The modest hotel at which I had established my residence was situated on Paleisweg out near the southern end of town in one of Medan’s oldest European quarters. It was a district of enormous bungalows set in spacious grounds behind tall bamboo hedges. Many of the properties were badly overgrown with tropical gardens which had got out of hand and run riot. The framework of the houses, although still solid, was bronzed with age. Near-by, these homes presented a somewhat dilapidated appearance but, from a distance, they still continued to reflect the stouthearted substance of the old Dutch colonists who had built them.

Across the tracks in the center of a fenced plot overgrown with tall grass, stood the little Chinese temple. The entrance was flanked by two leontine monsters but the building itself was unimpressive. In fact, it was falling to pieces and already resembled a ruin.

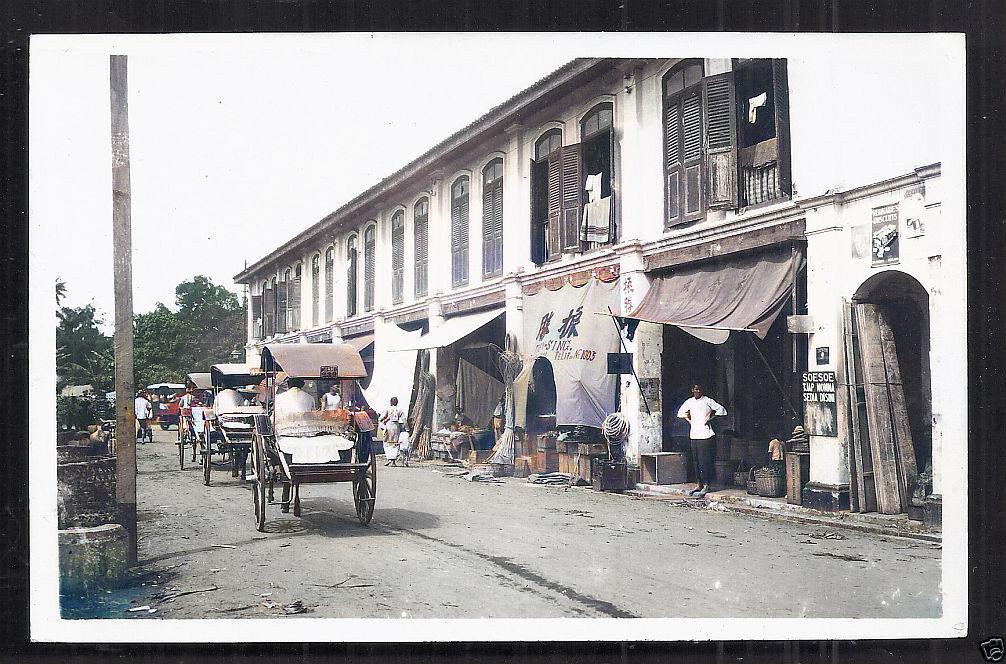

The temple served as the gateway to the Chinese quarter. Everywhere in Medan you encountered Chinese but here they ruled the roost completely. The houses were two-storied stucco affairs, the living quarters located upstairs, the ground floor opening like a windowless store-front directly onto the street. It was within those yawning caverns, closed in by wooden blinds at night, that the Chinese merchants and artisans conducted their operations within full view of all passers-by. The coppersmith’s journeymen, stripped to the waist, were belaboring their metal and setting up a din which I heard from afar. A barber was wielding his machine clippers, a dentist was digging and drilling right under my nose, so to speak, as I passed. Shoemakers, bicycle repair men, merchant sall were performing their routine tasks like actors on an open stage.

The streets and sidewalks of the quarter were teeming with traffic and I was able to make my way along practically unobserved. This was a source of satisfaction to me, considering how strangely self-conscious I felt. A little Chinese girl with shiny, coal-black eyes and two bristling braids was leading her small brother by the hand. Both appeared freshly scrubbed and combed. They were obviously on their way to school, for each was carrying a slate. Privileged characters those, who could afford both time and money for school. Most of the Chinese youngsters had to help in store and workshop and only the tiniest tots were allowed to spend their time at play.

