo also joined Malays and Dayaks, who swore the same broad oath and submitted to the jurisdiction of the government. That this was not a mere formality, can be seen from the fact that these societies impose corporal punishment and even death on some offenses, and because only oaths are involved in their execution, no complaints about assault or murder are therefore brought to court. It is clear that the power of a somewhat expanded society is great and leads to the terrorization of others, who do not dare to complain for fear of worse. The secret societies are therefore a veritable cancer in Chinese society in some areas.

VREEMDE OOSTERLINGEN door Gerard Jansen

Leave a comment