The whole scene was boiling with activity. Customers coming and going, the entire quarter humming like a bee hive. A well-to-do Chinese rolled past in a rickshaw. Perched high above the multitude, he sat with hands folded across his bag-like belly. He was wearing a pith helmet, of course, but his white duck suit was an ill-fitting, washed-out mess. The warning cries of his coolie echoed through the streets as he endeavored on the run to find a way for himself and his Portly Passenger through those swarms of milling natives.

For even if the Chinese were in the majority there, people of all races were flocking to seek the yellow man’s bargains. His incredible frugality, his ant-like diligence, his never-failing capability have rendered him indispensable to the economic life of the entire Indies. Who is to repair your bicycle, take your photograph, build your house from cornerstone to locks, and grapple with all the other tasks of your everyday technical requirement if you cannot send for the nearest Chinese craftsman? Certainly you would not think of calling in a native Malay, the brown man’s taste and talent for such forms of endeavor being strictly limited. As a consequence, urban life in the Indies is conspicuous for its foreign elements, principally its· Chinese. Medan, like so many of its sister cities, is a product, not of the country as a whole, but rather of European governmental control acting upon the economy of Indo-Chinese enterprise.

The signs, with their decorative ideography, tended to enliven the street scene but did little to mask the essential dreariness of the quarter. Close scrutiny revealed the fact that most of the buildings were sadly in need of repairs. The outside stucco work was cracked and crumbling and had begun to fall away in great patches. Whitewash seemed but a memory, roof-tiles lay loosely jumbled, as though after an earthquake, and the blinds of many a shop hung. On the whole, the properties appeared to be victims of let-it-go-at-that indifference. Most of them seemed to cry aloud for the encouraging effect of some green thing growing about them. The naked walls, the filthy, worn-out Pavements dePressed me beyond measure. Add to this the intolerable stench from open sewers, and you will understand why I held my nose and gasped for breath as I stepped across the footplank leading from the street to the shop where a sign above an open workroom announced in English: Chung Kee-Tailor.

Chung himself, wreathed in smiles, came forward to greet me. Rubbing his hands and bowing with Chinese obsequiousness, he bade me welcome. In the rear of that barren, whitewashed room a couple of experienced tailors were treading away like fury on a brace of Singer sewing machines. They offered me barely a passing glance. On the wall appeared the establishment’s sole concession to interior decor: two framed photographs, doubtless family portraits before which Chung Kee daily bowed.

The Chinese are a cleanly race and, despite the filth and stench of the street, the tailor shop was immaculate. Bolts of duck cloth were offered for my inspection. After deciding on some material I could afford, I let Chung take my measurements and set a day for my first fitting. Our entire conversation was in Malay, a grammarless language whose study is mainly vocabulary. The cramming I had done on shipboard had provided me with plenty of words and these, I noted smugly, had met their first test.

The sun was well up in the sky and was already beginning to cast its flaming lances into the street when I responded to Chung Kee’s “Tabeh, Tuan!” and stepped from his door. The shadows were melting away and the heat was puffing its breath into every nook and cranny but, for all that, the traffic was still thick.

The hour was now at hand for Tuan Besar to appear at his office. Seated alone in the rear seats of their private cars driven by Malay chauffeurs, these dignitaries were now Part of the general traffic. The composite Picture of a spotless white duck uniform topped by a tropical helmet would gleam from afar.

In a dense throng the half-naked pigtail men with their yellow, shiny skin swarmed through the sultry stinking, narrow alleys. On either side were stores and workshops. In these small and dirty workshops, glaringly lighted with carbide lamps, naked yellow shoemakers’ or tailors’ assistants squatted in long rows on low stools. Outside the stores sat pot-bellied I

taukehs, sucking repulsively smelling Chinese tobacco from squalling water-pipes. Naked Chinese children were running and playing about in the dust. Wretchedly emaciated dogs snuffed in ·the gutters at the edge of the alley and jumped away yapping when some high-spirited shoemaker’s assistant hit- one of them over the side with his last. In one of the workshops an old gramophone was playing weird, croaking, whining Chinese melodies. The travelling kitchens of the itinerant inn-keepers and those who squatted on the edge of the pavement spread indescribable odours.

Our wheezing ricksha coolie had great difficulty in advancing; Chinamen lounging about blocked his path, wooden slippers clattered in front of him, children were squabbling. Gramophones screeched, and the air was sultry and nauseating

Leave a comment